THE MAGIC OF MODERN SIGNALS - 6

One of the most marvellous signalling installations in the world

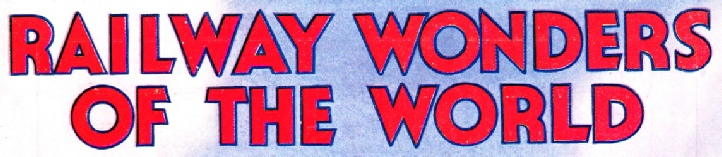

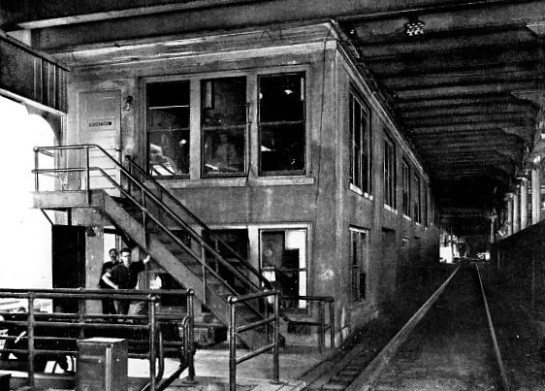

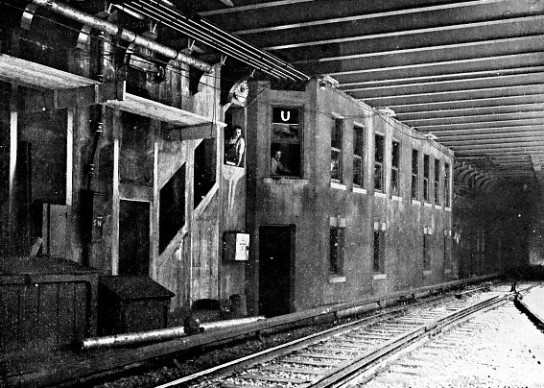

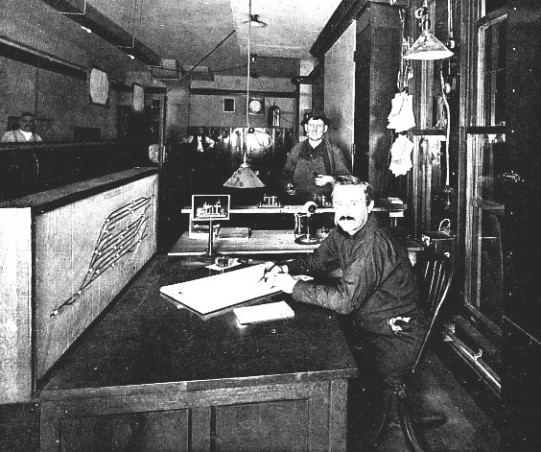

EXTERIOR OF THE CABIN CONTAINING THE 360-LEVER MACHINE controlling all train movements to and from the upper level.

UNTIL the Pennsylvania Railroad laid tube lines under the Hudson River so as to carry its metals from the New Jersey shore into New York City, the only trunk system which had its terminus in the capital of the Empire State was the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. This strategical advantage was secured by entering the city from the north, thereby avoiding the wide, busy waterways which wash the projecting spit of rock known as Manhattan Island.

The builders of this railway plotted their line and terminus facilities for their day; they gave no thought to the exigencies of the future. Three times the Grand Central station, as this terminus is called, has had to be built in order to keep pace with the growth of traffic. The present structure was completed in 1912, and to-day ranks as one of the largest terminals in the world. When this work was taken in hand it became necessary to increase the number of roads so as to accommodate the traffic. Land being costly, they could not be laid upon the surface, as in the previous station; nor could they all be disposed upon one level, except at a prohibitive outlay. Accordingly it was decided to distribute the sets of rails upon two levels, in order to meet the terminal situation most effectively. The upper level, which is 34 feet below the street, carries twenty-nine tracks, while the lower level, 55 feet beneath the public thoroughfares, has twenty-two roads. The whole of these fifty-one tracks are provided for the convenience of passengers, mail and baggage. In addition, there are sixty-two other pairs of rails for the storage of electric locomotives and trains. Previously the trains had to be backed out of the station, and hauled a distance of five miles to Mott Haven Junction yards, where sidings were provided for their accommodation. Such a necessity not only represented a heavy aggregate of unremunerative haulage, but also served to congest traffic, inasmuch as the whole of the business has to pass in and out of New York over four roads — two up and two down. This bottleneck affected the capacity of the terminus very severely, so that by the time the new works were taken in hand not another train could be squeezed into the daily service.

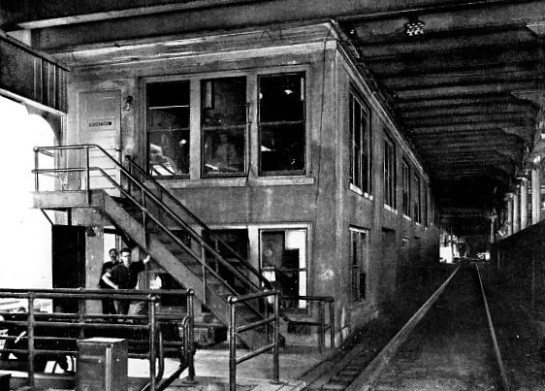

EXTERIOR OF ONE OF THE UNDERGROUND INTERLOCKING STATIONS. Above this cabin on the street level is a 12-floor skyscraper.

By providing the terminal station with platforms at two different depths below the street level, the railway solved an abstruse problem very completely. The upper level is roofed over and covered with streets and huge buildings. Altogether there are 79 acres of sidings and lines provided beneath the imposing hotels, boarding-houses, offices and stately thoroughfares surrounding the Grand Central station. As may be realised, owing to this system, the lines are completely hemmed in, especially those on the lower level, which are flanked on either side by massive steel columns supporting, not only the tracks of the upper level, but also the various buildings above which vary from eight to twenty-three stories in height.

Under such conditions the task of laying out a complete signalling system so as to guard the 113 different roads was intricate and complex, while the situation and construction of the interlocking stations was even more complicated, inasmuch as the conditions rendered it impossible to see the trains arriving or departing from the main line connections.

The solution of the signalling problem forms one of the most outstanding features of the Grand Central station, while, undoubtedly, it constitutes one of the most marvellous installations among the railways of the world. The all-electric system was adopted as being that which would meet all requirements most completely and efficiently, and this is the largest lay-out in the world to be operated in this manner. Moreover, the interlocking station on the lower level is one of the largest which ever has been built, as it carries 400 levers, each of which operates a point or a signal. Altogether, there are five interlocking stations manipulating 238 sets of points and crossings, and 570 signals, to control the 1,200 train movements which are made during every twenty-four hours.

In order to grasp the full significance of the signalling arrangements it is necessary to gain some idea of the disposition of the tracks between the bottleneck and the station. All the various lines ramifying in all directions converge into the two up and two down roads at a point about 5 miles outside the terminus. These four tracks run partly through tunnel and over elevated structures for about 3½ miles. At this point they spread out like a double fan to form the upper and lower levels respectively. The first-named handles the whole of the long-distance traffic, while the last-named

is devoted to the suburban and local business. At this point the four roads are resolved into ten tracks, four connecting with the lower, and six with the upper, level, and here is the first, or A, interlocking station. About three-quarters of a mile nearer the terminus on the lower level is the B interlocking station, which contains the 400 levers. This station controls all the movements on the lower level, since here the four tracks are multiplied into twenty-two roads. Above this box, on the upper level, is the C cabin, which controls all the movements on the upper level over the passenger, mail, and baggage tracks. About 150 feet beyond C and on the same level is the fourth, or D cabin, whereby all the storage trains are handled, while about a quarter of a mile beyond signalling-box B, on the lower level, is the fifth, or E, interlocking station.

The local trains, instead of coming to dead ends as in the ordinary terminus, swing round a big oval loop, so that, after discharging their passengers, they can, if required, pass round to the storage yard until their next turn of duty arrives. The consequence is that there is no congestion in the station; the bottleneck is left free for the handling of remunerative traffic.

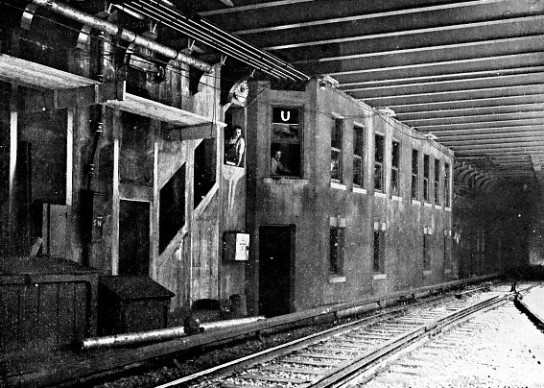

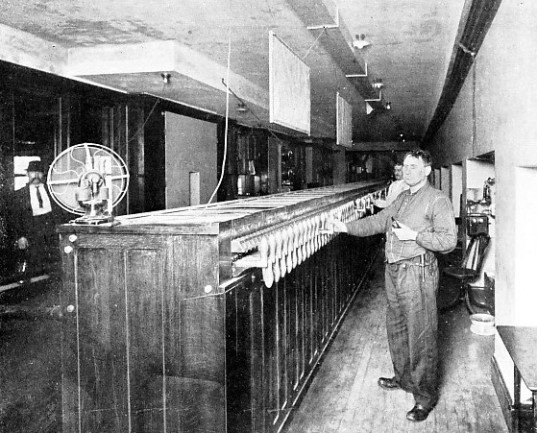

THE INTERIOR OF THE LOWER LEVEL INTERLOCKING STATION, SHOWING LEVER FRAME. This machine, 55 feet underground, contains 400 levers, and the roads which it controls cover 23 acres of ground. The lever-men merely pull the levers called out by the director.

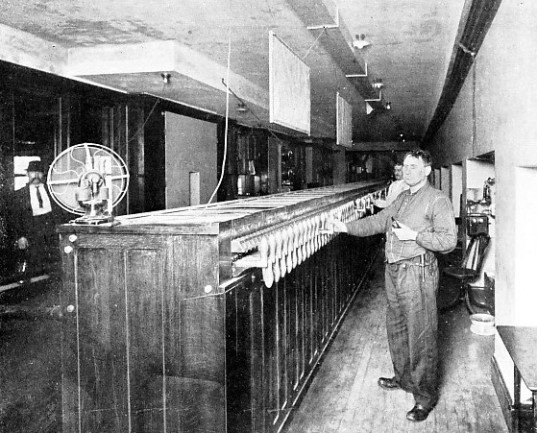

As the whole of the cabins are placed underground, and the range of vision is limited very severely, a signalling system differing from that generally practised had to be adopted. In each cabin there is a director or general manager of the train or interlocking movements. He has nothing to do with the handling of the levers. His sole duty is to receive and to pass on the trains. His desk is provided with a telephone and telegraph, while in front of him are mounted diagrams showing all the roads, points, crossings, station platforms and station tracks under his jurisdiction. Facing him is a chart, on the ground-glass face of which is indicated a facsimile of the tracks. Within the case, and behind the ground-glass, are small electric lights, indicating all the points and crossings. As a train passes over a set of points the corresponding light on the chart is extinguished, and is not relighted until the train has passed over the crossing on to the succeeding one. Thus the director, by glancing at his chart, can detect instantly the precise position of the trains upon the roads under his control. The points and signals are interlocked, so that no error on the part of the operator can set a signal or points in a conflicting manner. Both must agree, thereby assuring the safety of the train. The electric lights on the chart are controlled automatically by the train itself through relays operated by alternating current track circuits.

The ordinary type of semaphore signal is utilised, and at danger occupies the normal horizontal position. When the controlling lever in the cabin is moved, the small electric motor whereby the semaphore is actuated moves the arm upward to indicate “line clear”. When the lever is pushed back, the semaphore drops by gravity to the danger position. This arrangement has the additional advantage that, should any failure occur in the electric system, the arm must fall to the danger position, notwithstanding that the line may be clear.

The signal-operating system is entirely in the hands of the director. Notification of an incoming train is given first by telegraph from the mouth of the bottleneck, 5 miles distant. The director of tower A prepares to receive it, and he warns the director of box B or C, according to whether it is for the upper or for the lower level, of its approach. We will suppose that the train is for the lower level. The director of cabin B, although apprised of the approach of the train, does not know on which of the six tracks the director at A will turn it. Seeing that the train is travelling probably at 30 miles an hour, the intimation must be of the briefest and quickest character. There is no time for telegraphing. When the director at A has decided the road for the train he presses a small electric button on his desk. Instantly a light on the track chart in box B lights up, indicating the track along which the train is coming. The director of the latter immediately presses a similar button which communicates to the director at A that he, the director at 15, has received and understands the signal.

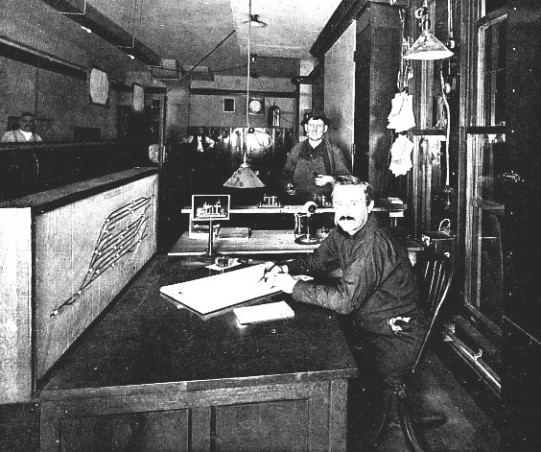

THE SIGNALLING DIRECTOR OR GENERAL MANAGER OF THE BOX, 55 FEET BELOW THE

STREET LEVEL. Showing telegraph and telephone, together with the illuminated track diagram. He calls out the numbers of the levers that are to be moved.

An additional signal also is given to the director in B box, from a point 1½ miles distant from the terminus, by the train itself, through the automatically operating track circuit devices.

To carry the train through his territory the director at B box sets his road. He calls out a number, or numbers, corresponding to the lever, or levers, which he desires to be moved to carry the train over certain tracks. The “lever-men”, as the operators are called, at once move the levers to set the points and signals, a small electric light showing above those levers which are moved. These men have nothing to do but to move the levers indicated by the director. He is the pulse of the cabin: the lever-men merely pace up and down before the “piano box”, as they call the frame, moving the levers at the director’s bidding. As the director receives notification of a train, he records it upon the official form on his desk, which is a permanent record of the movements of a train through the section, and this is filed by the department. Thus, should an accident occur from any cause, it is not a difficult matter to fix the responsibility.

The director’s duty appears somewhat simple at first sight, but when the number of tracks under his control are borne in mind, together with the fact that possibly twenty trains are moving in both directions simultaneously through his territory, it will be seen that he must maintain a clear head and concentrate his mind upon his work. A momentary lapse, the calling out of the wrong number — and then a smash. He is guided in his work entirely by the track lights and telegraphic signals which come to and pass from him.

Another duty has to be performed by the director in box A, which, as mentioned previously, is the first in the chain. Directly he has decided upon which track to turn the incoming train, his assistant, by the aid of the telautograph, communicates to an official on the station the information at which platform such-and-such a train will arrive. This station official, being in charge of the bulletin board, receives the written order upon the machine before him. He tears off the intimation, and his assistant then chalks up the platform number on the bulletin board. Another official speaks the same news into a transmitter, and it is proclaimed from a number of electric machines scattered throughout the station, for the guidance of those who have come to meet the train.

Outgoing trains are dispatched in an equally simple manner. The tower director of the box immediately outside the station works according to the time schedule. He tells the lever-men to set so-and-so signals and points at the minute a train is scheduled to leave, and by communicating with the boxes beyond him gets a clear track to the bottleneck. No sign of the train is seen. The director merely knows that train number so-and-so is due to leave at a certain time, and clears the road for it. Should anything occur to delay the departure of the train, intimation of this fact is given by telephone to the director of the station signal cabin. Special trains are handled in a similar manner from cabin to cabin.

The system is complete in its thoroughness and safety. The fact that the cabin directors are given three distinct notifications of an incoming train — first, from a point 5 miles away by cabin A; secondly, from a point 1½ miles distant, automatically by the train itself; and thirdly, by the electric light system from director to director — conduces to as smooth, steady and safe operation in semi-darkness, 55 feet below the street, as upon the surface with a clear view of the roads.

You can read more on “The Magic of Modern Signals”, “Railway Signalling” and “Seen From the Train” on this website.