© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

Famous Expresses - 1

Some English and American “flyers” compared

THREE LONDON & SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAY EXPRESSES AT BATTLEDOWN JUNCTION. From the painting by F. Stafford, presented to the LSW Railwaymen’s Institute, Vauxhall, by the late Dugald Drummond, Mechanical Engineer to the L &SWR.

PROBABLY in no other part of the world is the speeding-

In the chapter “Two Famous Sixty-

In order to secure a fair comparison, it is necessary to take into consideration the nature of the road traversed, the relative size and power of the locomotives employed, the fluctuations in load, and the adverse factor of junctions. The American train is hauled by a very powerful engine of the Atlantic type, the load does not vary very considerably, and the line runs through virtually open country from end to end. On the other hand, the English train is hauled by a relatively light, small machine, the load varies very considerably, and, owing to the North Eastern Railway serving a densely populated territory, liberally provided with railway facilities, numerous junctions serve to hinder the opportunities of making pace. From the grade point of view the English railway has the advantage, since there is only one bank, rising at 1 in 366 for 2½ miles out of the 44, the balance being virtually level.

OILING UP THE NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY'S FAMOUS “FLYER”.

The average load of the North Eastern train is six coaches, representing about 150 tons, though in the summer the train often is called upon to draw nine and ten vehicles, bringing the load up to some 250 tons. It is always hauled by one of the fine North Eastern 4-

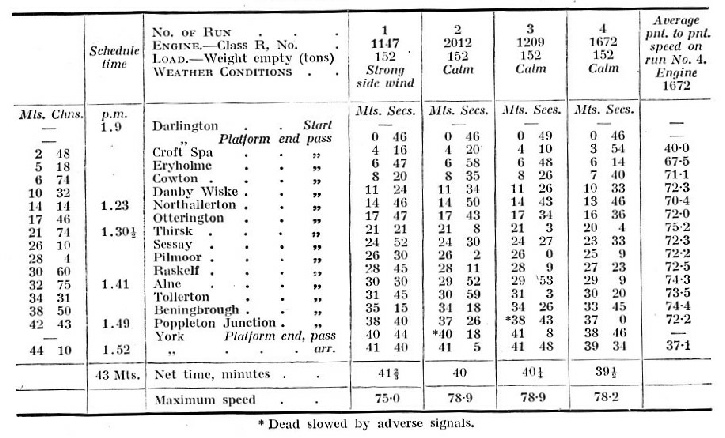

For the purpose of showing what running performances this train can achieve, through the courtesy of Mr. R. J. Purves, of the Signalling Engineering Department, who has shared the accompanying logs, which were run under his own timing. Each of the four runs was made on a Saturday, when the train usually is heavily crowded; in fact, in Run 4 the passengers were standing in the corridors.

LOGS OF THE 12.20 p.m. NEWCASTLE TO SHEFFIELD EXPRESS -

These logs shows the point-

Run 4, with engine 1672, shows a most phenomenal start, and it is doubtful whether a parallel thereto could be found anywhere. From Darlington to Croft the road is level, but this engine got into its stride so quickly that the impression of descending a steep gradient was conveyed, because a velocity of 60 miles an hour was attained within three minutes of starting from rest. Even after passing Croft, and when climbing the bank of 2½ miles length at 1 in 366, the train continued accelerating until, when passing through Eryholme, 69·2 miles an hour was notched. Clearing the bank, 70 miles an hour was exceeded immediately, and maintained over the succeeding 35 miles

of virtually level road until steam was shut off at the second milepost out of York, the 35 miles being covered in 28 minutes 50 seconds, giving an average of 78·2 miles per hour. The maximum speed attained was 78·2, a velocity which even the crack American train would find it difficult to equal.

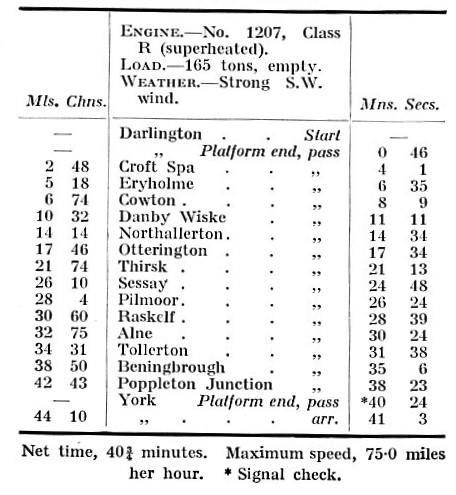

Referring to another log with reference to Class R locomotive No. 1207, shortly after it was fitted with a superheater. This engine was selected by the company to work the “flyer” regularly, the driving crew being changed weekly. On the day of this run the engine was hampered badly by a strong south-

constitutes a remarkably fine piece of work. In this case a speed of 60·8 miles was registered in passing Croft Spa, while 60 miles an hour was maintained at the top of the bank at Eryholme. This run comes out with a maximum speed of 75 miles an hour during the journey, and there is no doubt that had the conditions been as favourable on this trip as on the occasion when locomotive 1672 acquitted herself so finely, the latter’s record would have been lowered.

LOG OF THE 12.20 p.m. NEWCASTLE TO SHEFFIELD EXPRESS AS BETWEEN DARLINGTON AND YORK

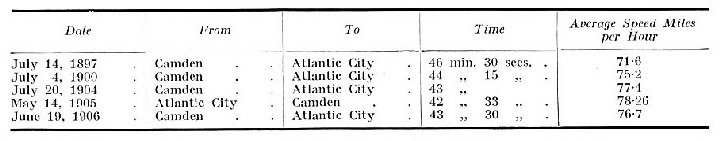

Inasmuch as the comparing of achievements always appeals to those interested in railway running performances, the fastest runs of the American rival between Philadelphia (Camden) and Atlantic City, a distance of 55½ miles, are given below.

Thus it will be realised that, all things considered, the achievements of the North Eastern crack train compare exceedingly favourably with its American rival, and certainly entitle it to the distinction of being the “fastest train in the British Empire”.

TIMINGS OF THE ATLANTIC CITY “FLYER”, 1897-

Turning from the north to the south of England, although the circumstances are somewhat different, some first-

The feature of the Southampton route is the two-

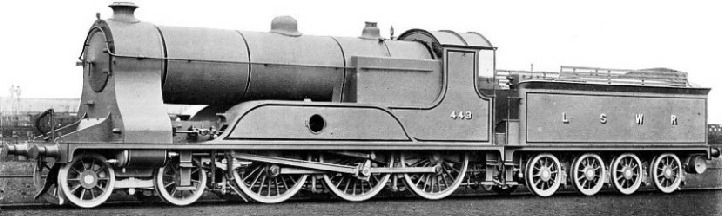

THE LONDON-

In the early years of the first decade of the twentieth century the London and South Western held paramount position in the travelling time between London and Exeter, a distance of 171¾ miles. It was the first company to bring the two points within 210 minutes’ travelling of one another, its competitor requiring an additional five minutes to connect the two points, though the latter route was 22 miles longer. The rival endeavoured to reduce the time handicap, but the competition resulted in the South Western Company clipping fifteen minutes off the timing, making the 171¾ miles in 195 minutes. The run was divided into two non-

THE POWERFUL 4-

When the London and South Western first made a bid for speed, the fastest trains were usually double-

used in the express traffic may not comply with aesthetic considerations, but there is no denying their hauling power and speed.

The “Santa Fe de Luxe”

One of the finest trains in America is the “Santa Fe de luxe” of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe

Railway. The problems facing express working upon this railway are of a peculiarly difficult character, and in the run from Chicago to Los Angeles the train has to overcome no fewer than six mountain ranges where the grades are staggering. After leaving Chicago the line has a practically level run of 240 miles to Fort Madison, the maximum grade westward being 31·68 feet per mile. The 200 miles from Fort Madison to Kansas City have a similar maximum grade, except at one point, where there is a rise of 42·24 feet per mile. Kansas City is at an elevation of 750 feet above the sea, but within the next 640 miles the train has to climb to 7,608 feet, the summit of the first range at Raton. For the last sixteen miles to this summit the train has to struggle against a rise varying from 106 to 185 feet per mile, followed by an immediate descent of 175 feet per mile. Passing Raton, the line drops 1,858 feet, climbs 980 feet, falls again 500 feet, once more struggles to 7,421 feet, descends 500 feet, followed by another ascent of 1,011 feet from an altitude of 6,230 to 7,241 feet at Glorieta, the second summit, these violent fluctuations in level occurring within 200 miles. Then comes another heavy drop of 2,307 feet to Albuquerque in the course of 60 miles, followed immediately by another heavy pull up 2,309 feet in 160 miles to the summit of the Continental Divide. There is a further heavy fall to Winslow at 4,848 feet in the next 160 miles, followed immediately by a stiff ascent to the Arizona Divide at 7,300 feet in the course of 80 miles. Thus four summits have been overcome within a distance of 600 miles.

THE “SANTA FE DE LUXE” MAKING 65 MILES PER HOUR. This weekly train covers the 2,263 miles between Chicago and Los Angeles in 63 hours, giving an average speed for the whole journey of 36 miles per hour.

The railway falls away from an altitude of 7,300 feet at the Arizona Divide to 578 feet at Needles, the 6,665 feet difference in level being overcome in 600 miles. After leaving Needles the line rises 1,930 feet in 40 miles, and drops 1,897 feet in 60 miles to Amboy. Then comes the terrible upward pull to Cajon summit at 3,820 feet altitude, involving a climb of 3,209 feet in about 90 miles. Now ensues a terrific sudden drop of 2,744 feet to San Benardino, followed instantly by a rise of 2,949 feet to Tehatchapi summit, which is about 50 miles by rail from Cajon summit. For 25 miles the rise through the Cajon Pass varies between 116 and 158·4 feet per mile, while there are 25 miles of grade at 116 feet per mile to the Tehatchapi summit.

When the Santa Fe set out to accelerate the train service over the 2,263 miles between Chicago and Los Angeles, it was faced with a very stiff proposition. Yet there was public demand for a crack train between these two cities, and the public was quite prepared to pay for the accommodation. The railway built a special train, one of the most luxurious in the country, and in 1911 inaugurated the Los Angeles Limited, undertaking to complete the journey in 63 hours. This represents an average speed of 36 miles per hour from terminus to terminus. But, seeing that speed over the heavy mountain banks, even when additional motive power is taken on, must fall, it will be seen that upon the more favourable parts of the track velocities of 65 and 70 miles an hour must be attained.

But an average of 36 miles was a decided improvement upon competitive trains between the two points, inasmuch as the “Santa Fe de luxe” completes the journey in five hours less than its nearest rival on the westward run, while coming east the same train shows an advantage of no less than eight hours. For the improved facilities travellers by this train are mulcted an extra £5 over and above the ordinary fare. But they do not grumble. The public has patronised the train so enthusiastically that it is a complete success.

THE ATCHISON, TOPEKA, AND SANTA FE “CALIFORNIA LIMITED” making speed over the heavy grade of 158·4 feet per mile through the cajon pass. To maintain the schedule a powerful “Mountain Mikado” helper locomotive is attached as pilot.

You can read more on “Famous Expresses 2”, “Famous Trains” and “Two Famous Sixty-