© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Kriegslokomotiven

The German State Railway’s Wartime Austerity Locomotives

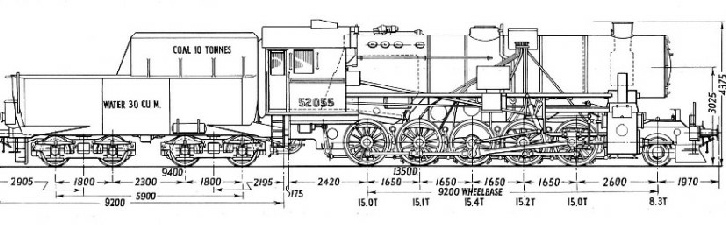

THE STANDARD ARRANGEMENT and principal dimensions of the German lightweight Class 52 2-

WHEN THE NAZIS declared war on the Soviet Union in June 1941, those who said that the Wehrmacht would go through Russia like a knife through butter did not have to wait long to see their prophecy fulfilled. By autumn the German armies were already hundreds of miles into Soviet territory on a 2,000-

Yet it was precisely at that moment, when final victory must have seemed within their grasp, that things began to go wrong. Experts had already warned that the speed and scope of the Russian campaign was straining communications to the limit, but it was only with the onset of winter that the gravity of the situation became clear, as almost overnight the dusty highways of Eastern Europe disintegrated into impassable quagmires of freezing mud.

With road transport virtually at a standstill the Germans had little choice but to use the railways —hitherto neglected as of no particular strategic value, and accordingly in poor shape to cope with the sudden influx of additional traffic. Hastily devised measures which included the conversion of many broad-

With vast troop concentrations already immobilised on the outskirts of Moscow and Leningrad in sub-

Because of the extreme urgency, and to shorten the design stage, both were based on suitable existing prototypes — Class 52 on the already well-

Detail designing of the new machines went on during the spring and early summer of 1942, and without further preamble authority was given on August 5 for the construction of 15,000 locomotives — 7,000 of Class 52 immediately and 8,000 Class 42 starting in 1943. It was, and still is, the biggest order for motive power in the history of railways; and it speaks volumes for the sublime arrogance of the Nazis that they could plan ahead on such a gigantic scale even in the midst of total war. Or was it that they already feared the critical shortage of oil fuels which afterwards became the Achilles heel of the German war machine?

Certainly, by the summer of 1942 time was no longer on the German side, and with hindsight the experts have since agreed that the vital decision on motive power was taken two years too late. In any case the programme was never completed. The continual pressure of allied bombing eventually slowed production almost to standstill, so that by the end of the war in Europe only about half the engines on order had been completed. The respective totals were 6,353 of Class 52 and 843 of Class 42, plus large stocks of component parts which enabled the production of both classes to be resumed later. Even so the huge number of 52s completed in under three years was a remarkable achievement by any standards. It was of enormous importance in sustaining the German war effort, and also explains their familiar presence in so many parts of Europe which won for them the universal sobriquet “Kriegsloks”.

Engine 52.001, the first to be completed, left the Borsig works in Berlin on the evening of September 19, 1942, on a round trip of 4,500km visiting all the locomotive works concerned with their construction. It returned on October 5, after which the class went into general production at 14 factories. In addition to German requirements, 150 were supplied to countries with outstanding orders from German firms in lieu of designs that had been discontinued in the interests of standardisation.

Post-

The main objects in redrafting the Class 50 design into the Class 52 were to reduce the use of imported non-

Class 52 Class 50

Engine weight in working order 84 tonnes 87 tonnes

Tender weight in working order 60 tonnes 60 tonnes

Heating Surface (tubes) 177.5sq m 177.5sq m (1,908sq ft)

Superheater 64.0sq m 64.0sq m (685sq ft)

Grate Area 3.9sq m 3.9sq m (42sq ft)

Cylinders (2) dia x stroke 600 x 660mm 600 x 660mm (23⅝-

Boiler Pressure 16atm 16atm (227lb per sq in)

Indicated horsepower 1,625 1,620

Driving wheel diameter 1,400mm 1,400mm (4 ft 7-

Despite a difference of only three tonnes in overall weight between the two classes, the economy in metal was important, as two tonnes of the saving was in tin and copper. Moreover, although various prototype fittings, such as smoke deflectors, were dispensed with in Class 52, other

features, such as a totally enclosed cab and protective pump covers, had been added.

The tender, while having the same laden weight as that of Class 50, was an entirely new frameless design based on the Vanderbilt pattern. Structurally it was 7.3 tonnes lighter, permitting the coal and water capacity to be increased by 2 and 5.3 tonnes respectively, without exceeding the 15 tonnes maximum axle-

The saving in man hours per locomotive compared with the prototype was 33 per cent, achieved mainly by the simplification of parts and the reduction to a minimum of the machining and processing of components. Predictably, the 52 class proved to be a very capable and reliable locomotive. One useful characteristic was ability to run in either direction with equal facility up to a maximum of 50mph, thus dispensing with the need for turntables. It was also particularly well suited to severe curvature and rough, newly laid track, which it proved able to negotiate without sustaining frame fractures and other serious forms of damage.

Officially, the performance of the 52 class was rated at 1,400 tons at 37.5mph on level track with coal of 12,650 BTU, but as their steaming capacity was on the shy side it was not always achieved. Until the end of 1943 hard coal was usually available, but subsequently it was mixed with 50 per cent soft brown coal (lignite) or briquettes, which increased fuel consumption by 30 to 40 per cent and required the services of two firemen on the footplate for all heavy long-

The reason why no allowance for the use of poor quality fuel was made during the design stage was probably due to the urgency of the project and the confident hope that such an eventuality would not arise. In any case, by 1944 the Germans were in no position to do much about it, and it was not until after the war, and the advent of the Giesl ejector, that a remedy was found which permitted fuel of 9,000 BTU to be burned without any significant loss of power.

By the early part of 1943 the Kriegsloks became available in quantity, and from then on most of them were allocated to the eastern front, where they were urgently needed to replace the older 38-

Thus, although the 52s came too late to help the German forces re-

Even so, their period of wartime service was shortlived; by the end of German resistance in May 1945 the bulk of them were still less than two years old. In fact, taken as a class they spent so little time under the auspices of the Third Reich that their history belongs more to the post-

You can read more on “The Flying Hamburger”, “Germany and Holland” and “Some German Achievements” on this website.