Modern Travel in an Ancient Setting

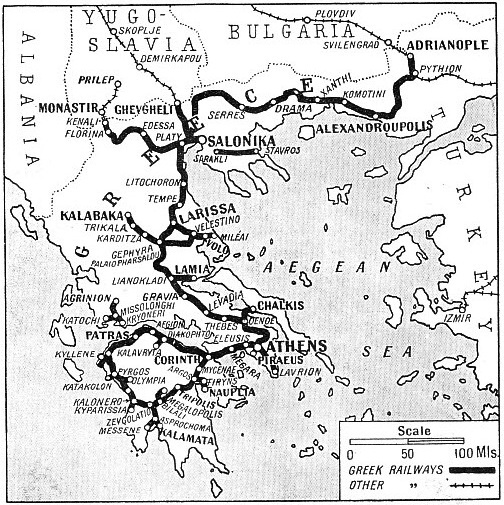

RAILWAYS OF EUROPE - 20

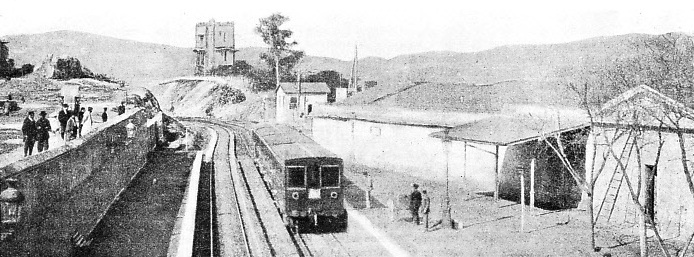

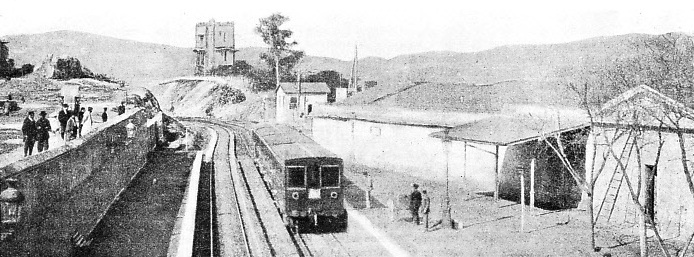

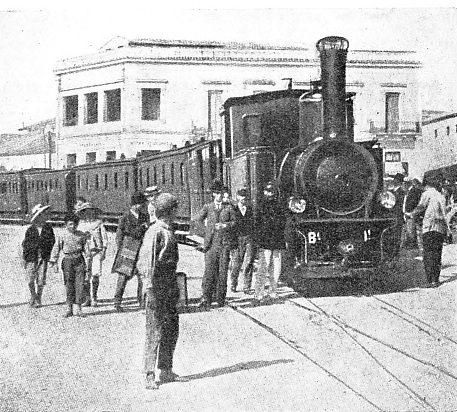

IN THE PELOPONNESUS. Near Aegion Station, on the Piraeus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway. Aegion, 113 miles from Athens, is a busy port on the Gulf of Corinth, exporting oil and currants. The Piraeus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway - known as the PAP - operates 506 miles of metre-gauge track. The Peloponnesus is the southern peninsula of Greece, separated from the mainland by the Corinth Canal.

AFTER centuries of Turkish domination, culminating in the War of Independence, Greece became a sovereign state in 1832. The kingdom was thus born in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. Seven years previously, in 1825, the Stockton and Darlington Railway had begun to operate. But it was not until March 10, 1869, that the first Hellenic railway was opened. This was a line, a little over six miles long, from Athens to the Piraeus, its port.

It is not possible to understand the ramifications of the Greek railway system without learning something of the topography of the country. Further, since every corner of Greece is bound up with legend and history, ancient and modern, in a manner that no other country can emulate, we should be doing the railways scant justice if this aspect were wholly ignored in the present chapter. Occasional references will therefore be found to dates before Christ, and tradition will be blended with statistics.

Athens lies in the centre of the Attic Plain, about four and a half miles from the sea at Phaleron Bay. This bay, which is little more than an open roadstead, was never adequate to the needs of the Athenians. Comparatively early in Greek history, the Piraeus, with its three harbours, was chosen as the port of Athens, although it was two or three miles farther away than Phaleron Bay.

The Piraeus was joined to the capital by the Long Walls, and the two cities formed together a redoubtable fortress. But it was not strong enough to be held at a time of grave national crisis. When the Persians, under Xerxes, invaded Greece in 480 BC, the Athenians, in obedience to an oracle, forsook their city and entrusted themselves to their “wooden walls”, that is, to their ships. Having made this momentous decision they were able, with the help of their allies, to rout the Persian fleet off the island of Salamis, which lies immediately west of the Piraeus.

After the discomfiture of the Persians, the Athenians returned to their city, the acknowledged leaders of the Greeks. Since the leadership of Athens was based on sea power, the shipyards of the Piraeus were of paramount importance. The inter-dependence of Athens and the Piraeus thus dates from the days of Athenian greatness. It is not therefore surprising, when the new means of communication was introduced into Greece, that the two first places to be linked by railway were the capital and its port.

Since 1832 the size of Greece has greatly increased. When the Bavarian prince Otho took possession of his brand-new kingdom, it comprised only that part of the Balkan Peninsula south of a line drawn from the Gulf of Arta in the west to the Gulf of Volo in the east, together with some islands in the Aegean Sea. Greece proper thus included the whole of the Peloponnesus - or the Morea, as it was called in the Middle Ages - and a relatively small proportion of the northern mainland.

In 1864 Great Britain relinquished her protectorate over the Ionian Islands (Corfu, Kephalonia, Levkas, Ithaka, Zante, Paxos, and Kythera) and they became Greek after fifty years of British administration. The accretion of these islands, however, made no difference to the railway mileage. Indeed, to this day, despite the large numbers of islands belonging to Greece, there is not a mile of railway track on any of them.

In 1881 Thessaly and the district of Arta became Greek. The Balkan wars of 1912-13 and the world war of 1914-18 greatly increased the area of Greece, giving her Macedonia, a large slice of Thrace, Crete, most of the Aegean Islands, and much besides. The disastrous campaign of 1921-22 in Asia Minor lost her Smyrna (now Izmir) and its hinterland, Eastern Thrace, Imbros, and Tenedos, which all returned to Turkey. Notwithstanding Greek claims, a group of islands in the south-east Aegean known as the Dodecanese is firmly held by Italy.

This variation of frontiers has naturally been accompanied by a variation in the extent of the relevant means of comm-unication, including the railways. To-day the area of Greece is 50,271 square miles, and the railway mileage is 1,609, no fewer than 660 miles of which are in “new” Greece, that is, in the territory north of the frontier of 1881.

Until May, 1916, the railway system of Greece was cut off from the rest of Europe. Even now certain sections are isolated.

The Athens-Pirasus Railway, which, as we have seen, was the first railway in Greece, was electrified in 1904. It is now operated by the Greek Electric Railway Company. The route is from Concord Square - one of the chief squares in Athens - to the Piraeus via New Phaleron. Of the intermediate stations Monasteraki and Theseion - the latter named after a famous fifth century temple - are in Athens itself. The others are Kallithea, Moschaton, and New Phaleron. New Phaleron has developed into an up-to-date seaside resort on Phaleron Bay. The bay is now used by long-distance sea-planes. Between Concord Square and Theseion stations the line runs partly or wholly underground.

A frequent service is maintained on the Athens-Piraeus Railway all day, trains running normally every fifteen or twenty minutes, but twice as often during rush hours. The gauge is one metre. The journey takes about a quarter of an hour.

Two other railway lines connect Athens with its port. The southern terminus of the standard gauge Greek State Railways and the eastern terminus of the narrow-gauge Pirasus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway are both at the Piraeus. The main object of this triplication of facilities over such a short route is to enable steamer passengers disembarking at the Piraeus with destinations in the interior of Greece to proceed directly to their trains, instead of having to go to Athens and entrain there. Local passengers are not accepted by either of the two trunk lines, as the electric railway is sufficient for their needs.

An extension of the metre-gauge Greek Electric Railway, but on the standard gauge, runs from Concord Square north-west via Herakleion (six miles) to Kephisia, eight and a half miles from Athens. Kephisia, which stands 882 ft above the sea, is popular as a retreat from the heat of the city in summer.

Another line from Athens follows the same route as far as Herakleion, but on metre-gauge metals. It then turns south and finds a way into the low-lying and fertile Attic Peninsula between Mount Pentelicus (3,639 ft), with its renowned white marble quarries, and Mount Hymettus (3,369 ft), tamed for its honey and its sunset glow. The line ends at Lavrion, forty miles from Athens.

Lavrion, a mining town of 6,400 inhabitants, occupies the site of the ancient silver mines that in days gone by were a main source of the wealth of Athens and the financial basis of her maritime empire. After centuries of disuse mining operations were resumed in 1860, when the heaps of scoriae left by the ancient Athenian miners began to be re-smelted.

Six miles south of Lavrion is Cape Colonna, formerly dreaded by mariners. On this promontory, the Cape Sunium of antiquity, are the remains of a famous Doric Temple of Poseidon, built in the fifth century BC. It was at Cape Sunium that the poet Byron exclaimed, “There swan-like let me sing and die!”

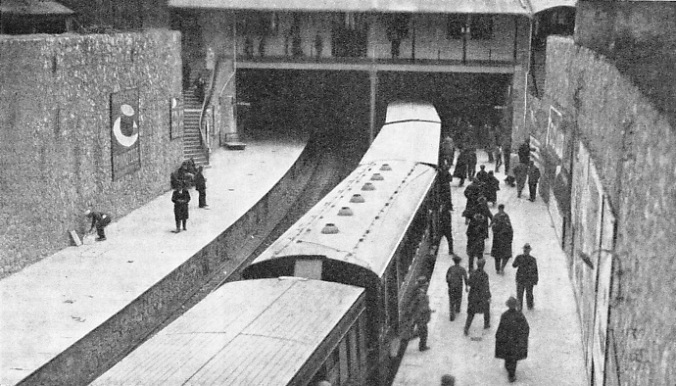

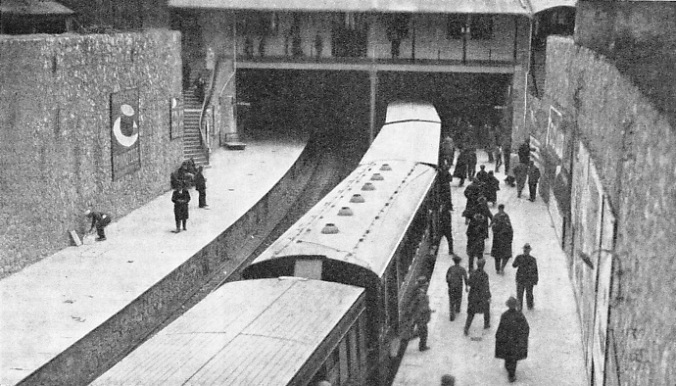

SALONIKA STATION, 315½ miles from Athens, is an important terminus. It serves as an interchange point between the main line from the Pirasus to the Yugoslav frontier and the lines west to Monastir and east through Thrace to Turkey-in-Europe. Salonika is the third largest town in Greece. It is also one of the busiest seaports in the Levant.

The most important of the Greek lines are those of the Greek State Railways. The main line, which is on the standard gauge of 4 ft 8½-in, runs from the Piraeus and Athens through Thebes, Levadia, Larissa, and Platy to Salonika and Ghevgheli, on the Yugoslav frontier, 371 miles from the Piraeus. The distance from the Piraeus to Athens by this line is six and a quarter miles. The first section, to Chalkis, was opened in 1904.

The general direction is from south to north, but the country is so mountainous that a perfectly straight route is out of the question. The few plains, mostly in the river valleys, are separated by high mountain barriers. The railway engineers were often faced with the task of finding a way through apparently impenetrable walls of rock. Barriers that could not be climbed had to be circumvented. That is why the railway route between certain places is much longer than the road.

From Athens to Thebes, for example, the distance by the high road, which runs west and north-west via Eleusis and the Pass of Gyphto-Kastro (“Gypsy Castle”), is only forty-three miles long, while the railway route has a length of fifty-six miles. Eleusis is served by the Piraeus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway, which is described later in this chapter.

The main line of the Greek State Railways at first runs north-east, climbing the pass between Pentelicus, on the right, and Parnes (4,626 ft), on the left. These two mountains form part of the mountain amphitheatre that surrounds the Attic Plain, in which Athens is situated, and separates Attica from Boeotia, of which the chief town is Thebes. Near Dekeleia Station, eight and a half miles from Athens, is the estate of Tatoi, formerly a royal residence and now an orphanage. In the neigh-bourhood is an important aerodrome. Airplanes flying across Europe often land at Tatoi, but seaplanes use Phaleron Bay, as already mentioned.

The railway now makes a wide sweep round the foothills of Parnes and runs west-north-west. Oenoe, thirty-eight miles from Athens, is the junction of a branch line, thirteen and a half miles long, to Chalkis Station, on the western shore of the Euripus, that turbulent strait which separates the extensive island of Euboea from the mainland. Chalkis town, on the opposite side of the strait, is the chief place in Euboea, with a population of 17,300. It is connected with the railway station by a swing bridge across the Euripus.

The next station beyond Oenoe is Tanagra, forty miles from the capital. Tanagra is famous for its terra-cotta figurines, or statuettes, of which large numbers were discovered during excavations in 1874.

Thebes, now a town of 7,113 inhabitants, is fifty-six miles from Athens. It is said to have been founded by Cadmus, a native of Phoenicia or of Egypt and the inventor of the alphabet. Seeking his sister Europa, who had been carried off by Zeus, the greatest of the gods, Cadmus was bidden by the oracle which he had consulted to follow a certain cow. When the cow, after wandering about the countryside, sank down exhausted, he was to found a city on the spot. Cadmus did as he was told. Instead of being grateful to the cow, he decided to sacrifice it to the goddess Athena. Needing some water for the sacrifice, he sent to a neighbouring well, which happened to be guarded by a dragon. The dragon slew his servants, where-upon Cadmus slew the dragon. At Athena’s command he sowed in the ground the dragon's teeth, from which sprang up a number of armed men. These miraculously-born warriors immediately began to fight one another, until only five were left, who became the ancestors of the Thebans.

The god Dionysus, the hero Hercules, and the poet Pindar were all bom or lived in the “seven-gated city”, which must not be confounded with the “hundred-gated” Thebes of Egypt. This northern Thebes was the chief city in Boeotia. For a brief period in the fourth century BC, under the guidance of a general called Epaminondas, it held the leadership of Greece. To the south of Thebes are two famous battlefields - Plataea, where the Persian army was defeated in 479, and Leuctra, where the Spartans were routed in 371 BC.

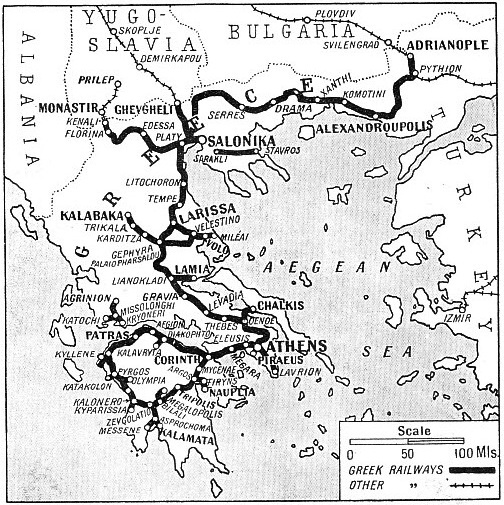

THE RAILWAY SYSTEM of Greece was isolated from that of the rest of Europe until 1916. To-day the Athens section of the “Simplon-Orient Express” runs between the Pirasus, Athens, and Paris through Yugoslavia, Italy, and Switzerland. In addition, through sleeping cars link Athens and Vienna and Athens and Berlin. The Greek State Railways are mainly on the standard gauge; other gauges in use are metre (3 ft 3⅜-in), 75 cm. (2 ft 6-in), and 60 cm (2 ft). The total mileage is 1,609.

The next station after Thebes, Sphinx, sixty-two miles from Athens, is close to Mount Sphingion, the traditional haunt of the Sphinx. This cross-grained creature had a favourite riddle - of no particular interest - which she put to every passer-by, killing all those who could not answer it. No one was able to give the correct solution, and the mortality among travellers was beginning to assume alarming proportions, when Oedipus, King of Thebes, was successful. The Sphinx was so much upset that she committed suicide out of pique.

The line now runs along the dried-up bed of Lake Copais, in which traces of prehistoric drainage systems have been discovered. Levadia, eighty-one miles from Athens, is an industrial town, with a population of 12,585. Chaeronea, four and a half miles farther, is near the site of the battlefield of Chaeronea, where King Philip of Macedon defeated the allied Greeks in 338 BC and destroyed their independence.

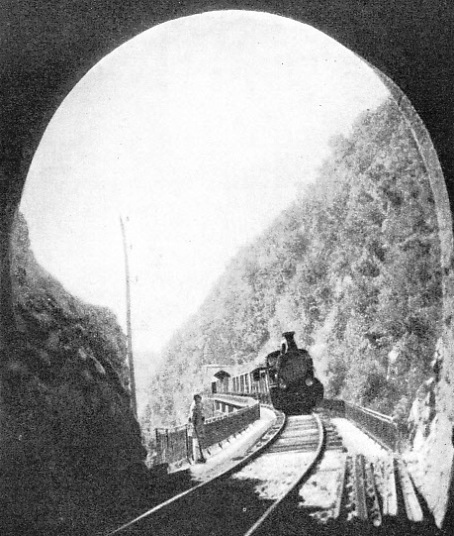

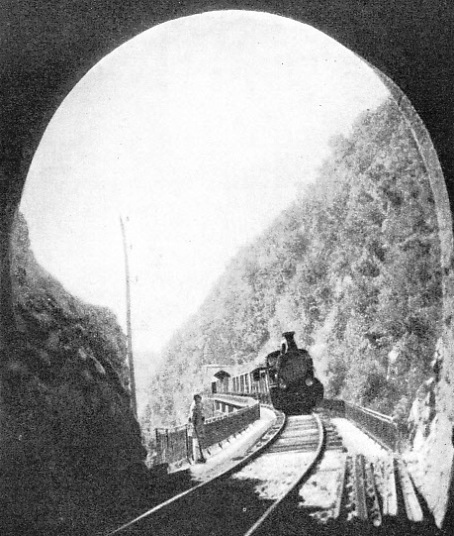

A steep climb has now to be faced. The station of Gravia, 113½ miles, at the summit of the gradient, was originally known as Brallo, and later as Delphi. The last was rather a confusing name, since the station is thirty-eight miles north of the famous sanctuary, which is reached by a road via Amphissa. From the summit-level the line descends for twelve miles, mainly at 1 in 50, through the pass separating Mount Oeta (7,080 ft), on the left, from Mount Kallidromos (4,508 ft), on the right. A tunnel 2,306 yards long is followed by an iron viaduct of 360 yards and seventeen small tunnels during the descent into the valley of the Spercheios.

Lianokladi, or Thermopylae-Hypate, 131 miles from Athens, is a village lying at the foot of the descent. From the station a branch line fourteen miles long runs east to the town of Lamia and the port of Stylis. To the south-east is the Pass of Thermopylae, where the three hundred Spartans under Leonidas sacrificed themselves in 480 BC in a vain attempt to hold up the Persian invasion of Greece.

Historic Country

The line now rises at the same inclination of 1 in 50, which is almost unbroken for nearly twenty-two miles to the summit at Nezeros (Kournovo), 1,919 ft above the sea. Another long descent follows. At Gephyra Palaiopharsalou (“Bridge of Old Pharsalus”), 182 miles from Athens, the main line encounters a line of the narrow-gauge Thessalian Railways which runs from the port of Volo to Kalabaka, a distance of a hundred miles. Kalabaka lies at the foot of the Meteora Cliffs, upon some of which are perched the famous Meteora Monasteries, accessible only by means of ladders. About eight miles to the east of the junction is the battlefield of Pharsalus, where Pompey was defeated by Julius Caesar in 48 BC.

From Larissa, 210 miles, a branch of the Thessalian Railways, with its own station, runs south-east for twenty-five miles to Velestino, on the Volo-Kalabaka line. Another branch of the same narrow-gauge system runs from Volo to Meleae, on the Gulf of Volo. This branch is on the 60 cm (2 ft) gauge; the rest of the Thessalian Railways have a gauge of one metre

(3 ft 3⅜-in).

Larissa, with 23,889 inhabitants, is one of the most important towns in Thessaly. It lies on the right bank of the Peneus, or Salamvria, the chief river of Greece. The Peneus flows to the sea through the beautiful Vale of Tempe, between Olympus (9,794 ft), on the north, and Ossa (6,496 ft), on the south. To the south of Ossa is Pelion (5,300ft). Olympus, with its peak covered in perpetual snow, was the home of the gods. According to the legend, the giants placed Pelion on Ossa when they tried to storm Olympus.

The railway follows the river through the Vale of Tempe. A station in the valley, called Tempe, is 228½ miles from Athens. Papapouli (238 miles), beyond the Vale of Tempe, was formerly on the Turkish frontier and the northern limit of the Greek railway system. Running north to Platy, 293 miles, the main line joins there the line from Salonika to Monastir, to which reference will shortly be made. The direction now is to the east.

THE GREEK ELECTRIC RAILWAY runs for six miles from the Pirseus, the port of Athens, via New Phaleron to Concord Square in Athens. The line was electrified in 1904. An extension, eight and a half miles long, runs from Concord Square to the summer resort of Kephisia.

Salonika, 315½ miles from Athens, is now the largest town in Greece after the capital and its port. It has a population of 236,524. The harbour is of the first importance. The town, partly rebuilt after a disastrous fire in 1917, presents a modern appearance, although its history as Thessalonika goes back to the fourth century BC. The city was visited by St. Paul, who wrote two Epistles to the Thessalonians from Athens. Thessalonika had a troubled history under the Byzantine emperors. In the war of 1914-18 Salonika gave its name to an important theatre of war. After Salonika the main line of the Greek State Railways runs north to Eidomene, 362½ miles, immediately beyond which is the frontier station of Ghevgheli, 364½ miles from Athens, and 371 miles from the Piraeus.

The most important train on this route is the “Simplon-Orient Express”, which runs between Athens and Paris via Nish (where it picks up or detaches a portion from or for Istanbul), Belgrade, Ljubljana (Laibach), Trieste, Venice, Milan, and Lausanne. Through sleeping cars are run between the Piraeus, Athens, and Paris. A restaurant car is provided on part of the journey.

The 364½ miles from Athens to Ghevgheli are covered by the “Simplon-Orient Express” in little over thirteen hours - an excellent time considering the difficulties of the route. The up train takes about the same time. Passengers who wish to travel via Vienna can take the “Arlberg-Orient Express”, which runs between Athens or Bucharest and Paris, and between Bucharest and Calais, by way of Budapest, Vienna, Zurich, and Belfort. The Athens portion, with sleeping car, leaves or joins the “Simplon-Orient Express” at Belgrade.

Another sleeping-car service in connexion with the “Simplon-Orient Express” is between Athens and Berlin, the connecting train from or to Belgrade running via Budapest and Prague.

The track of the main line from Athens to Ghevgheli is laid with rails weighing 89 lb per yard. Forty large 2-10-0 loco-motives, built in Germany in 1925-27, are used for express traffic. Another class of “decapod” is the 0-10-0, of which fifty were built about the same time.

Ordinary Greek trains are of three classes. Even the “Simplon-Orient Express” takes third-class passengers in Greece. As a rule, the rolling stock is admirably kept.

Apart from its historic interest, Salonika is a railway junction of importance. As already explained, the standard gauge line running west to Monastir (Bitolj), in Yugoslavia, coincides for the first twenty-two and a half miles - as far as Platy - with the main line to Athens. Its length is 126 miles, and it serves the towns of Edessa and Florina. The last ten miles of this line, beyond the frontier station of Kremenitsa or Kenali, runs through Yugoslav territory. The Salonika-Monastir railway was of primary importance during the war of 1914-18.

The important standard gauge line, running from Salonika through Macedonia and Western Thrace to Istanbul (Constantinople) belongs to the State Railways as far as Alexandroupolis, 274½ miles from Salonika. It passes through Serres, Drama, and other places well known on the Salonika front during the war. Alexandroupolis, when it belonged to Bulgaria, was known as Dedeagatch. It is a seaport town of 12,119 inhabitants. An express, calling, however, at numerous stations, runs along this route.

Beyond Alexandroupolis the line, which follows the Graeco-Turkish frontier, belongs to the Franco-Hellenic Railway Company as far as the junction of Pythion, on the main line from Sofia and Svilengrad in Bulgaria to Istanbul. This main line is part of the route of the Istanbul section of the “Simplon-Orient Express”.

An isolated 60 cm (2 ft) gauge line belonging to the Greek State Railways crosses the base of the Chalcidice Peninsula from Sarakli, a few miles east of Salonika, to Stavros, forty-one and a half miles distant, on the Gulf of Rendina. A connecting motor bus unites Salonika and Sarakli.

Another isolated system is that of the North Western Railway, which operates on the metre gauge in the south of the province of Acarnania and Aetolia. This starts from the port of Kryoneri, which is united with the important Peloponnesian seaport of Patras by a ferry service across the Gulf of Patras. From Kryoneri the line runs west-north-west for ten and a half miles to Mesolonghi (or Missolonghi), where the poet Byron died in 1824 during the Greek War of Independence. From Mesolonghi the line runs north to Aetolikon, sixteen and a half miles, whence there is a branch to Katochi, six miles south-west.

The main line comes to an end at Agrinion, thirty-eight miles from Kryoneri. Agrinion, a town of 14,500 inhabitants, lies in the centre of a tobacco-growing district. In the neighbourhood are two large lakes - Lake Agrinion and Lake Angelo-Kastro.

The remaining Greek railway of importance - the Piraeus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway - is a metre-gauge system operating mainly, but not wholly, in the Peloponnesus.

The Peloponnesus is a jagged peninsula joined to the mainland of Greece by the slender Isthmus of Corinth. Since 1892, when the four-miles-long Corinth Canal was cut through the isthmus, the peninsula has been technically an island. Most, of its northern coast is separated from central Greece by the Gulf of Corinth, an almost landlocked sea seventy-eight miles long, which opens from the Gulf of Patras, already mentioned.

The Peloponnesus was anciently the home of the Mycenaean Civilization which, flourishing in the second millennium BC about the same time as the cognate Minoan Civilization of Crete, far antedated the age of classical Greece. From Mycenae, its capital in the Argolic Plain, King Agamemnon led a great force across the Aegean Sea to the siege of Troy, which fell - so tradition tells us - in 1184 BC. Eighty years later the Mycenaeans themselves were overwhelmed by conquering Dorians from the north. It was not till six centuries later that classical Greece began to take effective shape.

At the present time the Peloponnesus is divided politically into four maritime provinces surrounding an inland province. The maritime provinces are Achaia and Elis, extending along the north coast; Corinthia and Argolis, reaching from the Gulf of Corinth to the Gulf of Nauplia; Laconia, in the south; and Messenia, likewise in the south, and adjoining Laconia on the west. Laconia contains the ruins of Sparta and of the Byzantine city of Mistra, close by. It was the country of the Spartans or Lacedaemonians, the traditional enemies of Athens and the conquerors of Messenia. The inland province is Arcadia.

Arcadia is a tableland about 4,000 ft above the sea, almost entirely surrounded by mountains. Its climate is strangely bleak and inhospitable. The Arcadians of antiquity were rough shepherds whose mode of life was very different from that imagined by sentimental dreamers bewitched by the poetry of Sidney or by the paintings of Watteau. Shut off by their ring of mountains from contact with the outer world, they lived a life of primitive simplicity, redeemed however by an unexpected passion for music. Strangers were not welcome. Even to-day the railway makes but an apologetic invasion of this mountain-girt plateau.

The Piraus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway - or PAP, as it is locally known - starts from the Piraeus and runs on its own track to Athens, a distance by this route of five miles. Running north from the capital for a few miles, the line then turns west, keeping close to the north shore of the Gulf of Aegina, which contains the historic islands of Salamis and Aegina.

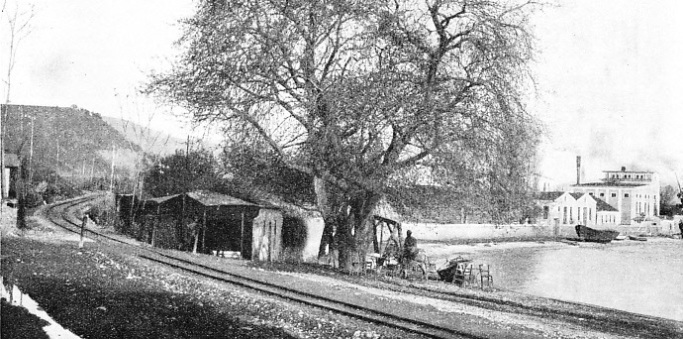

MOUNTAINOUS THESSALY was a formidable barrier to the railway engineers. From Levadia the main line of the Greek State Railways climbs for over twenty miles to the summit-level at Gravia. From here there is a descent, mainly at 1 in 50 and including numerous tunnels, into the valley of the Spercheios, between Mount Oeta (7,080 ft) and Mount Kallidromos (4,508 ft). The photograph shows a train about to enter one of these tunnels.

Twenty-two miles from its terminus the PAP reaches Eleusis, where the Eleusinian Mysteries, in honour of Demeter and Persephone, were held. It is related by Gibbon that the apostate Roman emperor Julian, who reigned from 361 to 363, lost his nerve when he was being initiated into the Mysteries.

Twelve miles farther is Megara, a town of 10,441 inhabitants, occupying the site of the small city-state which founded Byzantium - later Constantinople and now Istanbul. Beyond Megara the line finds a precarious way along the cliffs by the route known as the Kake Skala, or “Evil Staircase”. Here the robber Sciron used to lurk. Sciron, after relieving his victims of all that they possessed, made them wash his feet. While they were thus occupied he kicked them over the cliffs into the sea, where they were devoured by a pet turtle. Sciron was slain by the hero Theseus, who disposed also of the robbers Procrustes and Sinis. The “bed of Procrustes” is too well known to need explanation. Sinis, who haunted the Isthmus of Corinth, had an engaging habit of bending down two adjacent saplings and tying the arms of the traveller he had robbed to one of the trees and the legs to the other. He then let go, and observed his victim’s disintegration in mid-air.

Beyond the station of Kalamaki, fifty-six miles from the Piraeus, the railway approaches the Isthmus of Corinth and the Corinth Canal, which it crosses by a road and railway bridge a hundred yards long and 144 ft above the water level. The next station, Loutraki, two and a half miles farther, is nearly three miles south of the popular watering-place of that name.

A short run from the bridge brings us to the station of Corinth, sixty-one and a half miles from the start. The station is in New Corinth, a modern town of 9,940 inhabitants, about four miles north-east of ancient Corinth. “It is not everybody,” says the Latin poet Horace, “who can get to Corinth.” But the passenger by the PAP Railway is one of the lucky few. The ancient Corinthians were prosperous traders who lived, at the zenith of their fame, in a state of luxury so vivid and so notorious that it surprised even their contemporaries. Their reputation was such as to induce the Apostle Paul to exclaim in one of his Epistles to the Corinthians, “Evil communications corrupt good manners.”

From Corinth to Patras

From the railway point of view Corinth is the most important junction in the Peloponnesus. The westward continuation of the PAP keeps close to the northern coast-line all the way to Patras. A branch to the south runs to Argos and across a corner of southern Arcadia to another junction called Zevgolatio (the name means “Junction”), in Messenia. Here the line is joined by the southward continuation of the line from Patras, after which it runs south to Kalamata. We will first deal with the westerly continuation from Corinth.

Leaving the station the railway skirts the coast of the Gulf of Corinth, passing the citadel of Acrocorinth, the ancient city’s precipitous acropolis, which rises to a height of 1,886 ft. To the south towers the peak of Kyllene (7,780 ft). Kiaton, eighty and a half miles from the Piraeus, is the station for the ruins of Sicyon, once an important city-state famous for schools of painting and sculpture, and for its general Aratus, refounder of the Achaean League.

The next station of importance is Xylokastron, seventy-seven and a half miles from the terminus, after which the line, still keeping near the coast, crosses the base of an outlier of the Arcadian mountain Chelmos (7,727 ft). The River Krathis, fed by the Arcadian Styx - there really exists in Greece a river called the Styx - is soon crossed, and the train pulls up at Diakophto, 110 miles.

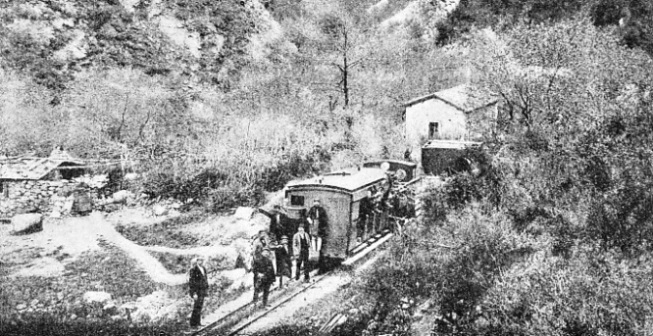

From Diakophto a rack railway, with the gauge of 75 cm (2 ft 6-in), climbs inland for thirteen and a half miles up the gorge of the Bouraikos to Kalavryta, just inside the Arcadian border. The journey takes two hours up and one and three-quarter hours down. A little over half way is the station of Megaspeleon, for the famous monastery of that name, founded in the Middle Ages. It was accidentally burnt down in July, 1934. The track is nothing but a series of precipitous ledges, iron viaducts, and short tunnels, while the river foams in the gorge far below.

Beyond Diakophto numerous turbulent streams are crossed. Aegion, 118 miles, is a considerable port of 11,011 inhab-itants, exporting oil and currants. It may not be generally known that the word currant is derived from Corinth. Along the whole coast from Corinth to Patras are innumerable currant-grape vineyards, yielding perhaps the most important product of the area.

A STATION NAMED AFTER A TEMPLE. Theseion, a suburban station on the Greek Electric Railway from the Piraeus to Athens, was named after a famous Greek temple of the fifth century BC. Between Theseion and Concord Square, in the heart of Athens, the line is partly underground. A frequent service of trains is maintained all day.

Nearing Patras the line crosses a small stream called the Selemnos. Those who bathed in the stream were anciently said to forget their love. “If there is any truth in this story,” observes the geographer Pausanias, “great riches are less precious to mankind than the waters of the Selemnos.” Patras, 143 miles from the Piraeus, is the largest town in the Peloponnesus and the third port of Greece, after the Piraeus and Salonika. It has a population of 61,278, and exports currants and wine. It is a busy port of call for steamers from the Adriatic to the Piraeus via the Corinth Canal, and is used in addition by many other passenger and cargo vessels.. Although the PAP Railway continues unbrokenly beyond the town, Patras is considered to be the end of the section from the Piraeus and Athens.

An express train, provided with a restaurant car, and calling at nearly all stations to Corinth and at the principal stations thereafter, runs from Athens to Patras in seven hours. Another train, stopping everywhere, takes eight and a half hours.

The journey time will, it is expected, shortly be reduced to five and a half hours by Diesel rail-cars. In 1935 eight express rail-cars and eight others for local services were ordered, as well as three steam locomotives.

Beyond Patras the PAP keeps to the coast until it reaches the Plain of Elis, when it turns inland for a time. From Kavasila, forty and a half miles from Patras, a branch runs west for three and a half miles to Vartholomio, where it forks, one line going northwest to Kyllene, six miles farther on, and the other continuing west to Loutra, six and a half miles from the junction.

Pyrgos, sixty-one and a half miles, is the junction for a seven-miles branch to Katakolon, a currant-exporting seaport. Pyrgos is also the station for Olympia, although the point of divergence from the main line is at Alpheios, four and a half miles farther on. The Olympia branch is eight and a half miles long.

Olympia, lying in a pleasant valley watered by the River Alpheios, is the spot where the Olympic Games were held. These games were celebrated without interruption every fourth year from 776 BC to AD 393 - that is, over a thousand years. They are said to have been instituted by Hercules in honour of the Olympian Zeus, whose gold-and-ivory statue, by Pheidias, was one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The games were valued so highly by the ancient Greeks that the calendar was reckoned by Olympiads - periods of four years between the festivals.

A sacred truce was proclaimed throughout Greece during their celebration. The truce had the effect of temporarily stopping the warfare that was in antiquity the normal condition of civilized life. To such an extent was this so that the city-states, instead of declaring war on one another, were in the habit of making peace for a certain number of years.

The modern Olympic Games were inaugurated at Athens in 1896, and they have been held every four years since, except in 1916, when the war stopped them. The word Olympiad now means the festival itself, and not the interval between two of them.

There is no road-rail competition in this part of Greece. The roads are few and far between, and they are impassable in wet weather. The train service on the Olympia branch is reasonably generous, although the trains stop at every station and take fifty minutes from Pyrgos to Olympia, and five minutes less in the reverse direction.

Beyond Pyrgos the PAP runs slightly inland, roughly parallel to the coast. The next station of note is Kalonero, ninety-six miles, junction for a short branch (four miles) to Kyparissia, a small town of 4,443 inhabitants. The ancient Kyparissia was the port of Messene.

From Kalonero the line strikes inland to Zevgolatio, 114 miles, where it meets the direct cross-country line from Corinth, shortly to be described. The course of the railway is now almost due south, through the fertile province of Messenia.

It was the fertility of Messenia that caused the ancient Lacedaemonians, who inhabited the neighbouring country of Laconia, to set about its conquest. The conquest was so complete that the Messenians left in their country were turned into slaves, or helots, as they were called.

Asprochoma, 131 miles, is the most southerly junction in Greece. The main line comes to an end at the port of Kalamata, officially Kalamae, 134 miles from Patras. A branch three miles long runs west from Asprochoma to Messene. Seven trains operate daily in either direction between Kalamata and Messene by way of the junction.

Kalamata, with a population of 28,955, is the chief town in the province of Messenia. It exports oil, wine, currants, figs, oranges, melons, and other produce of this exuberant region. Messene was one of the cities built by the victorious Theban general Epaminondas after the battle of Leuctra, which caused the downfall of Sparta in 371 BC. The walls of the ancient city are among the finest surviving examples of ancient military fortification. There are no expresses on the section from Patras to Kalamata and Messene. The morning train from Patras, stopping at nearly all stations, takes nine and a half hours to cover the 134 miles to Kalamata.

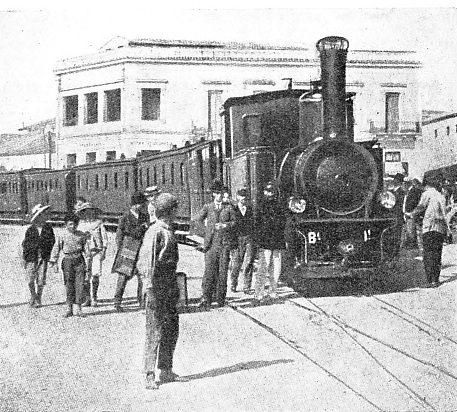

PATRAS, the largest town and chief seaport in the Peloponnesus, exports currants and wine. The station is 81½ miles from Corinth and 138 miles from Athens. The main line of the Piraeus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway keeps close to the coast all the way from Corinth. A continuation of the railway runs south-west and south to Pyrgos, Zevgolatio - where it is joined by a cross-country line from Corinth - and Kalamata, in Messenia.

Equally sedate are the trains on the cross-country line from Corinth to Kalamata via Zevgolatio. At first this line goes south, passing Acrocorinth on the right It soon has to climb the Pass of Dervenaki, past Nemea, where Hercules killed the Nemean lion in the performance of one of his Twelve Labours.

Descending from the pass, the train enters the Argolic Plain, home of the Mycenaean Civilization. Mycenae itself has a railway station, twenty-seven and a half miles from Corinth. It was in the acropolis of this ancient city that the German archaeologist Schliemann made his momentous discovery in 1873-76. He unearthed from the shaft-graves in the citadel the treasure that established the existence of a civilization which hitherto had been relegated to the realm of legend.

Six miles farther is Argos, celebrated for its sanctuary of the goddess Hera, wife of Zeus. Argos, now a local headquarters, with a population of 10,504, is overlooked by its formidable acropolis, the Larisa, which is 985 ft high. A branch line runs south-east, via Tiryns, to Nauplia, seven miles away. Tiryns was an important contemporary of Mycenae, standing on a natural ridge in the Argolic Plain. Its cyclopean walls, with their casemates and galleries, ascribed to an age between the 16th and 13th centuries BC, are still partly standing. Nauplia is a beautifully situated modern seaport town of 7,113 inhabitants, dominated by the Hill of Palamedes (708 ft). In 1827 it became the temporary capital of Greece. It exports grapes, currants, tobacco, and cotton.

Railway Across Arcadia

From Argos the line continues to run south, past Myloi Navpliou (“Mills of Nauplia”), the site of Lerna, where Hercules performed another of his Twelve Labours in destroying the Hydra. This creature had nine heads. As soon as a head was cut off, two others took its place. The middle head was immortal. With the help of his faithful servant, lolaus, Hercules over-came the Hydra by burning away the eight mortal heads and burying the ninth under a huge rock.

Beyond Achladokampos, fifty-three miles from Corinth, the line crosses a ravine by a viaduct 275 yards long and 230 feet high, in the course of its tortuous climb into Arcadia The main direction is now west-south-west.

Tripolis, seventy-six miles, capital of the province of Arcadia, is a modern town of 14,397 inhabitants situated at an important road junction. One road, served by postal cars, of which there are many all over Greece, supplementing the railway service, goes south to Sparta, another road centre.

From Bilali, 101½ miles, a branch line three miles long runs north to Megalopolis, the ancient Arcadian capital founded by Epaminondas about the same time as Messene.

At Zevgolatio, 127 miles from Corinth, the line joins the railway from Patras, described earlier in this chapter. The route via Tripolis to Zevgolatid and stations beyond is sixty-eight miles shorter than that via Patras. It is the only railway that dares to cross Arcadia, though the rack-and-pinion line running south from Diakophto enters the inland province before reaching Kalavryta.

The rest of the Peloponnesus south of this cross-country line is devoid of railways. A proposal for a railway from Tripolis to Sparta has never yet come to fruition. Since, however, in the south of the Peloponnesus the roads are reasonably good and the service of postal cars is being developed, the inhabitants of Laconia are not cut off from the world. In the circum-stances, it is unlikely that the mileage of the PAP Railway will be increased to any appreciable extent. Nor is there much probability of railway development in Central and Northern Greece. Proposals for an extension of the North Western system from Agrinion into Albania have not materialized, and the extreme northwest of Greece is still without railways.

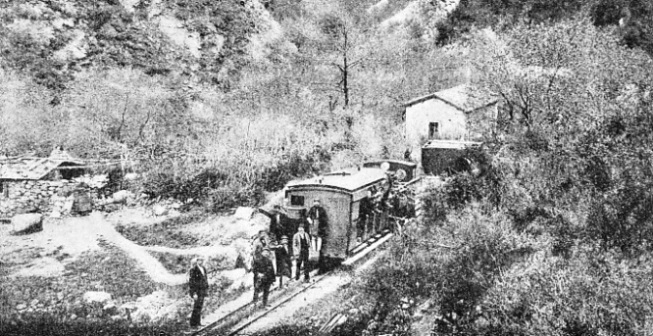

RACK-AND-PINION PROPULSION is used on the 2 ft 6-in gauge railway from Diakophto, on the Pirseus-Athens-Peloponnesus Railway, to Kalavryta, in Arcadia. The line, which is thirteen and a half miles long, climbs inland from the Gulf of Corinth up the gorge of the Bouraikos.

You can read more on “Electrification in Europe”, “In Central Europe” and “The Orient Express” on this website.