A fight with Nature in the wilds of Alaska

RAILWAYS OF AMERICA - 22

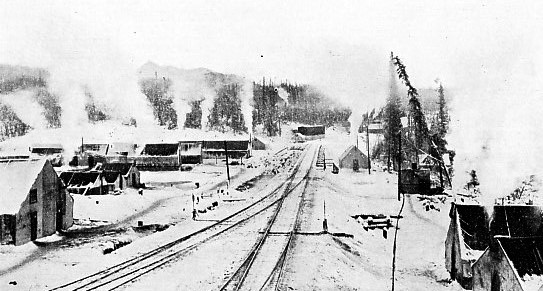

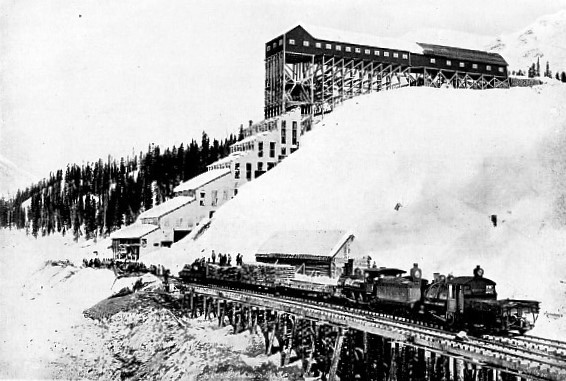

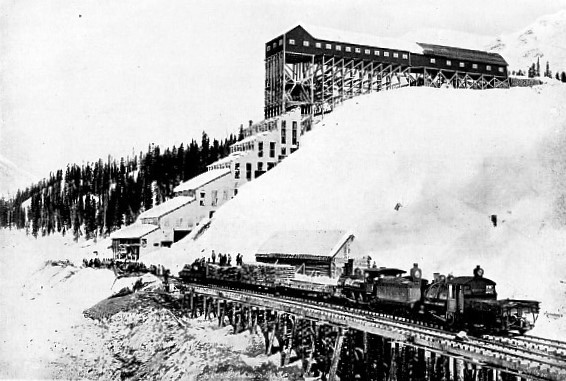

A RAILWAY CONSTRUCTION CAMP on the borders of the Arctic Circle.

WHEN, in 1867, the United States handed over gold to the tune of £1,440,000 to Russia, in return for the half-million odd square miles of towering mountains and yawning valleys known as Alaska, there were plenty of critics who croaked that the bargain was a good one for Russia, but a bad one for “Uncle Sam”. To-day [written in 1913] it would be impossible to find an American who is not wildly enthusiastic over the future of that far northern country. During the forty-five years the land has been under the Stars and Stripes, although it has been practically a closed book, over £70,000,000 have been taken out of it in the form of furs, fish, and minerals, in point of value. The latter easily stands first, having yielded over £32,000,000, mostly in gold, and gathered by the crudest of processes.

Alaska is an enormous treasure-ground, but no idea of its riches was gained until the Klondike was over-run with gold-seekers. Hardy, long-headed prospectors maintained that the mineral finds in the Yukon Territory must continue through the adjacent country to the west, and promptly they started off to scratch the mountain sides and to sift the beds of the rivers and streams. Their perseverance and temerity were rewarded. They returned to civilisation with wonderful stories about the latest Eldorado, and clinched their pictures with convincing specimens of coal, copper, and gold, which were in abundance. There was only one difficulty: the riches were hoarded up in the interior, to penetrate which demanded untiring patience, grim determination, and hard toiling over the mountainous fence running along the coast-line.

The circulation of the stories concerning these “strikes” precipitated a northward rush from the United States. Although only a year previously the momentous stampede to the Klondike had been made, with its harrowing and dismal round of hardship, peril, privation, and disaster in the struggle over the Chilkoot Pass, the Alaskan pioneers were not to be turned from their purpose. They were eager to get rich, and quickly, too. During the months of February, March and April, 1898, it is stated that 3,000 men landed at the obscure port of Valdez, bound for the interior. It was a terrible heart- and back-breaking journey over the ever-upward zig-zagging trail across the ice of the Valdez Glacier to an altitude of 4,800 feet. Many of these gold-fever-stricken fools never had seen a glacier in their life until they caught sight of those of Alaska, which are the largest known to civilisation, and then they were staggered.

But they were so intoxicated with buoyant enthusiasm that they never paused to reflect upon the prospect. They had sleds on which they stowed their outfits, and which they considered adequate to overcome the obstacle. When the “old boys”, already in occupation, told the “tender-feet” that they must carry ropes, firewood or oil-stoves, and other necessaries with which to cook their food and to obtain their water by melting the snow or ice when camped on the glacier, the new arrivals laughed derisively. But those who disregarded the timely advice soon had occasion to repent of their assumed superior knowledge.

It was no easy going over the Valdez Glacier. The river of ice is torn and riven by rifts and chasms in all directions, and the trail wound in and out among these death-traps in the most bewildering manner. Time after time a meandering tramp of three or four miles was required to make an advance of one mile. The unusual spectacle was to be seen of villages of tents pitched at intervals on the glacier where 300 or more men were in evidence. The seething mass of impatient humanity made the distance between two camps a daily instalment of the journey.

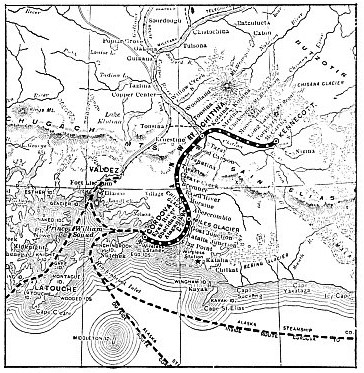

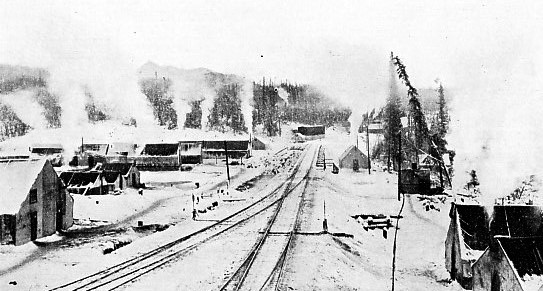

ROUTE MAP OF THE COPPER RIVER AND NORTH WESTERN RAILWAY.

The blinding snowstorms, gales and raw fogs contributed to the miseries and difficulties of those on the mush. A blizzard lasting 120 hours on end is by no means uncommon in these latitudes, while the frequent avalanches, rattling down the slopes, mixed tents, men, horses, and outfits in a wild melee. Movement during the brilliant illumination of the day was impossible, since the snow was then softest and most treacherous and the agony of snow-blindness was encountered. Accordingly, the gold-seekers surged forward during the night under the soft gleam of the Northern Lights, when the thermometer dropped to its lowest daily reading.

Yet all this wearing of sinew and muscle was in vain. The pluck and endurance of the prospectors were mastered by the glacier; cheap transport was impossible. Castles in the air were shattered, and the greater number of the men trekked painfully and wearily back to Valdez. Those who could afford it paid for steamship berths back to Seattle; others less fortunate either stole or worked their passage southwards. A few of the hopelessly stranded lingered behind to found the town of Copper Centre, only to be ravaged by an outbreak of scurvy which decimated their ranks.

A few of the hardy spirits who escaped the attacks of disease tried their luck once more after the winter had passed, and to their dauntless courage the awakening of Alaska really is due. A copper belt was found along the Chitina River, and the richness of the ore was so tempting that at last the interest of financiers became awakened. A small group was formed to work these resources, and thus the opening up of Alaska began in true earnest, as the provision of facilities to gain the mineral district was the first consideration.

An organisation, the Katalla Construction Company, was formed by the alliance of Messrs. J. P. Morgan and the Guggenheims, who control the smelting industry of the United States, to complete a railway into the interior and to found a port upon the coast. It was recognised that the forging of the essential communicating link would bristle with searching difficulties and would cost an enormous amount of money, inasmuch as the Chitina River district lies on the east side of the towering mountain range which runs parallel to and hugs the coastline. Moreover, owing to the numerous spurs running from this great backbone to the water’s edge, where they break off in precipitous cliffs, the natural facilities for handling vessels, in relationship to the route of the line into the interior, are very few and far between. There was only one point where the Saint Elias and Chugach Mountains could be pierced economically: that was the gorge through which the tumultuous Copper River hurries and scurries to the sea. It is not a river; it is merely a headlong rush of water, foaming through canyons, and wandering aimlessly over low-lying nooks in the mountains.

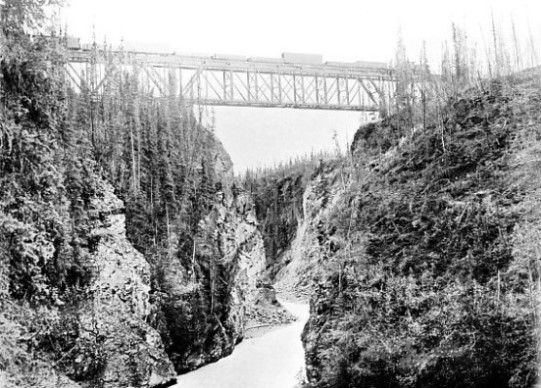

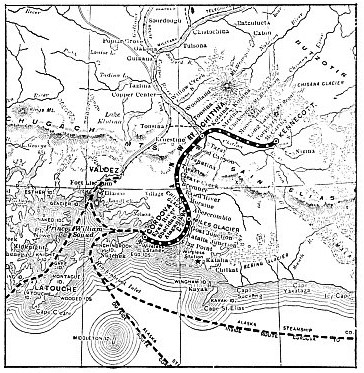

ONE OF THE WOODEN TRESTLE BRIDGES across the Copper River.

The selection of the tide-water terminus was the first question, and the syndicate experienced a lively hunt and dismaying rebuffs in this connection, because the discovery of a suitable harbour proved as elusive as the will-o’-the-wisp. As Valdez had come into such prominence with the gold rush of 1898, the engineers thought it would be an ideal situation for their purpose. A large sum of money was expended in improving the port, when suddenly it was announced that the grade from that point through the mountains would be too heavy. Accordingly Valdez was abandoned. Then it was decided to secure a point at the mouth of the Copper River itself, and as Katalla, on the south side of the estuary, offered every inducement, harbour-building operations were commenced there. A breakwater was thrown out to enclose a large area of water in which ships might unload and load. When £200,000 had been expended it was found impossible to secure a sufficient depth of water, while complete protection could not be secured against the heavy storms experienced along this coast-line. Indeed, one tempest played sad havoc with the works already completed, and in face of the unequal odds Katalla shared the same fate as Valdez.

A third decision brought the terminal on the northern side of the Copper River estuary, and here the American interests received a startling check, which at the time appeared to be more insuperable than the hostility of Nature. While the Katalla Construction Company’s engineers had been scouring the coastline, and probing the mountains for the easiest route for a railway, British enterprise had won. A railway builder, Mr. M. J. Heney, and Mr. E. C. Hawkins, an experienced engineer, with British financial backing, had carried through the White Pass Railway in the face of tremendous odds, and had learned from bitter experience just what railway construction through such heavy country entailed. When the line to the Klondike was completed, the builder and the engineer, supported by the same financial interests, having heard of the Morgan-Guggenheim intentions in Alaska, quietly moved northwards to achieve another conquest. Unostentatiously they ran up and down the Copper and Chitina Rivers, and discovered not only the easiest and cheapest, but also the only practical, location for a railway, as well as an ideal terminus on the seaboard with plenty of deep water, at Eyak Village, near Cordova. The Katalla Construction Company finally seized Cordova for their terminus, and it proved suitable; but when they endeavoured to run up the Copper River they found themselves balked by the rival British interests.

THE ROAD THROUGH THE DISMAL TUNDRA OR MUSKEG.

When the Americans realised the situation seven miles of line were built, and there was every indication that toil would not cease until the Bonanza Mine was gained. The British owners were prompted to push ahead with their work, because they knew only too well that if the American syndicate were determined to own their own railway to the mines — well, they would have to buy out those already in possession. It seemed as if the Americans were doomed to be outwitted by British shrewdness and enterprise, as they had been in connection with the White Pass Railway. A fight was impossible, as the rival was entrenched too firmly. The Morgan-Guggenheim combine accepted the inevitable and offered to buy out the British interests. A deal was effected, the latter securing a tangible hold in the American undertaking. Mr. Hawkins was made vice-president of the Katalla Company, while a new subsidiary concern, the Copper River and North Western Railway, was created, with Mr. Hawkins as general manager and chief engineer, while Mr. Honey was given the contract to build the line.

The railway is of standard gauge, and after it rounds the tongue of land forming the northern shore to the Copper River estuary, picks up the river proper at Flag Point, the waterway being hugged for 104½ miles to Chitina. Then it swings to the east, to follow the Chitina River as far as Kennecott, where the Bonanza Mine is situated.

This railway runs through some of the wildest, most repelling country it is possible to imagine. Forbidding canyons, through which the water thunders savagely, stretches of swamp, toes of glaciers, water-logged alluvium, and mountain shoulders were encountered in turn. At places the fight put up by Nature was of the sternest character, and the engineers were not able to get through with their narrow shelf on which the metals are laid for less than £50,000 per mile. Money had to be poured out at the rate of £15,000 per mile for 25 miles, whiie another section averaged £20,000 per mile. Thousands of pounds literally vanished in smoke, because hundreds of tons of giant powder went up to blast the narrow causeway through the hard rock of the mountain humps. Individual blasts of 15 and 20 tons of explosive were quite common, and when work was in full swing at the point where the going was hardest and heaviest, an army of 1,500 men found employment, driving their way relentlessly forward yard by yard.

In plotting the line, it was decided to keep the gradients down as far as possible. This was a laudable proposal but difficult to fulfil in a land where the forces of Nature have carried out their work in a mad, haphazard manner. It required money: if this were forthcoming the engineer could be trusted to achieve the desired end. But the question of curvature was not solved so easily. The river twists and turns amazingly, and as the route had to follow the waterway, the engineer was not given much scope to straighten out these sharp bends unless he embarked upon a wholesale mountain-moving campaign.

BUILDING THE GREAT STEEL BRIDGE ACROSS THE COPPER RIVER. One of the most expensive bridges in America. In the photograph water is seen flowing over the ice of the frozen river after a sudden thaw.

The labour question was perplexing. Men accustomed to heavy mountain-railway building were difficult to obtain. Down in the Western States railway expansion was exceedingly active, and the demand for workmen was so keen and well paid that labour was not compelled to go northwards to suffer virtual imprisonment, the Arctic blasts, low temperature, and other perils for a few dollars per day. The contractor, as he was working upon a time-limit, at one time required 4,000 men. His appeal was answered by a handful of scores! The rigours of the climate played sad havoc with all but the most hardened and experienced toilers. Many men, after a brief experience, had to abandon their task and return to more congenial climes. The southern European races, although for the most part excellent navvies, could not tolerate a country where the rainfall averages 120 inches per annum, where the thermometer sinks to 60° below zero in winter, where the snowstorms rage for days without ceasing, and where the wind rushes with such velocity as to beat through the thickest clothing as if it were only muslin. Scandinavians were the men most naturally fitted to the task; they are acclimatised to this latitude, and are born workers in rock.

The “muskeg”, or bog-land, was exasperating. In winter, under the wand of King Frost, it becomes as solid as a rock to a depth of some 20 feet; in summer, owing to the power of the sun, it is transformed into a half-set jelly, which, although it will support the weight of a man, sucks down anything heavier. Huge piles were driven into this plastic mass, and the spaces between the legs, which were held together with cross-pieces, were loaded with stone blasted out of the rock cuttings. Fortunately, in Alaska this tundra is not able to thaw out entirely: the heat of the sun cannot penetrate to a depth of more than 10 feet or so. The result is that the bottom of the bog is eternally frozen, so that the piles when driven downwards to a foot or so below the frost mark secured a firm hold.

While the Alaskan summer is delightful, with the temperature hovering about 94° in the shade and the sun shining for nearly twenty out of the twenty-four hours, it brings its own peculiar discomforts.

The flies are an implacable enemy. The muskeg forms an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes, while the little black fly and the caribou-bug are equally vicious. They can only be kept at a distance by “smudges” — smouldering fires of damp leaves emitting dense clouds of smoke — but these are impracticable when navvying. A pungent, oleaginous dressing — “fly dope” — applied to the face and hands secures respite from their attacks until the odour has evaporated, but this is an indifferent makeshift. The toilers only secured relief by encasing their heads in finely meshed muslin nets, resembling flexible meat-safes, while their hands were encased in large gauntlets. At night they were compelled to sleep in mosquito-proof nets.

The summer brought added perils in the form of snow, rock, and land slides. The fierce heat of the sun melts the heavy blankets of snow that clothe the mountain tops, causing large masses to slip. Once set in motion, they never stop until they reach the depths of the gorges below. The rock and land slides were equally fearsome. With a rattle and a roar, as if a gigantic artillery duel were in progress, huge boulders, hillocks of loose debris, trees, and what not come careering down the slopes with terrific fury, setting up tornado-like winds in their train and spreading destruction on every hand. The heavy melting of the snows also contributed to the turbulence of the rivers and creeks, the waters of which rose and fell several feet within a few hours. When the Copper River is swelled by these enormous additions of water, it rushes along with the fury of a mill-race, bearing the gaunt stumps of towering trees on its bosom, and carrying away the soft, friable parts of the banks with the greatest ease, only to pile all in unsightly humps, ridges, and banks at the delta, where the river straggles over a wide area. The engineers, therefore, were compelled to lay their pathway well above the fiercely scouring force of the river, otherwise its life would have been brief.

While the path of the railway for the most part lies along a shelf hewn and torn out of the mountain flanks, which tumble into the river almost with the steepness of a plumb-line, its advance was disputed by another formidable natural obstacle — glaciers. From the banks of the Copper River may be seen some of the largest and most magnificent active ice rivers in the world. Two of these — Miles and Childs Glaciers — come to the water’s edge at a point 40 miles distant from Cordova, and are wonderfully picturesque and impressive. Childs Glacier in particular is enthralling. It rises from the water in a solid scintillating cliff to a height of 300 to 500 feet, while from one end to the other of its prismatic face is a distance of three miles. Throughout the livelong day during the summer the “calving” of icebergs is in progress, and the spectacle is wonderful, as the large detached masses tumble into the water with a roar, sending immense waves rolling across the river and huge columns of spray into the air. To avoid this obstacle the railway swings across the river over a huge bridge.

At one point an unprecedented piece of railway engineering has been consummated. The line runs

along a shelf which has been cut out of the dead end of the stagnant Allen Glacier, where the metals are laid, upon the ice for a distance of five miles. At first sight the situation does not present many of the attributes of a river of ice, inasmuch as the end of the glacier is completely covered with dense scrub and other debris. But when the rock-hogs attacked the section they blew out huge chunks of ice in their blasts laying bare the toe of the glacier. The ice river was plainly discernible alongside the track for two years afterwards. Someday perhaps the Allen Glacier will suddenly return to life and push the railway into the river. Then the engineers will have to throw another bridge across the wide waterway to gain the opposite bank. No apprehensions are entertained on this score at present, however, as the ice river has evidently been quiescent for many score years past.

THE BIG STEEL BRIDGE OVER THE COPPER RIVER BETWEEN MILES AND CHILDS GLACIERS. Childs Glacier, 300 feet in height, is seen in the background; icebergs in the foreground.

While winter brought a relief from the assaults of the flies, and rendered movement somewhat easier by snowshoe and sled over the snow-carpeted ground and frozen waterway, the workmen had to keep on the move and encase themselves in heavy woollen clothing to keep the blood circulating through their veins. When the temperature hovers around 70° below, and the Arctic wind is blowing keenly, the severity of winter’s rule is felt. The Copper River valley is a funnel through the range, and the wind, being forced into a narrow space, tears along with fearful velocity. At times the men could not keep their feet, and swinging heavy hammers, guiding the descent of massive pieces of metal for a bridge, or putting the rails shipshape, whilst endeavouring to maintain one’s balance, is somewhat precarious. Attempts to ease this situation were made by erecting timber screens to act as “breakers”, but the Arctic gale caught hold of these defences and splintered them to matchwood. Now and again a new fall of snow would come sliding down the mountain slopes, heading straight for the constructional forces. There was a shrill cry and a wild scamper to safety until the snow had gone. Then the men returned, and with their shovels diligently toiled to extricate the railway and trucks.

While the location of the line through the rugged narrow canyons, where the engineer had to seize every available foot of ground to receive the metals, was exciting work, it is the bridges which catch the eye, especially those over the Copper and Kuskulana Rivers. Both are great achievements, completed under the most exciting conditions. But in addition there are numerous other erections of this character, wrought in concrete, steel and timber, according to circumstances, with here and there a fine example of wooden trestling.

Bridge-building commenced ere the engineers had got into their stride, and had picked up the mouth of the river. It is an ill-kempt estuary sprawling over the whole width between the two lofty banks, which fall back somewhat at this point. The river, which in the course of its mad rush to the sea collects vast quantities of silt, is forced to disgorge its ill-gotten gains at this point, and accordingly throws it up in dreary banks and ridges, intersected with numerous channels. These flats are the home of millions of wild fowl of all descriptions, and as food is available in plenty, they constitute ideal breeding grounds, the low thick scrub providing excellent protection. As the delta is practically a quagmire for the whole of its width, a large bridge of nine spans, for which over 4,000 tons of steel were required, had to be built to carry the line from bank to bank. At first, however, a timber trestle was thrown across the gap to enable the railway to be pushed forward, the permanent steel bridge being built at leisure.

When the engineers had penetrated about 22 miles up the river, their advance was disputed by the towering ice wall of Miles Glacier on the left bank, while on the right bank loomed Childs Glacier, the bulb ends of these two mighty rivers of ice being almost opposite. A swing across the waterway was imperative. A point about three miles below the glacier was selected for the crossing, and as the river here widens out to form a lake, it was seen that a teasing and tedious piece of work was unavoidable. As construction on the opposite bank could not be held up until the bridge was completed, a ferry service was established on the waterway, whereby materials and men were transferred from bank to bank. By this arrangement the engineers were given plenty of time to reconnoitre the situation and to lay their plans so as to secure complete success.

NOT A CANAL, BUT THE RAILWAY FLOODED. After the rotary snow-plough had passed a glacial stream broke through, and, filling the snow cutting, rendered the line impassable.

As the bridge runs parallel to the face of the ice wall, and about three miles below its foot, the engineers were confronted with a somewhat perplexing problem. The Alaskan glaciers are particularly active, and an advance of 5 feet per day is by no means abnormal. In these circumstances icebergs are calved by the hundred, and while the river is open come sailing down the waterway in a never-ending procession. It is a majestic spectacle for the visitor, but this phenomenon was regarded with misgivings by the bridge-builders. When an iceberg, weighing several hundred tons, is swept along at a speed of eight or ten miles per hour, woe betide any object which it may chance to strike. If this happened to be a bridge pier, well, the handiwork of man would offer a very insignificant resistance and present a sorry sight after the collision.

One whole summer was devoted to observing the “calving” and “flow” of the bergs, the channels they favoured, as well as their varying velocity, size, and behaviour when they were caught up by the scurrying river. Some of the bergs were observed to be of immense dimensions, towering 20 feet and more out of the water, and although their advance was braked, owing to the lower extremities dragging along the river bed, yet they kept going at a steady seven miles an hour. The disintegration of the glacier and the run of the bergs continued incessantly from June 1st to November 1st, when winter descended upon the scene.

The menaces only could be compassed by building a huge bridge of a total length of 1,550 feet, divided into four spans. The problem was the disposition of the piers, but the observations had revealed the presence of two bars in the stream which the bergs skirted, and very seldom fouled. By seizing these sand-bars as the points for the piers, the bridge was divided up into spans of the following length — 450 feet, two of 400 feet, and 300 feet respectively. It was decided that the span over the main channel should be a cantilever, the heavy spans on either side thereof being the anchor arms. A “camel-back” design was adopted for the spans, which, owing to the bridge being placed athwart the river, and thereby being exposed to the full broadside pressure of the hurricane winds, were designed to withstand a pressure of 40 pounds per square foot when loaded, and 60 pounds per square foot unloaded.

By setting the piers on the sand-bars, although the danger from bergs was avoided, another equally serious peril was courted — packing of the ice. In winter the river freezes to a depth of 7 feet, and when the thaw comes there is a wild melee. The ice splinters in all directions, and the floes, caught by the suddenly awakened river, are tossed hither and thither and hurried down stream. But their progress is impeded by other floes which have not started on their ride to the sea, and these decline to be driven prematurely. Consequently the skeltering ice behind piles upon that in front, forming big jambs. As the river thus becomes blocked, the level of the water behind the pack rises, setting up an enormous pressure. The packing of the ice is accentuated by the existence of any obstacle in the waterway, such as one of these bridge piers would offer, and it would be difficult to contrive a support which would effectively resist being pushed over bodily. To remove all possibility of this calamity, “ice-resisters” were built around the piers, and these, strengthened by iron rails weighing 56 lb. per yard, which were used in constructional work, offer a complete defence against the push of the ice. Foiled, the broken ice grates and grinds itself to pieces in impotent rage against the defences, until finally it is swung to one side and carried down stream.

Work was commenced in the winter, when the river, at its lowest, was rendered quiescent by its icy armour. The men toiled laboriously in a temperature 70° below zero, bringing up the heavy caisson machinery, facing the knife-edged Arctic blasts, and struggling desperately against blinding blizzards. Nearly five months were occupied in this preliminary task, and the sleds were kept going continuously. Delays were frequent. Now and again there would be a galling hold-up owing to a snow slide hitting the railway and burying it to a depth of 30 feet or so, hindering the movement of the trains until the obstruction was shovelled away.

Labour was crowded on during the reign of the ice-king, but it was exasperatingly slow cutting holes in the ice to permit the heavy wooden piles that constituted the falsework for the anchor spans to be driven home. Saws were useless, with ice feet thick, so steam jets were played upon it, the pile slipping gradually downwards as the hole was melted.

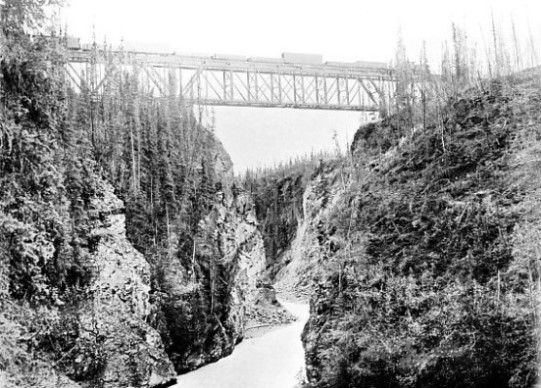

THE KUSKULANA BRIDGE. The river thunders through the gorge 175 feet below the line.

When work was at its height, during the winter of 1910, operations were thrown all sixes and sevens. The weather, with its characteristic eccentricity, broke, a warm spell setting in at the very time when the country should have been firmly gripped by frost. The thaw was accompanied by heavy, driving rain. The armour of the river became submerged by some 2 feet with freezing slush, and this superimposed weight caused the ice, as the thaw progressed, to sink to a lower level. Childs Glacier awoke and burst into unwonted activity, by slipping forward at the rate of some 10 feet per day.

This unexpected development precipitated an alarming situation. By the constriction of the channel the water was backed up, and the enormous pressure thus exerted upon the under face of the icy covering burst it in all directions. The falsework, which happened to be in the way of the movement, suffered heavily, the massive piles being forced out of position and the cross-bracing torn from its fastenings.

The thaw lasted about a fortnight, when winter again settled down to its humdrum condition; but it broke up earlier than was expected. The bridge-builders were caught at a disadvantage. The ice began to heave under the swelling volume of water beneath, and in so doing lifted the falsework of the first two shore spans on the south side of the river. As some of the steel had been set, disaster seemed imminent. The men stopped erecting and concentrated their energies to alleviating the ice pressure with steam jets and chisels welded to the end of short lengths of 1-inch piping. As the steam caused the ice to release its hold upon the timber the men plied their chisels for all they were worth, clearing the hole so as to permit the piles to sink back again into their beds. Large gangs toiled laboriously night and day in this unequal conflict, and at times the situation became thrilling. There would be a creak and groan ! The ice would be seen to lift. The workmen hurriedly dragged their tools to the spot and played the screeching live steam upon the “heave”, so as to bring the steelwork which had been disturbed above back to its place. Sometimes they wore successful; at others they were not. In the latter event the “bridge-flies” swarmed the superstructure and corrected the movement by the aid of jacks, wedges, and blocks resting beneath the girders.

While this work was in full swing, and the men were congratulating themselves that they had frustrated the effect of the ice, Miles Glacier started moving. The advance of an ice ram over 50 miles long by 3 miles wide, and some 300 to 500 feet high, into a neck of water, is bound to precipitate some unexpected contretemps. In this case it caused the water in the river to burst through its icy bonds, the ice being smashed into huge fragments, which were caught up and hurled against the falsework. The hammering was so heavy that a part of the timbering was detached and swung round, when it collapsed. The men fought like demons day and night incessantly throughout a solid week, and just as they were commencing to gain the upper hand, after a certain amount of damage had been wrought, Childs Glacier entered the combat and bombarded the work with icebergs, which it threw off one after the other with startling rapidity. These monsters, becoming entangled with the piled ice, imposed tremendous pressure upon the bridge. The structure appeared to be doomed : the workers were helpless, and the engineers were prepared for a gigantic smash, although they never ceased their efforts to avoid catastrophe. Just as suddenly the situation cleared: the river opened up, and carried away the pack-ice and bergs in a wild rush. The bridge was saved. The damage wrought was repaired quickly, and before the next winter set in the structure was completed after around £100,000 had been spent.

The Kuskulana Bridge is of quite a different character. When the engineers swung at right angles from the Copper River to push westwards along the Chitina River valley to gain Kennecott, their path came to the brink of a deep ravine — a crack in the earth’s crust with precipitous rock walls 175 feet deep and 190 feet wide, through which tears the Kuskulana River. After completing the surveys the engineer decided to span the gap with a massive deck truss-bridge, 525 feet long, divided into three spans, the longest of which, of 225 feet, immediately over the gorge, was to be erected on the cantilever principle.

The engineering party entrusted with this task left Cordova on April 1st — an auspicious date — 1910, intending to travel by train to the railhead, which was rapidly approaching the gorge. They carried all their requirements, so that work could be commenced the instant they arrived at the site. But the train had gone only 22 miles when there was a breakdown. The ine was buried beneath a heavy snow-slide. The rotary plough had been bucking into the obstacle, but the revolving scoop had struck something it was not designed to handle and was thrown out of action. The track was 2 feet under water, a glacial stream having broken into the canal-like cut made by the plough. This had frozen almost solid, so that the train was stalled hopelessly, even if the snowplough were repaired. Sooner than suffer delay, the party tumbled out of the caboose, donned their snow-shoes, loaded up their small sleds, and toiled over the snow and ice for a distance of nearly 80 miles. Hard on their heels came a labouring gang of fifteen men, who dragged their equipment on sleds over the whole 100 miles of arduous, zig-zagging, back-breaking trail between Miles Glacier and the Kuskulana Gorge. The constructional material itself had been brought up previously by small steamers, which at great risk penetrated almost to the bridge site.

As the bridge was to be built simultaneously from both sides of the ravine, the initial task was to establish a means of conveying the material across the chasm. For this purpose a cableway was erected. A narrow suspension bridge also was thrown across the gulch near the site to enable the workmen to pass from side to side.

The main span is supported at either end upon a steel tower, for which deep pits had to be sunk to receive the concrete foundations. This was painfully tedious work. The tundra was frozen as hard as the rock near by. The warm sun playing upon the muskeg thawed the surface to a depth of 6 inches or so. This was removed within the area required, and a fresh frozen surface exposed to the sun. When this had thawed out it was excavated in turn, and a further section allowed to melt, this process being continued until rock was reached. Progress was very slow, as three days had to be allowed to permit the uncovered frozen surface to thaw out to the depth of the spit of a spade. When the rock was reached, it was found to be split in all directions by frost, and accordingly the foundations had to be taken down 10 feet more than had been anticipated.

While this work was in progress the timber falsework for the shore spans was pushed forward, and by the time the winter came round everything was ready for placing the steel in position. Two immense travellers were set up, as the central section was to be built upon the overhang principle. As the railway had reached the gorge by this time, the material was brought to the brink, and the cable-way was kept going hard, transporting 540 tons of steel-work, while one traveller and four steam engines for hoisting purposes were swung across the ravine.

The arrangements for supplying and distributing the power to the various working positions demanded considerable ingenuity. Owing to the depth of the gorge, the water for steam raising purposes could not be drawn from the Kuskulana River, all supplies in this connection being brought in by train. The water was stored in a tank which was fitted with steam pipes to protect it from frost. As the men on the opposite side of the gorge required water and compressed air, a water-pipe, flanked on either side by live steam pipes, thickly and tightly bound in hay, was laid across the footbridge from the main power station. Although hay is an excellent insulator, it scarcely suffices for a temperature ranging at anything between 30° above and 60° below zero, so that delays frequently occurred from the water-pipe freezing.

The erection of the steel-work commenced on November 8th, 1910, by which time the permanent constructional camp had been moved from Miles Glacier to Kuskulana upon the railhead reaching the gorge. The anchor spans were completed very quickly, when 50 tons of rails were packed on the shore extremity of each to act as counterweights during the building of the cantilever span. The heavy travellers were moved outwards, and the material was brought out to them over a temporary track laid upon the lower deck of the bridge. Once the engineers got well started work went forward merrily. The only serious handicap was the shortness of the Alaskan winter day, there being only about three hours between sunrise and sunset in December. The travellers crept towards one another through the air until they met over the centre of the gorge. Then the mass of steel was manipulated so as to bring the ends in line and to admit the insertion of the last panel to connect the two arms. This delicate operation was successfully consummated with the thermometer registering 40° below zero, the travellers were dismounted, and on January 12th, 1911, the first train moved across the structure. The Kuskulana Gorge was bridged within nine months of the engineers’ arrival upon the spot, while the 525 feet length of steel forming the structure was set in position within two months — a remarkable achievement under the peculiar and arduous conditions prevailing.

While the Flag Point, Copper River, and Kuskulana bridges constitute the outstanding examples of this form of engineering upon the Copper River and North Western Railway, there are 311 small timber trestles. After the Kuskulana Gorge was conquered, the railway advanced to Kennecott, the inland terminus, 195½ miles from Cordova, the metals being carried to the doors of the Bonanza Copper Mine. By the time the last rail of the Copper River and North Western Railway had been laid some £3,500,000 had been spent.

THE END OF THE TASK : laying the metals at the Bonanza Copper Mine.

You can read more on “Defying Death Valley”, “Floods, Fire and Earthquake” and “North American Railroads” on this website.

You can read more on the “White Pass & Yukon Railway” in Wonders of World Engineering