RAILWAYS OF BRITAIN - 52

“There be three things which make a nation prosperous, a fertile soil, busy workshops, and easy conveyance for men and commodities from one place to another.” So wrote Francis Bacon four centuries ago. The fertile soil this county had; the busy workshops had been given us by those who had put to use the mighty power of steam; and the easy conveyance came with the highest embodiment of that power, the locomotive, the thing that moves of itself, the most wonderful achievement of human ingenuity, for it is nearest to life.

RICHARD TREVITHICK

Heat may or may not be a mode of motion; but it is assuredly a cause of motion, and the commonest cause. Far back in the development of mankind came the discovery and subjugation of fire; then came the water boiling in the pot; and ages afterwards the bold adventurer who put the lid on the kettle and was the first to imprison steam, as he who invented the spout was the first to put steam under control. Who they were no one knows, nor in most cases even in our own time does any one know the name of the real inventor. The man who invents is not the man to talk and persuade, but to do. He is dumb, and many of the inventions made by the man are ascribed to the master who found the money to patent them with and the agents to introduce them. And such is not the only sort of false representation in this connection, for the grim giant steam, as dumb as the inventor, did the work that was wanted and gave the nation the prosperity usually ascribed to the adoption of a theory of economics, and is doing it still wherever the theory is rejected.

Railways have never been given the credit that is their due. The majority who knew them in their infancy had little but evil to say of them. That majority’s children gave as cold a welcome to the bicycle, and we know how their children’s children treat the motor-car. The railways had a harder fight than these to get a footing in the world, but they were here when we were born and seem as natural as the wind and tide.

They were an invention, and there is no one more generally disliked than the inventor until after his death, when he gains nothing by his work, and then the community claim him as one of themselves and boast of what “we” have done. He is the great disturber of capital, the encourager of the speculative, the introducer of new ways, the founder amid many failures of industries competing with industries that seem to have existed for ever, of trades taking the place of trades that are always at their best in the final stage of the contest that ends in their replacement. It is easy to sneer at antiquity until we are reminded that we are doing as our ancestors did under similar circumstances; and the opponents of railways are secure of at least a little sympathy as one result of that knowledge of the past required to realise what railways have done for us.

We are approaching a period of power when with electricity and internal combustion there promises to be no limit to speed; but steam raised the rate of movement to fivefold what it was a century ago. “What is the use of all this hurry?” some will think it right to say, just as in those far-off days when man first made fire “What is the use of it?” was asked in the manner of the time. The answer is - “Look around you! Where is the man that walks, except for exercise, when he can ride? Who rides in a slow train when he can travel in a fast one? Where is the man who will spend ten hours in a vehicle when he can find another that will take him the same distance in three?”

Speed? There is fascination about it that all feel, whether they admit it or not, for there is nothing in the animal world that would not go faster if it could. Who without a thrill has seen the Cornishman sweep by on the way to the west - whizzing through the woodland, whirring down the slope, thundering over the bridge, booming through the cutting, humming along the level, burring on the bank; woods and slopes, tunnels and bridges, cuttings and banks, each with a note of its own?

The locomotive is the most interesting of machines for the same reason as the steam-hammer is the most popular of machine tools; there is no mistaking its purpose or the means by which it does its work. And the story of our home railways, of which it is the central figure, is of more importance than that of any other industry. Let us consider it again with the aid of new light from old and new sources that time has disclosed and trade caution no longer keeps back, though if ever there were a subject on which one has to go warily it is railway history, for never was a path so strewn with misapprehensions and misprints.

We all know what we mean by a railway, but it is as well to remember that the railway is essentially the road, the rail-way, on which the rolling stock is moved by men, horses, steam-engines, or whatever other engines may share it with them or replace them. The railway began with the road, and it will end with the road.

The history of the road specially prepared for fast or heavy traffic would take us back a long way; let it be enough to note that on the 4th of August 1555 there was a tram from the west end of the Bridge Gate in Barnard Castle for the repairing of which Ambrose Middleton, in his will, left twenty shillings. The word tram seems to have been used in the north of England and south of Scotland as descriptive of the special track and the truck that ran on it. The track was of timbers laid lengthways; the trucks were hauled by men or horses. It was these railways with their rails of timber “exactly straight and parallel”, running along the old wayleaves, that Roger North found in 1676, on which the “carts with four rowlets” carried the coals from the collieries to the Tyne.

When these rails were first faced with iron we do not know, but in 1734 cast-iron wheels with an inner flange were in use near Bath; in 1767 Reynolds placed plates of iron on the old railway at Coalbrookdale with the flange inside; and in 1776 John Curr laid at the Nunnery Colliery near Sheffield a cast-iron plateway in which the iron was a right angle in section, the vertical of which was outside and kept the wheels on the horizontal track - an idea that caused a riot, the inventor having to remain in hiding for three days and nights in a neighbouring wood until the fury of the populace had abated.

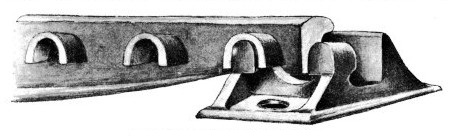

Thirteen years afterwards John Smeaton’s pupil, William Jessop, improved upon this, at Smeaton’s suggestion, by placing a narrow iron edge rail on his line between Nanpantan and the Loughborough Canal and using inner-flanged wheels, thus removing the flange from the rail to the wheel and introducing into the world a railway about which there can be no dispute. The rails were in yard lengths, about 40 lb. to the yard, double-flanged in section, with a curved lower flange that spread out to form a foot, through which they were spiked down to cross sleepers. What they were like any one can see by going to South Kensington, where, among the railway antiquities, “Cast Iron Edge Rails, M. 2472”, came from the original track which was of 4 ft. 8½ in. gauge. They are rough and rusty, but there is thought in the old iron; do not pass them by with indifference.

JESSOP RAIL (1789)

Rails were cast without the feet in 1797 in the Newcastle coalfield: they were placed on the so-called “chairs”, and as the lines were braced with cross sleepers - apparently the “trams” or beams from which the name comes - the main features of the permanent way had been reached before the close of the eighteenth century. But nearly all the old tram-roads had flat rails, and among the most important of these in railway story were the Pollok and Govan, working in 1778, now part of the Caledonian; and that at Merthyr Tydvil - to the Glamorgan Canal, opened in 1794 - which is now part of the Taff Vale.

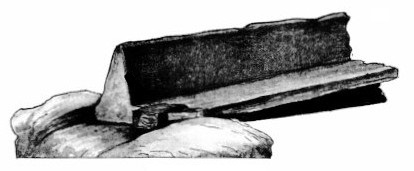

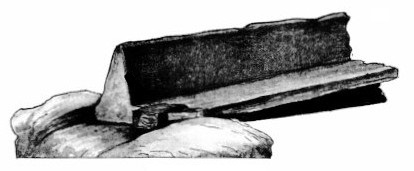

One other should be mentioned as a survival, the old lime line from Ticknall to the Ashby Canal constructed in 1799 by Benjamin Outram, who laid so many lines that the word tram was said to have come from the last syllable of his name. But there were trams before there were Outrams, and the derivation is now only quoted as an aid to memory. This Ticknall tram-road with rails like Curr’s was bought by the Midland in 1846. It has never been used, but in order to maintain their rights the company still run on it, once in the October of every year, a wagon loaded with coal solemnly drawn by a horse.

OUTRAM’S TICKNALL TRAM-RAIL (1799)

In 1799 it was proposed to lay a line from London to Portsmouth, and for the first portion of this the Surrey Iron Railway Company was formed, and obtained its Act of Parliament in 1801. This was the first railway company, the first public railway, and the first Railway Act so-called, though it was not the first Act in which a rail-way was authorised. The rails were 4 in. wide and 1 in. thick, with an arched flange ½ in. thick and 3½ in. high resting direct on stone-block sleepers. The gauge was 4 ft. 7 in. outside the flange; inside, as our present gauge is measured, it was about 4 ft. 6 in.; the four-wheeled wagons were 5 ft. wide, 2 ft. deep, and 8 ft. long, and they were worked by horses. The revenue was derived from tolls - there is one of the toll sheets at South Kensington - coals, for instance, being charged for at the rate of threepence per chaldron per mile. The first section of the line, opened on the 1st of June 1804, ran from Wandsworth to Croydon across Mitcham Common; the extension, for which an Act was obtained in 1803, ran from Croydon to Merstham. This portion was taken over by the Brighton Company as their first purchase, and some of it forms part of their present system.

Between the Surrey’s Act of 1801 and the Stockton & Darlington’s in 1821, there were no fewer than nineteen Railway Acts, five of which were allowed to lapse. Among the others there were, in 1802, the Carmarthenshire and the Sirhowy, now absorbed by the North Western; in 1804 the Oystermouth (Swansea to the Mumbles), which is still working independently, and is in that sense the oldest existing railway; in 1808 the Kilmarnock & Troon, now part of the Glasgow & South Western; in 1809 the Gloucester & Cheltenham, and the Forest of Dean, now included in the Midland and the Great Western; and in 1817 the Mansfield & Pinxton, now part of the Midland.

Like their predecessors for fifty years or more, they were plate ways rather than railways, and the men who laid them were the platelayers, whose name has ever since been applied to the layers and repairers of the track. In several cases these old flat roads were the nuclei of later schemes, and, like the old Surrey, they can be traced in the sections which were abandoned. They were there long before the coming of the steam-engine, and it was upon one of them that a locomotive made its first journey.

At Redruth in 1797 lived two men to whom the world owes much. William Murdock was in the house in Cross Street in which he invented gas lighting, and, within a stone’s throw, at Moreton House, lived Richard Trevithick. Murdock had been in Cornwall for eighteen years as engineer to Boulton & Watt, and was to leave it in 1799 to be the superintendent of their works at Soho. The two were opponents in business, Murdock being very much engaged in erecting Watt’s engines and looking after Watt’s interests, while “Captain Dick” was the most prominent of the Cornishmen who were using every endeavour to evade or improve upon Watt’s patents.

In 1759 John Robison, before he sailed for Quebec, was helping Watt to invent a locomotive, and Watt included the use of steam for land transport in his patents. But he seems to have left the matter alone, and certainly discouraged any experiments about it among the staff of the Birmingham works. Murdock, however, away at Redruth, had a freer hand, and took up this problem of making a wheeled carriage that would move of itself.

One evening, wishing to put his model to the test, he went to the walk leading to Redruth church. This was narrow, kept rolled like a garden walk, and bounded on each side by a high hedge. It was dark and he was alone. Lighting the lamp under the boiler he got up steam, and off started the locomotive with the inventor in chase of it. Soon he heard shouts of terror. Following up the machine he found that the cries proceeded from the parson who, going into the town on business, was met on the lonely road by the fiery little traveller. According to the parson’s daughter, her father and mother, returning from the town, were somewhat startled by a fizzing sound, and saw a little thing on the road moving in a zigzag way. Murdock was with it; her parents knew him well. They understood that he wished the experiment to be kept secret, and she did not recollect ever hearing of it afterwards. Whichever story be accepted, it is clear that Murdock made a model, and that it moved of itself on Redruth church path.

He seems to have made two models at the least. One, according to Wilson, reporting to the firm on the 9th of August 1786, had a 1½ in. stroke; another, which is in the Birmingham Art Gallery, had a stroke of 2⅛ in.; and about this, or a third one, there is a letter of importance among those now at Soho which cleared up the mystery why Murdock did not persevere with his work on the self-moving engine.

Boulton, going into Cornwall, met a coach near Exeter in which he caught sight of Murdock. He got down at once, and Murdock also alighted. According to Boulton they had a parley for some time. “He said he was going to London to get men; but I soon found he was going there with his steam carriage to show it and take out a patent, he having been told by Mr. Wm. Wilkinson what Sadler has said, and he has likewise read in the newspaper Symington’s puff, which has rekindled all William’s fire and impatience to make steam carriages. However, I prevailed upon him to return to Cornwall by the next day’s diligence, and he accordingly arrived here this day,” 2nd of September 1786, “at noon, since which he hath unpacked his carriage and made it travel a mile or two in Rivers’s great room, making it carry the fire-shovel, poker and tongs. I think it fortunate that I met him, as I am persuaded I can cure him of the disorder or turn the evil to good. At least I shall prevent a mischief that would have been the consequence of his journey to London.” In short, Boulton & Watt had enough to do in their own line, and it did not suit them to lose Murdock or to launch out on to another that might be risky. And so William Murdock, the most loyal of men, was deprived by the policy of the firm of the honour of introducing the locomotive.

Murdock had ventured on high-pressure, and with high-pressure steam the Soho firm would have nothing to do. But Richard Trevithick was a high-pressure man in several senses, and from his youth up had made it his peculiar study. Naturally inventive, he was led on to invent a locomotive. From the newspapers he may have heard of what Symington and others were busy at, or he may have been told, perhaps by Murdock himself, of what had occurred on the church path; at any rate eleven years after that he had a model ready.

In 1797, when he was six-and-twenty, he had married and made his home at Moreton House; and here a few weeks afterwards the model was tried. His friend Davies Giddy, in time Davies Gilbert, President of the Royal Society, had brought with him Lord and Lady De Dunstanville - De Dunstanville, before his peerage Francis Basset, being the great landowner of the district - and Giddy was stoker, and Lady De Dunstanville was engine-man and turned on the steam to the first high-pressure steam-engine.

Shortly afterwards another model was made which ran round the table, or the room. Its boiler and engine were in one piece; hot water was poured into the boiler, and a red-hot cast-iron block put into the oval flue, just like the hot iron in old-fashioned tea-urns. It had a vertical double-acting cylinder, 1·55 in. in diameter, and a 3·6 in. stroke, sunk in the boiler, and the piston rod ended in a guided crosshead, the connecting rods reaching down to crank pins in the two driving wheels which measured 4 in.; and there was a fly-wheel driven by a spur-wheel on the crank shaft. That model is now at South Kensington (M. 1835), where it can be compared with a copy of Murdock’s model (M. 2413) which it in no way resembles.

The model was experimented with and improved upon in many ways for some three years before Trevithick ventured on building a machine of full size. While this was in hand he entered on an inquiry as to whether the wheels of a self-propelled carriage ought to be smooth or toothed, and he came to the conclusion that with smooth wheels it would have sufficient hold on any reasonable gradient. To test this he hired the post-chaise that had been kept for Watt’s use when he was at Redruth sixteen years before; and with Giddy he took this out on to a road near Camborne, and there, unharnessing the horse, these two men proceeded to work it uphill by applying their strength to the spokes of the wheels. Several times on several slopes they moved it forward in this way, and in no case was there any slip. The result confirmed his expectation that the wheels might have smooth tyres, but, to guard his rights, in the patent of 1802 he expresses himself - “We do occasionally, or in certain cases, make the external periphery of the wheels uneven, by projecting heads of nails or bolts, or cross-grooves, or fittings to railroads when required; and in cases of hard pull we cause a lever, bolt, or claw, to project through the rim of one or both of the said wheels, so as to take hold of the ground; but in general the ordinary structure or figure of the external surface of these wheels will be found to answer the intended purpose.”

On Christmas Eve 1801 the engine was ready, and the first load of passengers was moved by steam on what is known in the neighbourhood as “Captain Dick’s Puffer”. The rain was coming down heavily, the road in places was rough with loose stones, and the gradient such that the wise cyclist walks his machine up, but “she went off like a little bird” for three-quarters of a mile up Beacon Hill at what is now Camborne railway station and home again. Over their Christmas dinner Trevithick and his cousin Andrew Vivian became partners, and they were soon in London armed with letters of introduction from Giddy to Humphry Davy, who introduced them to Rumford, both of whom helped them in securing their patent.

On the 22nd of August 1802 Trevithick was at Coalbrookdale erecting a pumping engine, and wrote from there to Giddy, “The Dale Company have begun a carriage at their own cost for the railroads, and are forcing it with all expedition”, but of this little further is known. Later in the year he was in Cornwall building another locomotive which he brought with him to London in 1803, where he learnt from the varieties of paving that such machines would be more efficient on a smooth iron road. And in October he was at the Penydaren Ironworks, near Merthyr Tydvil, building the engine with which the railway era is frequently said to begin.

This was designed for many uses and worked on the tram-road for the first time on Monday the 13th of February 1804. “It worked very well and ran up hill and down hill with great ease, and was very manageable. We had plenty of steam and power,” wrote Trevithick to his friend Giddy; and on the following Monday he wrote, “The engine, with water included, is about five tons. It runs up the tramroad of two inches in a yard” - twice as steep as Bromsgrove Lickey - “forty strokes per minute with the empty wagons. The engine moves forward nine feet at every stroke. The steam that is discharged from the engine is turned up the chimney about 3 feet above the fire, and when the engine works forty strokes per minute, 4½ feet stroke, 8¼ inches diameter of cylinder, not the smallest particle of steam appears out of the top of the chimney, though it is but 8 feet above where the steam is delivered into it, neither at a distance from it is steam or water found. The fire burns much better when the steam goes up the chimney than when the engine is idle. I intend to make a smaller engine for the road, as this has much more power than is wanted here. This engine is to work a hammer. We shall continue our journey on the road to-day with the engine until we meet Mr. Homfray and the London engineer, and intend to take the horses out of the coach and draw them home. The coach axles are the same length as the engine axles so the coach will run very easily on the tramroad.”

The London engineer had been sent down by the Government with a view to ordering similar engines if this one passed certain tests, these being - “The wagon engine is to lift the water in the pipes, then go by itself from the pump and work a hammer, then wind coal, and lastly to go the journey on the road with a load of iron!”

On the Tuesday the great run took place from the works to the Navigation House. “Yesterday,” wrote Trevithick to Giddy, “we proceeded on our journey with the engine; we carried 10 tons of iron, five wagons, and seventy men riding on them the whole of the journey. It is above nine miles, which we performed in four hours and five minutes. The engine, while working, went nearly five miles per hour; no water was put into the boiler from the time we started until we arrived at our journey’s end. The coal consumed was 2 cwt. On our return home, about four miles from the shipping place of the iron, one of the small bolts that fastened the axle to the boiler broke, and all the water ran out of the boiler, which prevented the return of the engine until this evening.”

The engine continued working, and ten days afterwards was tried with 25 tons of iron. “We were more than a match for that weight,” writes Trevithick to Giddy; and continues, “the steam is delivered into the chimney above the damper; when the damper is shut the steam makes its appearance at the top of the chimney; but when open none can be seen. It makes the draught much stronger by going up the chimney; no flame appears.” On the 10th of July we have Homfray writing to Giddy, “Trevithick went down the tramroad twice since you left us, with 10 tons each time,” so that it must have been kept on duty for some months before it was withdrawn to work the rolling mill. William Richards was its first driver, and he drove no other engine all his life though he was engine-driving at Penydaren until he was over eighty. So far from Trevithick’s engine being broken up, it was kept in repair as long as the ironworks lasted, and then little was left of what it was originally built of. Very different all this from the usual story! But the first engine that ran on an iron road is of too much importance for legends about it to be repeated when the truth is known.

During the rest of the year Trevithick was busy about the country superintending the erection of his high-pressure stationary engines. In September he was at Newcastle arranging with Christopher Blackett, the owner of The Globe newspaper, to supply him with a locomotive for Wylam Colliery. This was erected at John Whinfield’s works at Gateshead, and was completed in May 1805. The working drawings are at South Kensington (M. 1310). Like the Penydaren engine, on which she was an improvement, she had no bellows draught, Trevithick having abandoned it as soon as he found the steam-blast sufficient. The statement, and the argument built on it, that in 1815 he proposed to use vanners, must be due to some one who never read the specification (No. 3922), which is not for a locomotive but for quite a new kind of stationary engine in which the steam acted as a cushion on the water and was used over again instead of being allowed to escape.

This Gateshead engine was the first with flanged wheels, but these did not suit the Wylam track which then had wooden rails. Three years afterwards these were replaced with the cast-iron rails on which, in 1813, Puffing Billy had an easier task. And so she was taken off and used for many years as a stationary engine. On a temporary iron railway in Whinfield’s yard she had worked satisfactorily, being the first engine to work on an iron edge rail. Every one in the district interested in engineering went to see her; and with her the history of the locomotive begins in the north.

D uring the next ten years several other engines were built by Trevithick, who was a man of many inventions. For some years he was busy with a steam dredger for the Thames and his iron tanks for water cisterns. He was the engineer of the first Thames Tunnel, that of 1809; two years afterwards he built the first steam threshing machine, for Hawkins, and followed this by the steam plough. In 1812 came the Cornish pumping engine as we know it; and in 1815 his screw propeller for steamships for which he proposed a boiler with small tubes through which went the water, not the fire; being, in fact, the first water-tube boiler, foreshadowed in his locomotive boiler.

uring the next ten years several other engines were built by Trevithick, who was a man of many inventions. For some years he was busy with a steam dredger for the Thames and his iron tanks for water cisterns. He was the engineer of the first Thames Tunnel, that of 1809; two years afterwards he built the first steam threshing machine, for Hawkins, and followed this by the steam plough. In 1812 came the Cornish pumping engine as we know it; and in 1815 his screw propeller for steamships for which he proposed a boiler with small tubes through which went the water, not the fire; being, in fact, the first water-tube boiler, foreshadowed in his locomotive boiler.

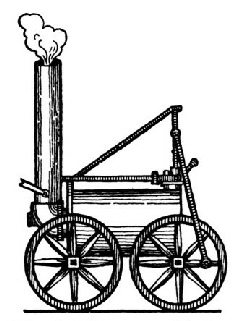

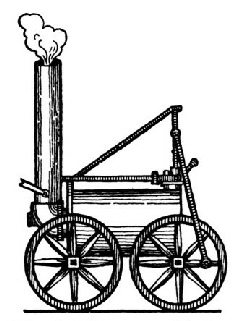

THE FIRST PASSENGER ENGINE (1808). (From Trevithick’s visiting card.)

In 1808 he was in London running his Catch-me-who-can at twelve miles and more an hour on his circular iron road where Torrington Square now is, hauling on the track an open carriage - as he had done Homfray’s - in which were passengers at a shilling a head, being in fact the first passenger engine. The track was on longitudinal sleepers, and the engine weighed over eight tons and was more like a modern locomotive than the Gateshead one, for he had abandoned the cog-wheels and also the fly-wheel which still survives on our traction engines and steam rollers.

During 1814 he became connected with a scheme for working certain mines in Peru in the Cornish manner, and he built at Hayle nine of his pumping engines which were shipped for Lima, three of his friends going out with them. Their reports were so favourable that in October 1816 he left for the land of promise, and for seven years he prospered so that he became worth nearly half a million of money; and then the War of Independence broke out by which he was ruined, the natives, looking upon him as a Spanish emissary, blowing up his engine-houses and throwing the machinery down the shafts. With difficulty he escaped with his life, and had to make his way northwards through the forests alone into Costa Rica, where he conceived a scheme for a railway across the isthmus.

In 1805 and thereabouts he had been frequently on Tyneside among the enginemen and others. Twenty-two years afterwards, when upset at the mouth of the Magdalena, he was lassoed from drowning - and an alligator - by Bruce Hall, who took him to Robert Stephenson at Cartagena. “Is that Bobby?” asked Trevithick. “I have nursed him many a time!” And so he had. He and Robert Stephenson left South America together, one full of his project for running a railway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the other to help on the Liverpool & Manchester.

When George Stephenson made Trevithick’s acquaintance he had just moved to the West Moor Pit at Killingworth as brakesman. His struggle upward from herding cows at twopence a day had been long and was not over. It is easy to give the years, reeling them off one after the other, and forget that each consisted of twelve months; and it was more than two hundred and fifty months before he began to earn £2 a week. He is credited with more than his due, for in the days when the opposition to railways was at its fiercest it was necessary for parliamentary and advertising purposes to magnify his reputation as an authority on every branch of engineering. He was not the “father of the railway engine” - that honour is Richard Trevithick’s - nor was he “the inventor of railways”. But his knowledge of the whole matter, derived from the machines and the men who made them, was immense; and his organising powers remarkable. He was in the front all through the fight against the old order of things, the one conspicuous figure to whom the railwaymen looked for leadership; around him the storm centred; and it is to him more than any man that we owe our railway system.

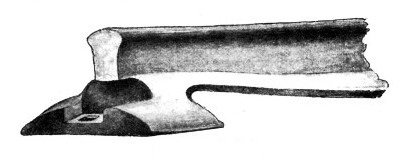

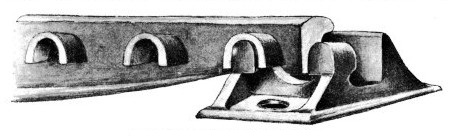

In 1811 John Blenkinsop patented (No. 3431) a rail with “a toothed rack or longitudinal piece of cast iron or other fit material having the teeth or protuberances or other parts of the nature of teeth standing either upwards, downwards or sideways” with the intervals of which “a wheel having teeth or protuberances” would engage; and thus he became the originator of our mountain-climbing railways. He was the agent of the Middleton Colliery, and to carry the coals down into Leeds, three and a half miles away, he hit upon this contrivance and laid out the road on which the levels were few and the gradients many. As shown by the Museum specimens (M. 2325) he did not use a rack but “protuberances”, as he called them, these being a series of almost semicircular ears arranged along the side of the rail half an inch from the upper edge like so many small arches, each about 3 in. across, ⅜ in. thick, and projecting some 2¼ in. There were seven of these ears to each rail, which was 41 in. long. The top of the rail was smooth and the carrying wheels of the engine were smooth. The driving wheel between them worked outside the rail, not on it, its projections being rounded so as to run easily between the rounded ears.

BLENKINSOP WHEEL

Blenkinsop patented the principle of the rack and wheel, not the engine or “carriage” as he called it. The engines he used were designed and built by Matthew Murray, and had two cylinders, as recommended by Trevithick in his patent of 1802, so arranged that the cranks were at right angles to each other, thus getting over the difficulty of starting. They were the first engines with two cylinders, the first with six wheels - 2-2-2 in fact - and the railway was the first that was financially successful. The first engine made its first run from the colliery to the wharf at Leeds on the 24th of June 1812, its load at the finish being eight wagons carrying twenty-five tons of coal and fifty people. In regular work the trains were composed of as many as thirty wagons, and considering the gradients and the weight of the engine, which was only five tons, Blenkinsop was probably correct in thinking he could not do without his protuberances.

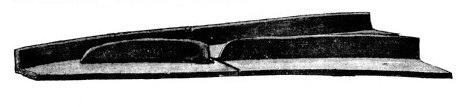

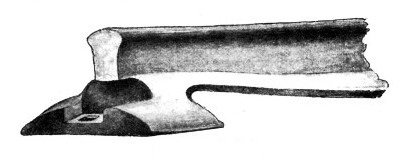

In 1812 Stephenson was appointed engine-wright at Killingworth High Pit at a salary of £100 a year, and in riding about inspecting the collieries belonging to the same owners and others he became interested in the new railway between the Kenton and Coxlodge collieries and the Tyne. This had the Blenkinsop rail and engines. Next year, at Mr. Blackett’s suggestion, William Hedley, who had found by an experiment confirming Trevithick’s experience that smooth wheels had sufficient adhesion on smooth rails for the gradients on the Wylam track, built Puffing Billy.

BLENKINSOP RAIL AND CHAIR (1811)

At first this, like his experimental engine of 1811, which was a failure, had four wheels, but as it broke down the cast-iron plate track, it was in 1815 made an eight-wheeler, each group of four wheels being carried on a sort of bogie. In 1830 the line was relaid with cast-iron edge rails, and then Billy was altered and became a four-wheeler again. This engine from the first was a great improvement on the horses, and was actually kept at work until 1862; it is now at South Kensington. The sister engine, Wylam Dilly, which worked on until 1867, is in the Edinburgh Museum.

Stephenson carefully watched them working on the road that ran past the cottage in which he was born in 1781, and came to the conclusion he could improve upon them as well as on the Coxlodge engines; and in 1814 he built Blucher, his first locomotive. To begin with, this was rather a failure, but as soon as he turned the waste steam into the funnel as Trevithick had done he doubled the power and made it a success, thus leading on to his Killingworth engine of 1815. At first this had coupling-rods placed upon inside cranks between the wheels, but owing to one of the crank axles getting bent he replaced the rods with the chain gearing familiar to us in the bicycle.

WYLAM RAIL (1808)

The same chain-coupling with the sprocket wheels was used in his engine of 1816. In 1817 the Duke of Portland ordered one of these engines for his Kilmarnock & Troon line, the first locomotive to be worked in Scotland, but the cast-iron wheels damaged the cast-iron track and were ingeniously replaced by wooden ones.

Some of the Scottish tram-roads are very early in date. When Johnnie Cope fought the battle of Prestonpans he placed his artillery on the tram-road from Tranent to Cockenzie; the Carron Ironworks put down lines soon after their opening in 1760; most of the collieries in Midlothian, Fife, Lanark, and Ayrshire had their iron roads; and in 1810 matters were so far advanced that Telford surveyed the route of a railway from Glasgow to Berwick. In the south steam traction did not progress very much, but it did not die out. All along a few Trevithick engines appear to have been working in South Wales; and in 1814 William Stewart built a locomotive for the Park End Colliery in Gloucestershire, which was tried on the Lydney line, now the joint property of the Midland and Great Western.

The engines were waiting for the roads to be strong enough to carry them. Cast-iron rails continued to be used owing to their cheapness, but rails had here and there been made of wrought iron for some years. When Timothy Hackworth went to Walbottle Colliery as foreman of the smiths he found rails of malleable iron which had been laid by Nixon in 1805; and in 1808 wrought-iron rails were in use on the Tindale Fell line, a specimen of which, merely a square bar spiked to stone blocks, is at South Kensington (M. 2487). Then in 1820 came John Birkinshaw (No. 4503) to do with his mill for the rail what Henry Maudslay did with his slide-rest for the engine cylinder. To quote Thomas Baker, the poet of the “Steam Engine”: -

“By rolling-mill he these tough rails produced,

And these, without improvement, still are used,

No hammer-work, unseemly weld, or flaw

Was in the work of famous Birkinshaw!”

But enough of these old roads. The year the first engine went to Scotland a railway was projected from Darlington to Stockton-on-Tees. By it was the experience gained on the colliery lines to be utilised for the public benefit; with it the railway age, as most people know it, really opened. How it rapidly developed under Stephenson’s influence from a railroad to be worked by horses into one worked by steam, and led to all being worked by steam, we shall see in the story of the North Eastern.

You can read more on the “London’s First Railways” and “Story of the Locomotiove” and “When Railways Were New” on this website.

uring the next ten years several other engines were built by Trevithick, who was a man of many inventions. For some years he was busy with a steam dredger for the Thames and his iron tanks for water cisterns. He was the engineer of the first Thames Tunnel, that of 1809; two years afterwards he built the first steam threshing machine, for Hawkins, and followed this by the steam plough. In 1812 came the Cornish pumping engine as we know it; and in 1815 his screw propeller for steamships for which he proposed a boiler with small tubes through which went the water, not the fire; being, in fact, the first water-

uring the next ten years several other engines were built by Trevithick, who was a man of many inventions. For some years he was busy with a steam dredger for the Thames and his iron tanks for water cisterns. He was the engineer of the first Thames Tunnel, that of 1809; two years afterwards he built the first steam threshing machine, for Hawkins, and followed this by the steam plough. In 1812 came the Cornish pumping engine as we know it; and in 1815 his screw propeller for steamships for which he proposed a boiler with small tubes through which went the water, not the fire; being, in fact, the first water-