© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

The Snow Plough and its Work

How the railways fight against the track-

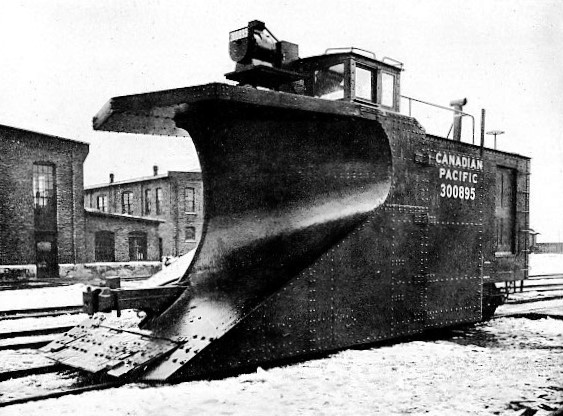

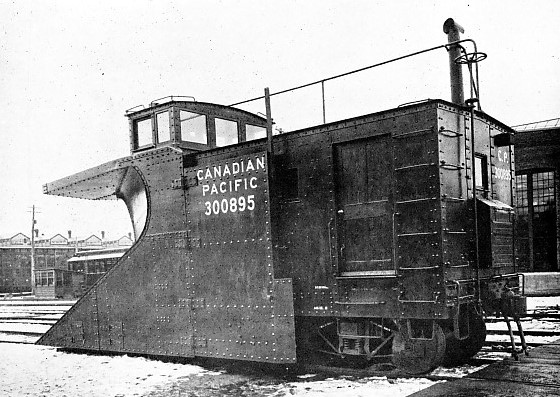

FRONT END OF WEDGE SNOW-

IN countries which are liable to heavy snowfalls the railways are tied up under such visitations far more effectively than are those in temperate climes by the fog fiend. This enemy of the railway operator, despite the most valiant and herculean efforts, will oftentimes refuse to release its grip for days on end, bringing traffic to a standstill. The snow-

The scudding white fleece is no mean foe. It will fill a deep cutting to the contour of the country, and upon a level stretch will pile up huge hills which are not easily shifted. To force a passage by hand labour through such obstructions is a hopeless task; and in order to expedite the removal of the snow, so as to reduce the traffic interruption to the minimum, the engineer has devised wonderful mechanical appliances. Although they displace vast armies of men armed with shovels, the latter cannot be dispensed with entirely. In fact, often gangs have to be rushed up to extricate the plough after it has become stalled in a difficult position, and perhaps can neither advance nor retreat.

The oldest and most common form of mechanical snow-

The method of operation is very simple. The pointed nose of the plough is driven into the drift or bank, when, merely by pushing it forward, the snow displaced by the prow is deflected along each side of the scoop, and thrown clear of the track. Sometimes the snow, which may have banked well after drifting, does not yield readily to the powerful sustained pressure of the locomotives behind. Then more drastic methods are adopted. The machine backs down the cleared track a short distance, and then drives headlong into the drift, this bucking being continued until either the bank is overcome or the plough is defeated. One great advantage of this form of snow-

The wedge-

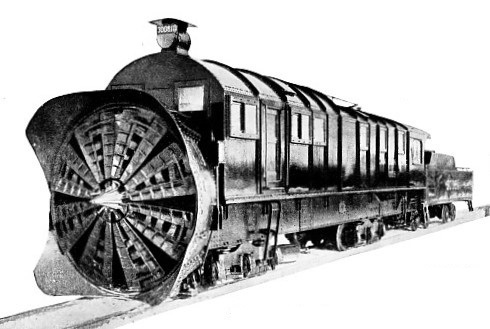

The rotary snow plough s the railway engineer’s finest weapon for combating the forces of winter, notwithstanding that at times the resistance is stern, the struggle for supremacy is bitterly contested, and progress is slow. Although in its present perfected form this tool is of comparatively recent date, the idea itself is by no means new, the first patent having been taken out 45 years ago. Perhaps it is not a strange circumstance, but the invention is of Canadian origin, and it was evolved, not by a railway engineer, but by a dentist! This was J. W. Elliott, a resident of Toronto, and he christened his conception a “compound revolving snow shovel”. Fundamentally, it resembled the machines of to-

The invention appears to have been premature: at all events, it was not adopted, a result probably due to the lack of demand for such an equipment in those days.

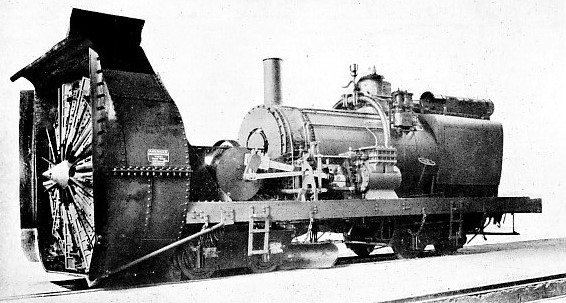

FRONT END VIEW OF THE LATEST C.P.R. ROTARY SNOW-

Later, however, another inventor, Orange Jull, revived it. The main feature in this instance was a knife-

This experiment served to suggest certain improvements, such as the ability to throw the snow to one side or the other as required. Another machine was built upon the improved lines by the Cook Locomotive Company, now amalgamated with the American Locomotive Company, and was put into operation upon the Union Pacific in the winter of 1887. By the aid of this first practical rotary blockades which had defied the railway’s ordinary snow-

Through the enterprise of the American Locomotive Company, assisted by suggestions for improvements which have been extended by the men who have had to use the machines, and who thus are in the best position to discover weak points, the rotary has been brought to a high pitch of perfection. In its present form the scoop wheel, which is the vital feature, comprises ten hollow, cone-

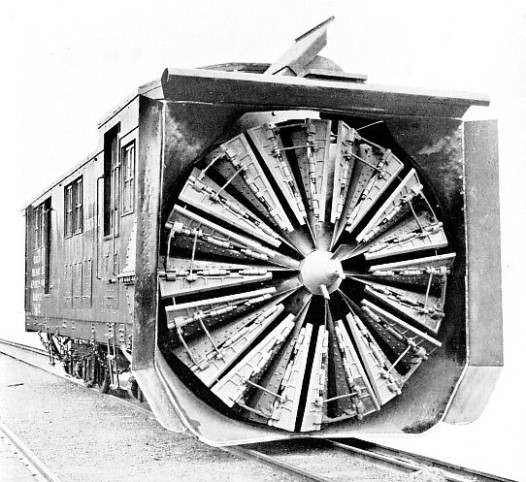

FRONT VIEW OF THE CHICAGO, MILWAUKEE AND PUGET SOUND RAILWAY'S HUGE ROTARY

SNOW-

The operation of the machine is very simple. The machine, its boiler and driving mechanism, are mounted upon a heavy truck, which is completely enclosed in a cab for the accommodation of the crew. By means of windows in the front end above the drum the pilot has a clear view of the snow ahead. All the controls are within immediate reach, including the steam whistle, by means of which, according to a pre-

The plough is pushed into the snow bank, the wheel being set in motion — about 150 revolutions a minute — before it touches the snow. The knife edges cut the snow, which, dislodged, is forced down the scoop until it reaches the periphery of the wheel. Further travel is prevented by the drum, and the snow can only escape when the end of the scoop comes opposite the shoot in the hood. The centrifugal force set up is sufficient to enable the snow to be thrown in a continuous fountain high into the air, and some 60 or more feet from the track.

Now and again obstructions will be encountered, and unless the fates are kind trouble follows. Sometimes the machine is derailed; but more often than not it is the knives which suffer. There is a heavy sudden jolt, and if the obstruction be a boulder or a good-

is taken at the moment. Repairs can be effected later at leisure. With the big drifts and banks where ice and snow have packed hard, forming a substance almost as dense as rock, bucking is practised. The plough with the engines backs down the track, and then the obstruction is. charged. The pressure is maintained until the obstruction obtains the upper hand, causing the wheel to slow down, when the signal to back out is given hurriedly before there is an opportunity for the machine to become stalled. Bucking is continued until the machine drives its way through the packed mass, or is compelled to acknowledge defeat. In the latter event there is no alternative but to turn to manual labour—to blast and shovel out the obstruction as if it were rock. On the steep mountain grades the battle between the railway-

SIDE VIEW OF THE HUGE ROTARY SNOW-

To-

Although all the railways of North America which traverse the great mountain ranges are compelled to maintain a battery of rotaries, and are engaged in grim struggles during the winter, probably the Canadian Pacific, owing to its more northern situation, and the heavy varied character of its mountain section, experiences the toughest task to keep its line open. In fact, the struggle became so fierce that those responsible for the maintenance of communication called for larger and more powerful machines in order to enable them to do their work more efficiently. “Give us a plough that will not break down, and strong and powerful enough to drive through any snowbank, and we will keep the lines open”.

GENERAL VIEW OF THE CANADIAN PACIFIC WEDGE SNOW-

The request did not go unheeded; its significance was appreciated. The railway company’s engineers set to work, and they produced a snow-

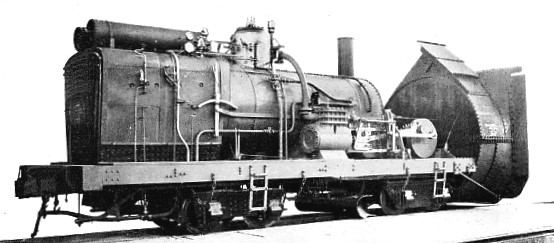

THE ROTARY SNOW PLOUGH UNHOUSED, showing boiler and engine for driving the scoop wheel.

Attached to the plough is a tender of the locomotive type. It has been made especially long, measuring 32 feet over the frames, and carries 16 tons of coal and 7,000 gallons of water, so that the total length over frames of this machine is over 80 feet.

Two of these powerful ploughs were built as a first instalment and were dispatched to the mountains immediately upon completion in January, 1911. Although the winter was not so severe as those experienced in previous years, and consequently an opportunity did not arise to submit the machine to a most exacting test to ascertain its capabilities, yet the work which was carried out therewith served to indicate this railway had secured a plough such as they desired. With the aid of only one locomotive instead of two, drifts of packed snow and ice 250 yards in length were forced with ease, speed being maintained from one end of the cut to the other. Ability to tackle the avalanche with its concealed trees was demonstrated also, because trunks 4 inches in diameter were cut up by the knives as if they were straws.

FRONT VIEW OF UNHOUSED ROTARY SNOW PLOUGH, showing scoop wheel and its driving gear.

You can read more on “The Canadian Pacific Railway -

“Snow Sheds -