© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

| Advertisements |

| Articles by Cecil J Allen |

| Binding |

| Cookie Policy |

| Covers |

| Donate |

| FAQs |

| Illustrations |

| More on Railway Wonders |

| Other Series |

| Privacy & Terms of Use |

| List of Illustrations |

| Locomotive Illustrations |

| Carriage Illustrations |

| Wagon Illustrations |

| Part 1 |

| Part 2 |

| Part 3 |

| Part 4 |

| Part 5 |

| Part 6 |

| Part 7 |

| Part 8 |

| Part 9 |

| Part 10 |

| Part 11 |

| Part 12 |

| Part 13 |

| Part 14 |

| Part 15 |

| Part 16 |

| Part 17 |

| Part 18 |

| Part 19 |

| Part 20 |

| Part 21 |

| Part 22 |

| Part 23 |

| Part 24 |

| Editorial - Part 1 |

| Editorial - Part 2 |

| Editorial - Part 3 |

| Editorial - Part 4 |

| Editorial - Part 5 |

| Editorial - Part 6 |

| Editorial - Part 7 |

| Editorial - Part 8 |

| Editorial - Part 9 |

| Editorial - Part 10 |

| Editorial - Part 11 |

| Editorial - Part 12 |

| Editorial - Part 13 |

| Editorial - Part 14 |

| Editorial - Part 15 |

| Editorial - Part 16 |

| Editorial - Part 17 |

| Editorial - Part 18 |

| Editorial - Part 19 |

| Editorial - Part 20 |

| Editorial - Part 21 |

| Editorial - Part 22 |

| Editorial - Part 23 |

| Editorial - Part 24 |

| Part 25 |

| Part 26 |

| Part 27 |

| Part 28 |

| Part 29 |

| Part 30 |

| Part 31 |

| Part 32 |

| Part 33 |

| Part 34 |

| Part 35 |

| Part 36 |

| Part 37 |

| Part 38 |

| Part 39 |

| Part 40 |

| Part 41 |

| Part 42 |

| Part 43 |

| Part 44 |

| Part 45 |

| Part 46 |

| Part 47 |

| Part 48 |

| Part 49 |

| Part 50 |

The “Limited Mails” of Ireland

A Famous Train of the Great Northern Railway (Ireland)

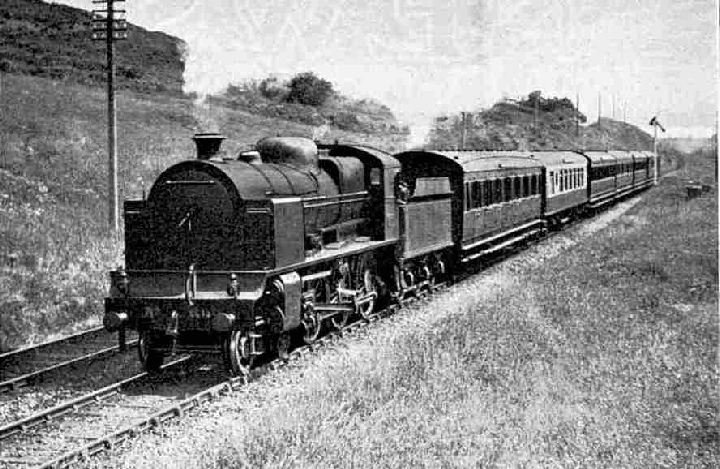

Great Northern Railway (Ireland) 4-

LAST time the “Irish Mail” carried us from London to the Anglesey coast at Holyhead, and the intervening weeks have doubtless proved sufficient for us to pick a fine day and brave the terrors of the Irish Sea on the way across to what was once “Kingstown”, but is now, in the Erse of the Emerald Isle, “Dun Laoghaire”. As I told you last previously, the name of the Irish port need not frighten you; say “Dun Lairy”, and you will be understood at once. Dun Laoghaire is almost a suburb of Dublin, being only six miles from the heart of the Irish capital. It is finely situated on the south-

The pier at Dun Laoghaire, on which stands the Pier Station, stretches well out to sea, and on it we find the trains waiting to carry through passengers to all parts of Ireland. There are the brown varnished teak coaches of the Great Northern Railway, destined northward for Belfast; the blue coaches of the one-

All three through portions just mentioned are to go forward from Dublin by “Limited Mail” trains. The Great Northern portion is usually worked in separately, but the Galway and Cork sections travel together, all of them leaving just after 6 o’clock in the morning, directly after the arrival of the night steamer from Holyhead. The first thing that we notice about the stock is that it is of an external appearance and internal comfort quite equal to the best to be found in England. The second thing that catches our eye, probably, is that three passenger classes are still provided in Ireland, second class still surviving, as it does on the Continent of Europe. There is no sign of restaurant car accommodation, but we shall not have long to wait; restaurant cars will be found on each of the “Limited Mails” to which our through coaches will be attached at the Dublin terminal stations, and we may be sure of an admirable breakfast when the time comes. The third thing the expert eye will not fail to detect is that the gauge of the tracks is wider than that to which we are accustomed; actually it is 5 ft 3-

The short journey of six miles into the Westland Row Station of the old Dublin and South Eastern Railway is the first break, and we then pass by the “City of Dublin Junction” line on through Tara Street and the centre of Dublin, across the Liffey, and into Amiens Street Station, which adjoins the Amiens Street terminus of the Great Northern Railway. Here the Belfast coaches are attached to the Belfast “Limited Mail”, which is booked to start at 6.40 a.m. and to reach Belfast in the excellent time of 2½ hours for the 112½ miles, with four intermediate stops. The Galway and Cork coaches travel on from Amiens Street round the tortuous course of the old Midland Great Western line, alongside the Royal Canal, as far as Glasnevin Junction, where they separate, the former to be worked into Broadstone Terminus, reversing at Liffey Junction, and the latter into Kingsbridge, reversing at Island Bridge Junction, for the outgoing “Limited Mails” at 7.10 a.m. and 7.0 a.m. respectively. The former, which is the slowest of the three, takes 3 hrs. 40 min. to cover the 126½ miles from Dublin to Galway, while the latter is due in Cork, 165½ miles distant, at 10.55 a.m.

As the best locomotive running is generally performed on the up journeys, we will make for England, instead of getting farther away from home, and we must therefore imagine ourselves at the outward end of the “Limited Mail” journeys, ready to begin the journey back to Dublin. The rolling stock makes the double journey daily. Obviously we cannot be in two trains at once, and so we must take the necessary trips consecutively.

GNR (Ireland) 4-

For the first trip, therefore, we present ourselves at the Great Victoria Street terminus of the Great Northern Railway in Belfast soon after five o’clock in the evening; our southbound journey is to commence at 5.30 p.m. The train is of no great weight. On the rear end we notice a slip coach destined for the seaside resort of Warrenpoint, on the coast of County Down, to be slipped at Goraghwood; then follow a large brake and a “tri-

We make the acquaintance of the first of these “sprints” immediately on leaving Belfast. It is 25 miles from here to Porta-

The next non-

Getting smartly away from Portadown at 6.5 p.m. we shall touch 60 miles per hour, probably, before the Scarva slack, and shall pass that station, eight miles, in about 11 minutes. The slight dip before Portadown should produce a rather higher maximum, probably 65, and we shall then set out in earnest to climb. In the early stages of the ascent, fortunately, we say goodbye to the Warrenpoint coach, which is slipped at Goraghwood, the engine being thereby relieved of 30 tons or so. Goraghwood Junction, 15¾ miles, is passed in about 20 minutes, or slightly less. As we mount over the high viaduct at Bessbrook, the centre of whose 18 arches is 140 ft above the valley, we shall be surprised to find the speed dropping but little, if at all, below 40 miles per hour. The climbing of the fine Great Northern superheated 4-

Amiens Street Station, Dublin. This station has three platforms and covers 8,398 sq. yards, roofed. Architecturally it might be in almost any part of the Empire.

Much of the descent from Adavoyle to Dundalk is at between 1 in 100 and 125, or thereabouts, and the line is well laid out for high speed. For myself, I shall never forget my last trip down to Dublin on the footplate of this very express, when in the driving mist and impenetrable darkness of an October evening, with the engine rolling and surging as though she were a monster alive, we most assuredly touched 80 miles an hour down past “Mount Pleasant” -

The lengthy wait at Dundalk is in curious contrast to the high speed that has just preceded it, but time has to be allowed for the Irish Free State customs officials to come and interview you, and it is to be hoped that they will find no dutiable articles concealed in your baggage, or the wait may be longer still! It is quite likely that the engine will be changed here also, a Dublin engine replacing the Belfast engine for the remainder of the journey.

After no less than 13 minutes’ standing, we leave Dundalk at 6.58 p.m. For the next 22½ miles to Drogheda, with their sharp undulations, the allowance is 27 minutes, the booked speed being therefore 50 miles per hour exactly. It should also be mentioned that we have attached at Dundalk a couple of corridor coaches through from Londonderry via Enniskillen and Clones, making up the total load to eight coaches, weighing about 265 tons.

We find the observance of the booking from Dundalk to Drogheda presents but little difficulty, however. There is a steep rise at 1 in 160 for 1½ miles out of Dundalk, followed by falling and then level grades to Castlebellingham, on which we get up to 65 miles an hour or so; then comes Dunleer bank, with its five miles up at 1 in 198, to the summit at mile-

Drogheda we reach at 7.25 and leave at 7.28 p.m. For the final 31¾ miles of gentle ups-

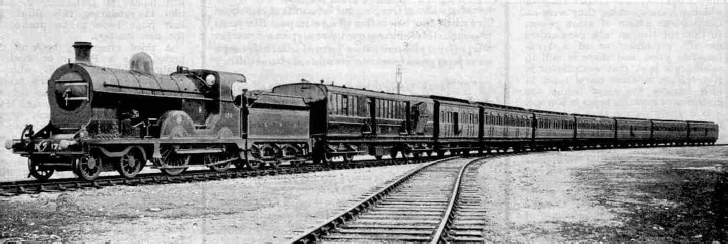

The great viaduct across the River Boyne at Drogheda. This fine bridge was built by Barton in 1854-

Our arrival is therefore at 8.5 p.m, 2 hrs. 35 min. after leaving Belfast, and as 21 minutes of this total has been spent in stops, the actual running time of 2 hrs. 14 min. for the 112½ miles represents an average travelling speed of just over 50 miles an hour for the whole distance -

This express makes its exit from Cork at four o’clock in the afternoon. At one time the train started from Queenstown, or “Cobh” as it is now known, but the start is now made from the Glanmire Road Station at Cork, and a terrifically hard exit it is, too. Right from the start, up past Kilbarry to Rathpeacon, the line rises for 3½ miles at 1 in 70 and then 60 -

It was the old Great Southern and Western Railway that introduced the first 4-

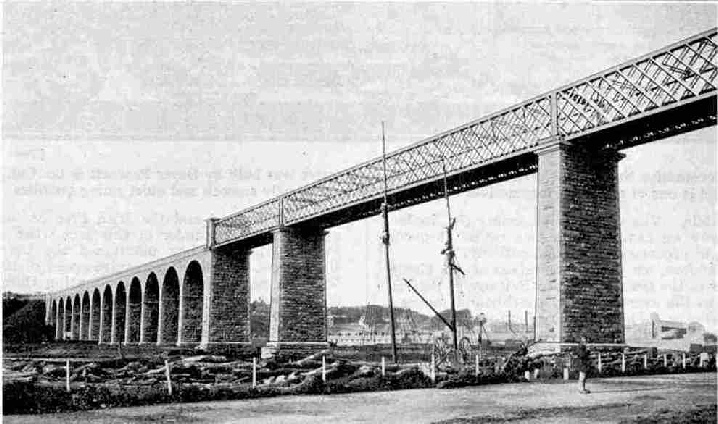

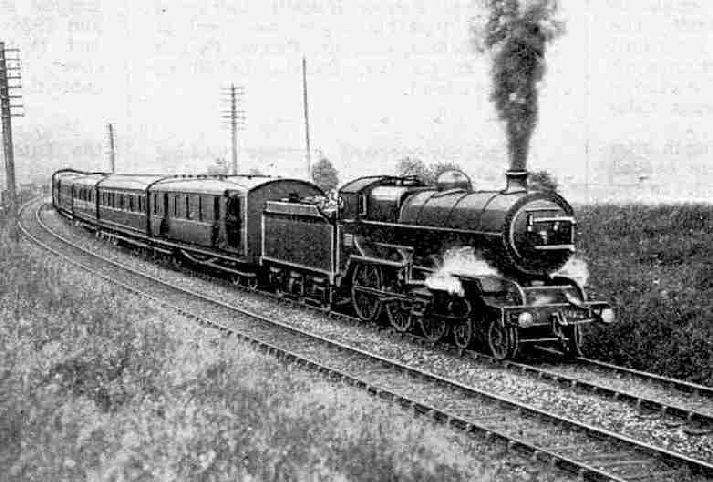

Down Dublin-

Just before running into Mallow we pass over a high viaduct spanning the valley of the River Blackwater. In the Irish troubles of some years ago the original Mallow Viaduct suffered heavily, as it was blown up. A complete breach was thus made in the Great Southern and Western main line, but this gap has now been bridged in a more substantial manner than before, steel replacing the previous masonry. Important connect-

Killarney line to the westward, and the Fermoy and Waterford direction to the east. Four minutes are allowed for this purpose and we get away at 4.30 p.m.

Out of Mallow our locomotive has another bad start, though far from being as formidable as that out of Cork. The rise in this case is for four miles at 1 in 151, to a siding rejoicing in the singular name of Twopothouse. To pass the summit at the 140 milepost, 4½ miles from Mallow start, we may expect to take at least eight minutes, but after that the gradients are mostly with the engine for the next 16 miles, on past Buttevant and Charleville, over which we may expect to average 60 miles an hour or slightly over. From the 124 to the 112 mile-

For the 37¼ miles from Mallow to Limerick Junction the booked time is 45 minutes, but we must make a start-

The 12.30 p.m. Cork-

We reach Limerick Junction, where, as its name implies, the connection comes in from Limerick as well as a connection from Tipperary, at 5.23, and get away at 5.28 p.m. Gentle ups-

Dublin is now the next stop ahead. We are 51 miles distant and, reaching Maryborough at 6.37 and leaving at 6.42, we have 58 minutes left in which to complete the distance, at an average speed of 52.7 m.p.h. From Maryborough we have an excellent downhill start of 1½ miles at 1 in 170, and, indeed, grades generally falling for some 11½ miles in all. We swing through Portarlington, 9¼ miles, in 11 or 12 minutes, and hurry up the four miles at 1 in 180 past Cherryville Junction into Kildare, without the speed falling much below 50 m.p.h. Kildare, 20¾ miles, is passed in 24 minutes at most. The flat plain of the Curragh, so extensively used for military purposes, appears on the right, backed up in the distance by the mountains of Wicklow, to which we draw gradually nearer as we approach Dublin.

All the difficulties of the journey are over, and for the final 27½ miles nothing but falling grades lie ahead. This final schedule, indeed, proves a useful “recovery” margin for time lost earlier in the journey. So we pass Newbridge, Sallins, Straffan, Lucan and Clondalkin; the descent steepens past Clondalkin, the final four miles -

Up English Mail with four-

You can read more on “The Irish Mail”, “Ireland’s Railway Systems”, and “The Ulster Express” on this website.