© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

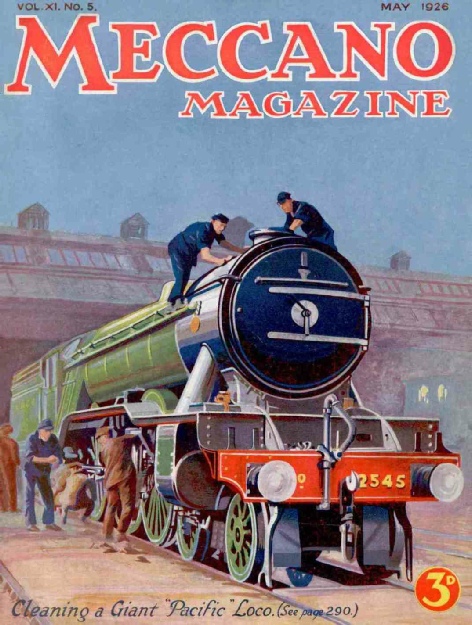

Cleaning a Giant Locomotive

The “Flying Scotsman’s” Four Hours’ Toilet

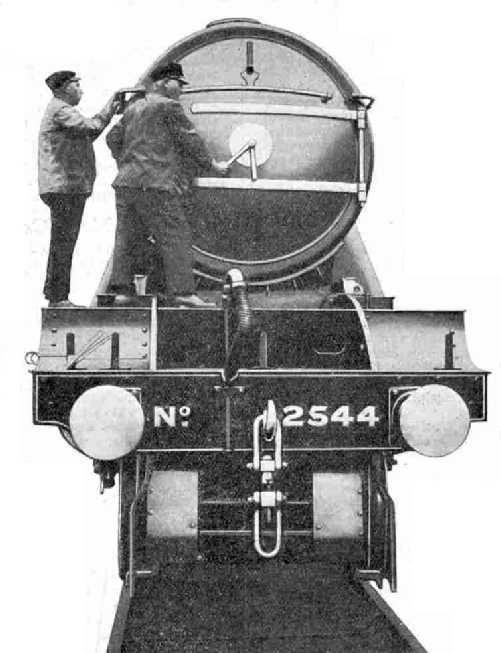

The Driver screws home the fastener of the smoke-

WE all generally think of such fine locomotives as the “Flying Scotsman”, “The Centenary” and other famous members of the LNER “Pacifics” only as speeding between King’s Cross and Edinburgh. We picture them in our mind’s eye hauling trains of enormous length, and being turned round at their destination to start off on the return journey without loss of time.

There is another side to the picture, however, and this is the “toilet” of these giant locomotives -

It is always interesting to visit the King’s Cross Depot, for here some of the “Pacifics” are housed after their return from Scotland. A scene of great activity prevails. Engines are to be seen almost everywhere, some coming in, others going out. The difference between those coming off and those going on duty is as remarkable as, and quite equal to, the difference between workmen going to their work and workmen after the day’s toil.

Some of the engines crawling about the yard, just off duty after racing to King’s Cross from York or Leeds, seem so tired as to be almost falling asleep. They pause only to report themselves at the yard foreman’s office, and whistling a sleepy “good-

In these depots the monster “Pacifics” are very submissive creatures. The “Flying Scotsman” generally seen hissing and snorting with ill-

Over four hours’ preparation by a host of workmen is required to get the “Flying Scotsman” ready for his race to the north. In the giant locomotive’s toilet, and in the attention necessary to get the best possible effect.

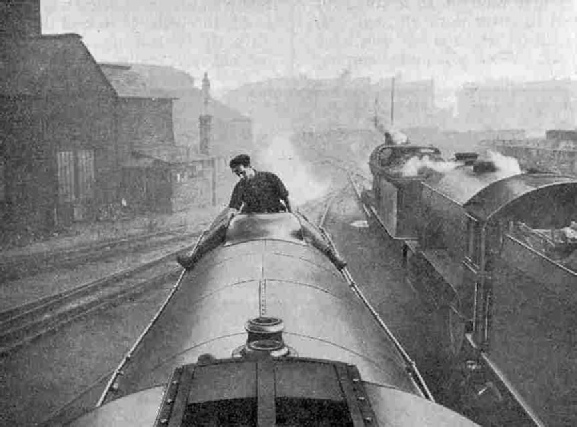

The loco first receives attention from boiler-

In addition to the regular routine, as outlined above, the boiler must be thoroughly cleaned every 2½ days. Barrow loads of scale (or fur something like that found in the ordinary household kettle) are removed. There are 3,800 ft of internal pipes on a “Pacific” and soot and scale quickly collect, considerably reducing the power and also causing a greater consumption of coal per mile than is the case when the pipes are clean.

At King’s Cross the cleaning of the pipes is done by an ingenious washing-

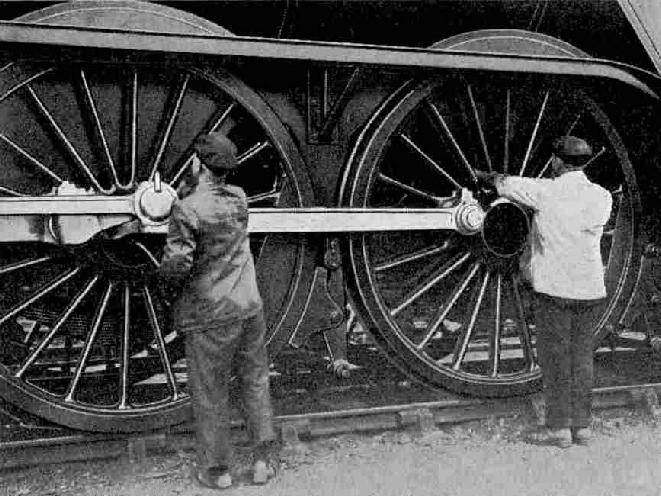

The oiling of these hard-

The oil is delivered in bulk to the Locomotive Depot by contract. There it is stored in large tanks, being drawn off and carefully measured as required, each driver receiving a certain ration according to his day’s run.

Cleaning the outside of the boiler of the “Flying Scotsman”.

On the LNER passenger engines the consumption of lubricating oil for axle boxes works out at about 5 pints to every 100 miles. The consumption of lubricating oil for the cylinders is approximately 1¾ pints for every 100 miles.

In the early days of railways when there was considerably more play in the working parts, cotton waste and sacking soaked in oil were often used to assist in lubrication. It was often necessary for the oil-

The task of the driver of the present day in the matter of lubrication is very different from that of the drivers of the earliest engines, such as “Locomotion No. 1”. Although automatic lubricators relieve him of a good deal of anxiety with regard to oiling, it continues to be necessary for every working part to constantly be examined in order to ensure steady running.

Climbing round the frame while the engine is in motion has, of course, now been done away with -

The modern driver still carries a handful of waste but this is used to remove surplus oil. At the end of the shift, the waste is collected with other waste rags and sent to the oil rag laundries. Here centrifugal oil extractors, working on the principle of the steam turbine, reduce the viscosity of the oil. A mixture, which consists principally of oil and matter, is thrown out and carried through pipes into tanks. Approximately 50% of the oil is, extracted by this first process. Should by any chance a drop of oil escape the centrifugal action of the machine and remain in the cloth, it will then have to face a solution of caustic soda and boiling water.

It is surprising to learn that every year the LNER oil rag laundries save 40,000 gallons of valuable oil in this manner! The reclaimed liquid is not wasted but is placed in catch-

Although the cleaning of locomotives may appear to be a dirty and decidedly unromantic occupation, yet it is from the ranks of cleaners that the first-

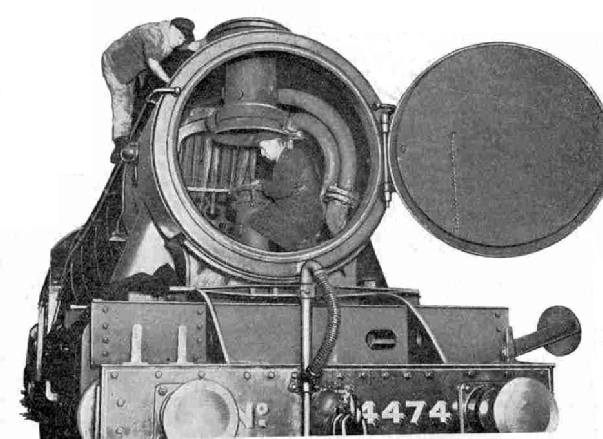

Cleaning the inside of the smoke-

In a large engine shed it is obviously necessary to lay down strict regul-

Once inside the shed the loco is not immediately left to its own devices, but the cylinder cocks must be opened, the hand brakes must be put on hard, the regulator shut and the reversing ever put out of gear. Cleaners are expressly forbidden to move engines in steam, and this can only be done by a driver, or by a fireman instructed and accompanied by a driver, or by the shed foreman, shed shunter or other specially authorised men.

Without regulations of this kind accidents in engine sheds undoubtedly would occur very frequently, but as it is, mishaps are comparatively rare and when they do occur it is almost always as the result of neglect of some rule.

The engine shed bears the same relation to the locomotive as the stable to the horse or the garage to the motor car. Roughly speaking engine sheds are of two types, “straight road”, having several parallel roads passing through the building, or “turn-

The actual sequence of engine shed operations varies in different places but as a rule the loco, having arrived at the shed, is taken charge of by an authorised man and the driver and fireman book off duty. The loco is taken towards the coal stage pit to be filled up in its turn and during the waiting period the smoke-

All locos are apt to develop slight defects. Whenever a driver becomes aware that any part of his engine is not working as it should he makes a note of the fact and during its stay in the shed the engine is taken in hand by fitters, boiler smiths, etc, who have been informed of the defect and promptly proceed to remove it. In addition, all locos go through more extensive examinations at stated intervals, For instance, smoke-

The locomotive superintendent at King’s Cross Depot has 90 engines to look after, and they require each day 600 tons of coal and thousands of gallons of water.

“I wouldn’t mind if they all thrived on it,” he told the writer recently, “but like most human beings they suffer now and then from indigestion! No. 4444 over there came home stuffed-

“But the new arrivals, such as the “Flying Scotsman”, surely don’t need much attention?” I asked.

“Don’t they though!” replied the superintendent. “I’d like to tell you that it takes a loco about three months to get into its stride. Look at 2736 in the comer there. She was new only 10 weeks ago and has been a real handful ever since.”

“What about your ‘oldest inhabitants?’” I asked. “Oh! they don’t give us much trouble. They require very little attention on the whole, but after they have knocked off 90,000 miles or so we give them a thorough overhaul. They’re just going to start on one over there.”

Cleaning and oiling the Giant’s Wheels.

I walked over to the place indicated and watched whilst mechanics penetrated the inner recesses of the smoke-

No giant scales are necessary for this. Instead the work is done by a wonderfully sensitive hydraulic jack, to which is attached an indicator dial.

Placing this compact instrument in a square pit alongside the line, the giant monster of the rail, now steamless and without power, was slowly pushed back towards the waiting lifter until one of the main driving wheels was directly opposite the weigher. “A bit more,” shouted the foreman, and the pushing tank loco strained again to push the inert engine an inch or two further.

“Stop!”

The wheel was directly opposite the weigher, and with a quick movement of a handle the giant was made to lift its wheel as a bear would lift its paw. A workman quickly passed a steel rod between the wheel and the rail to make sure that it was clear.

“Nineteen tons. Next wheel!” shouted the foreman. The tanker came again into action and the operation was repeated. Each wheel was weighed in turn, the total making up the exact weight of the engine as a whole -

Weighing each wheel of a locomotive separately is a valuable guide to the railwaymen, for if the weight is not distributed correctly on the individual wheels the engine will “ride badly” and lose time, or in extreme cases even become derailed.

Cleaning a giant “Pacific” locomotive.

You can read more on

on this website.