© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

The Breakdown Train

How the road is cleared after accidents on the railway

TWO 70-

DESPITE unremitting care and the manifold precautions that are adopted to render railway travelling secure, accidents will happen. This inevitable corollary to movement over the steel highway has been responsible in turn for the creation of a special force, maintained to deal with such contingencies. This is the “breakdown gang”, or, as it is called in some countries, picturesquely if not so appropriately, the “wrecking crew”.

A collision or serious derailment throws the working of a railway all sixes and sevens. The streams of traffic sent flowing with marvellous precision are obstructed, and congestion and disorganisation become complete. The public, notoriously fickle and prone to grumble whenever its own convenience or interests are affected, murmurs against delays, and anathematises a system very vigorously if a mishap is permitted to block movement for a very long time, ignoring the fact that massive, powerful locomotives and heavy coaches or wagons which have capsized or piled-

The railway manager, who receives the full brunt of public obloquy, fortunately is fully alive to the capriciousness of his patrons. So the order runs: “Clear the line with all speed; never mind how; but clear it!” In Great Britain, where double tracking is the rule and not the exception, the full significance of this fiat may not be so apparent, since often it is possible to maintain communication by working the traffic in both directions over a single line; or possibly it can be diverted so that

the delay is not very appreciable. But in those countries where transportation depends upon a single track, the tangle is disastrous, because both streams of traffic are held up completely. Then the full significance of the clearing order becomes revealed very emphatically. The chaotic mass of twisted steel and splintered timber is thrown to one side or cleared right away with frenzied speed, and with very little consideration of salvage.

THE POWER OF THE MODERN WRECKING CRANE. Swinging a locomotive.

The “breakdown gang” is the emergency phase of railway life. The train engaged in this service is kept intact in its siding ready to answer a call at any hour of the day or night. Every tool — saws, hammers, hatchets, jacks, crow-

Nowadays the task of the wrecking crew is heroic indeed, owing to the increased weights and dimensions of locomotives and rolling-

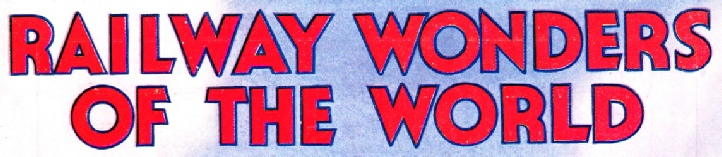

THE WRECKING CRANE AT WORK. Clearing the steel highway. Accidents will happen in spite of the most eleaborate precautions. In order to restore communication in the minimum of time, wonderful and powerful cranes capable of slinging a locomotive weighing 150 tons have been designed.

Therefore, in order to be able to comply with the clearing order, the implements used by the breakdown gang must be of unusual design and power. Indeed, the designing of such equipment has become a highly specialised branch of railway engineering. It was not so many years ago that a small crane of 15 tons capacity proved completely adequate for wrecking operations, but to-

This particular firm has made the wrecking crane one of its special studies, with the result that it is able to meet all requirements with the foregoing monster, or will supply a small implement able to lift only 5 tons or so. But it is the heavier type of crane which arouses the greatest interest, inasmuch as the design of such an implement within the limits of railway working bristles with many peculiar difficulties. In these Industrial Works’ machines all technical questions have been answered in a highly successful manner. So far as the land of their origin is concerned, the demand for cranes of this character, owing to the dimensions and weights of the locomotives now in vogue, tends towards a crane varying in capacity from 60 to 120 tons, with perhaps an enhanced request for those ranging between 60 and 75 tons. Such lifting powers are sufficient to meet all ordinary demands, as cranes up to this rating are quite capable of coping with the average Pullman car, and the box type of wagon, representing 60 tons in loaded condition. Consequently it is the crane able to lift from 60 to 75 tons which is most generally seen. In view of the fact that, in the case of a big accident, the average wrecking train is likely to include at least two such cranes, it is quite feasible to handle a locomotive running up to 130 tons in weight.

HOW THE TRACK IS CLEARED WITH FRENZIED HASTE. An Industrial Works 70-

These cranes are imposing, substantial creations with massive frames of iron and steel. The framework varies from 24 feet 1½ inches in length by 9 feet 6 inches in width, in the case of the 60-

The engines are double; those for the 50-

The very character of the work of the railway wrecking crew demands quick operation, and in the designing of the above machines this salient factor has not been overlooked. In the majority of cases the implement is called upon to handle loads far below the rated capacity. Consequently, ease and dispatch in working are essential features. At the same time the crane must be able to lift its maximum load with equal ease and celerity when the occasion demands. These machines likewise meet this consideration very completely. They are able to hoist the heaviest rated load at the rate of 10 to 15 feet per minute, which, as experience has shown, is adequate for ordinary purposes. Slewing is equally rapid, the 120-

As may be supposed, these cranes are of immense weight. The 60-

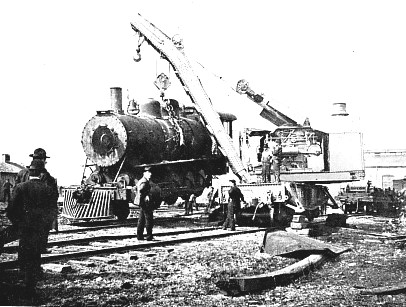

THE MOST POWERFUL WRECKING CRANE YET BUILT. This appliance, designed by the Industrial Works, is able to lift 150 short tons at 17 feet radius.

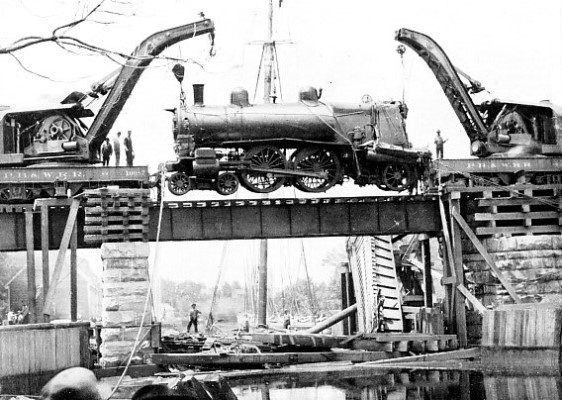

At times the wrecking crews upon the railways of North America are called upon to perform almost superhuman work. On one occasion cranes of this type removed the wreck of a train which had jumped the rails through fouling an obstruction, and had plunged into a river 30 feet below. The result was a terrifying pile of huge box-

The “haul-

On another occasion a passenger train had come to grief by tumbling through a burnt-

out of recognition. The boiler had been crushed in and torn off the frame. But within a few hours its remains were cleared out of the rift, and were piled up on trucks ready for removal to the scrap heap.

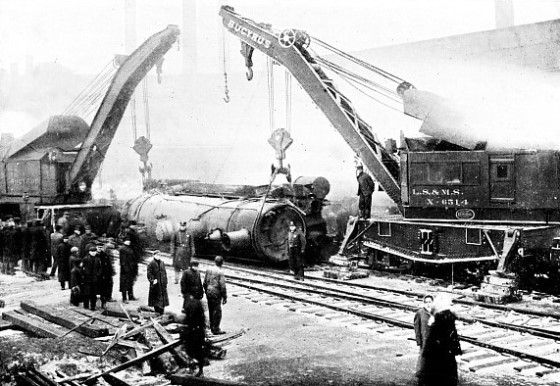

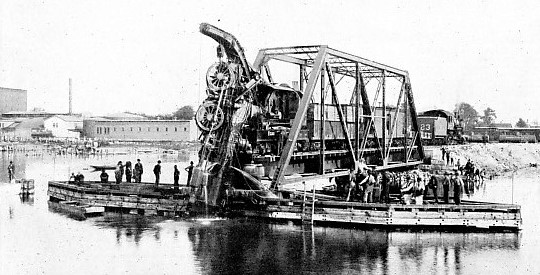

THE TRIUMPH OF THE MODERN WRECKING CRANE. A locomotive which had tumbled through an open drawbridge being lifted out bodily.

But possibly the most impressive illustration of the power of the modern wrecking crane was in the reclamation of a big Mikado scaling a round 100 tons. The engine had been derailed, and had tumbled over on its side, breaking its couplings and throwing its tender athwart the track. The breakdown crane was brought up, and under its own steam — the majority of these cranes are able to propel themselves at about 4 miles an hour, so as to move up to the most favourable points of attack — it crawled towards the tender, which had been wrenched free. In the course of a few minutes this part of the locomotive was whisked out of the way. Then slings were passed

under the locomotive, and it was lifted into the air clear of the track. The crane backed out of the way with its load, to permit the traffic, which had been held up, to pass over the repaired permanent way. At night, in the glare of powerful flare lamps, the crew set themselves to the task of restoring the locomotive to its normal upright position on the rails — a job which was by no means easy. Then the breakdown train was re-

Although a crane of 150-

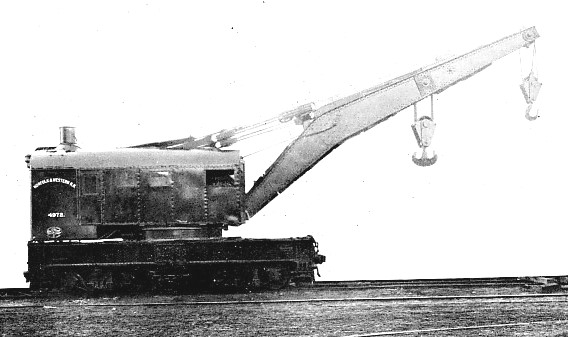

AN INDUSTRIAL WORKS' BREAKDOWN CRANE lifting a wagon body and its load to

afford access to the wheel truck.

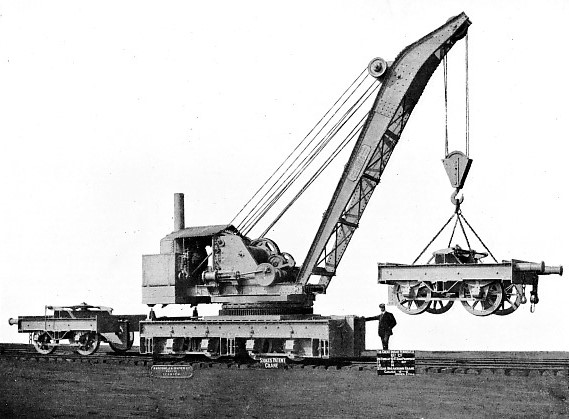

Under these circumstances it is believed generally that the crane of the future will follow quite different lines. In this connection the Stokes articulated crane offers a very complete solution of the problem. This machine has been invented by Mr. Wilfred Stokes, the Managing Director of the Ipswich engineering firm of Ransomes and Rapier, Limited. The scope of this patent is the temporary increase of the wheel-

A NASTY SMASH: the locomotive fell through an open drawbridge on to the deck of a vessel which happened to be passing at the moment: the latter was sunk by the impact.

When the bogies are detached they can be lifted out of the way by the crane itself — slings are provided for this purpose — and can be deposited either on another track or elsewhere until required. The relieving girders are carried by the bogies in such a way as to be moved easily, either vertically or horizontally, so as to facilitate the insertion or withdrawal of the connecting pin. Thus coupling up or relieving only occupies from three to four minutes.

One of the first cranes built upon this principle was for the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, wherein the weight supported by each axle is 16¼ tons when the bogies are removed, and only 10¼ tons per axle when the bogies are attached for travelling. The wheel-

THE STOKES ARTICULATED CRANE, BUILT BY MESSRS. RANSOMES AND RAPIER, LIMITED, at their Ipswich works for the Great Indian Peninsula Railway. Showing how the relieving bogies can be detached and slung clear of the road to allow the crane to be brought up closer to its work.

This articulated wrecking crane, of 5 feet 6 inch gauge, is able to lift 20 tons at a radius of 19 feet. In working order the weight of the crane alone is about 65 tons; complete with bogies approximately 78 tons.

Although designed essentially for wrecking purposes, the duties of these powerful machines are by no means confined to such operations. They constitute a handy tool to the railway engineer when bridges have to be rebuilt, while they are also exceedingly useful for handling heavy loads in the construction shops and yards. For instance, a defect in one of the wheels of a loaded high-

THE LOCOMOTIVE LIFTED FROM THE RIVER and being replaced upon a temporary

track by the wrecking cranes.

Read more on “Accidents and the Breakdown Train”, “Railway Accidents” and “The Railways Daily Work” on this website.