© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

The Magic of the Andes

Climbing Through the Clouds in South America

THE INTERNATIONAL TRAIN leaving Antofagasta. The Antofagasta (Chile) and Bolivia railway system links the Chilian port of Antofagasta with Western Bolivia, the Argentine, and with Peru.

NO railway journey in the world could present more astonishing contrasts than that which takes the traveller across the South American continent from Buenos Aires to Valparaiso. For hundreds of miles over the rolling pampas of Argentina not a single hill is to be seen -

Gradually, however, the line is rising, although at Mackenna, 236 miles out of the Argentine capital, the level attained is only 774 ft above the sea. The great plain, green and brown in colour, stretches away to the horizon. Clusters of trees round the estancias, or farms, and herds of cattle, driven by swarthy gauchos, are the only relief to the monotony of the scenery. Cattle-

The rise of the line begins slowly to grow more perceptible, but as yet giving no hint as to what lies ahead. On reaching Villa Mercedes, 428 miles from the capital, the train has risen to 1,683 ft above the sea. In the province of San Luis, immediately beyond, hills begin to appear. But not until we are approaching Mendoza do we notice that far off to the west there is rising, as it seems, sheer out of the plain the vast mountain barrier that runs the whole length of the South American continent, the great chain of the Andes.

Well may so immense an obstacle as this have held up the railway builders who desired to link up the railway systems of Argentina and Chile. For many years there had existed a rough trail, following the bends of the Mendoza River through winding valleys and rocky gorges, fording turbulent glacier-

But better communication became imperative. The fertile country round Mendoza -

As far back as 1854 railway communication had been proposed by a man named Wheelwright, who had been responsible for building the first railway in South America, between the towns of Caldera and Copiapo, in Chile. But he was regarded as a visionary, and no interest was taken in his idea. In 1869 the brothers Clark, who had conducted a survey for an inter-

Owing to financial difficulties -

Owing to financial difficulties -

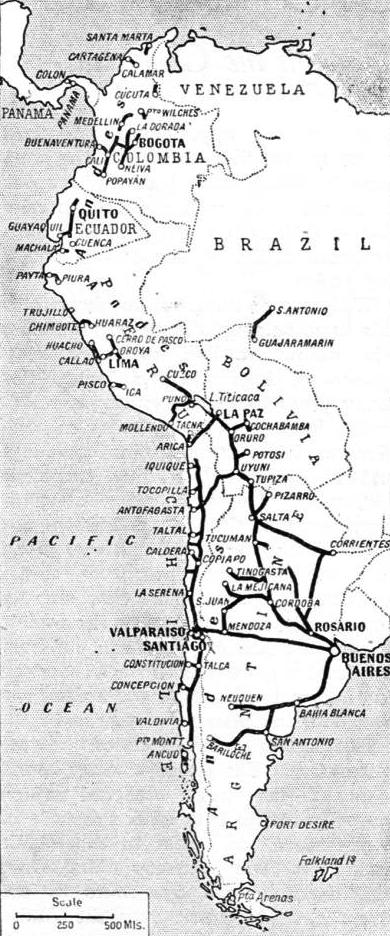

THE RAILWAYS OF SOUTH AMERICA, which have conquered the barrier of the Andes, are shown on this map.

At last, in 1896, a new company was formed in London, called the Transandine Construction Company, and a concession was obtained from the Chilian Government to purchase the section of line already built, and to carry the remainder through to completion. The railhead advanced rapidly; the section from Los Andes up to Juncal was opened for traffic in 1906, the next stretch up to Portillo in 1908. A tunnel was bored through the crest of the Cumbre ridge, 2,600 ft below the pass, but 10,450 ft above sea level and just under two miles long. Then the Chilian and Argentine sections were linked, and the Transandine Railway, a triumph of railway engineering, was opened throughout its length.

Quick Climbing

It is not so much the height attained on the journey that makes the Transandine Railway remarkable; ten thousand feet up is remarkable enough, but, further to the north, in Peru and Bolivia, railways pursue their lengthy courses at well above that figure, and at least five railway summits exceed the 15,000 ft mark. The outstanding feature of the engineering of the Transandine line is the extreme rapidity with which the summit level is attained.

At Mendoza it is necessary to change trains. The Buenos Aires and Pacific Railway has brought us across Argentina in the spacious rolling-

A powerful tank locomotive is at the head of the train. It is equipped for rack-

Leaving Mendoza, the train makes directly for the foothills of the Andes, and passes for twelve miles through the fertile Mendoza valley. This fertility seems strange at first, because the country on this side of the Andes is practically rainless. But the melted waters of glaciers come pouring down the Mendoza river, and careful irrigation on an extensive scale is responsible for this verdure.

A Glacier Bursts

This garden at the foot of the Andes is itself 2,470 ft above sea-

Directly the railway finds the gorge in the mountain wall by which it is to penetrate deep into the heart of the range, the verdure is left behind. Little except bare rock will be seen for many miles, save where it is overlaid, at the higher altitudes, with snow and ice, and the occasional appearance of scrub and stunted trees on the lower mountain slopes. Yet the scenery is one of constantly increasing magnificence, in which distance and the dignity of the great peaks play their part equally.

At Cacheuta, twenty-

Volcano and Earthquake

Miles of the railway were wiped out. Massive steel bridges were wrenched from their bed-

The journey arouses all the sensations associated with the conquering of an untamed world. Upwards and onwards the train travels, crossing and re-

Thirty-

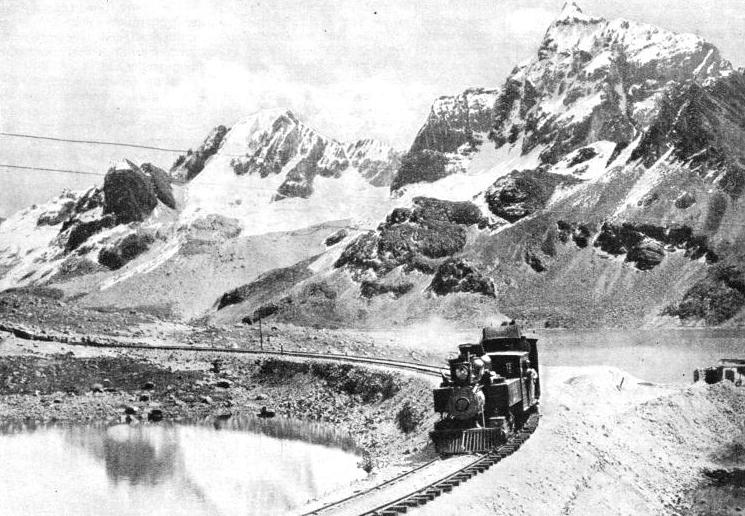

AMONG THE SNOW-

Still the railway climbs steadily. The maximum gradient on the adhesion section is limited to 1 in 40, but that is quite steep enough for our panting locomotive. The line twists and turns, arduously, cautiously. Suddenly there appears ahead a rock-

At length the greatest giants of the Andes come into view. It is from Las Vacas, up a lateral valley, that we catch sight of Tupungato, rearing its snowy head to a height of 21,550 ft; and just beyond Puente del Inca there comes into view the greatest of all the mountains in the Western Hemisphere, Aconcagua, whose proud summit, 23,080 ft above the level of the sea, falls short of Everest by only a little over six thousand feet.

At Puente del Inca Nature also has some engineering work of note to display. This is the bridge, or puente, from which the railway station takes its name. A natural and not an artificial wonder, this arch of stone clears the gorge of the Cuevas with a span of 70 ft and a width of 90 ft, 65 ft in height above the water. The level of the railway, at exactly one hundred miles from Mendoza, has now risen to 8,915 ft above the sea.

Steeper climbing lies ahead, and the steel track now appears intermittently between the ordinary running rails, for the making of the steeper ascents. Leaving Puente del Inca, the train mounts the Paramillo de los Horcones, the Paramillo itself being the moraine of an immense glacier that existed in prehistoric times. Swinging across the Horcones river by a fine steel bridge, the track enters the narrow gorge of the Cuevas, where rack-

The mountains now close in ahead of the line, higher than ever. Steeply up from Las Cuevas rises the old post track, now a motor road, finding the lowest possible level for crossing the crest of the ridge at the Cumbre Pass, 12,796 ft above the sea. Here is found the boundary between Argentina and Chile, with the great bronze figure of Christ and below it the inscription: “Sooner shall these mountains crumble into dust than the people of Argentina and Chile break the peace which they have sworn to maintain at the feet of Christ the Redeemer”.

But the railway traveller sees nothing of this unique boundary post, except a distant peep, right on the skyline, from the western end of the tunnel. For his train is thousands of feet below, in the heart of the rock, being carried through from one watershed to the other by the Cumbre Tunnel, which is but 90 yards short of two miles long. The crossing of the frontier is, however, made audible by the clanging of the bell which the train passes in the middle of the tunnel.

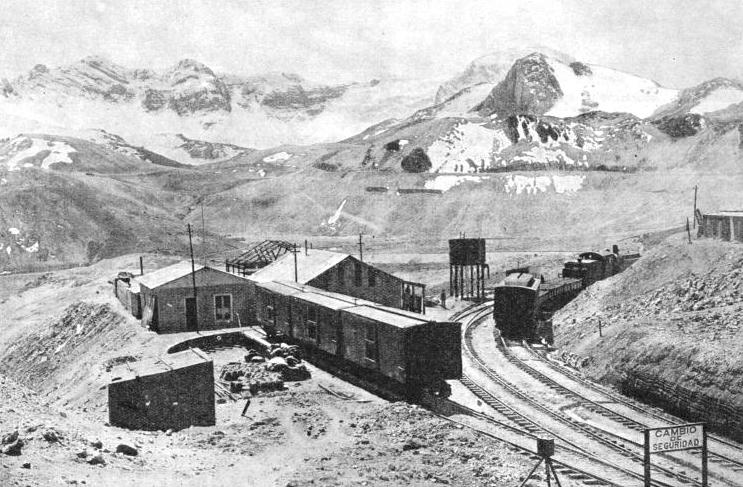

THE HIGHEST STATION IN THE WORLD on a standard gauge railway is at Ticlio, 15,610 ft above sea-

It was Koebel, in his book, “Modern Argentina”, who was so impressed with the wonder of this journey that he wrote, on reaching the summit level, “All this while -

We emerge from the tunnel on the Chilian side at Caracoles. Ahead of us the valley drops profoundly, and we see wide sweeps of the line far below, over which presently we shall be travelling. The greatest difficulties were experienced in the engineering of the next section of the line westwards, owing to the fact that the Pacific slope of the Andes is so much steeper than the eastern slope. In no more than forty-

Mysterious Waters

The railway line curves and twists on itself, by means of some remarkable spiral location work. Rack-

DEVASTATED. Snow-

To speed up the working over these steep inclinations between Caracoles and Los Andes, steam has now given place to electricity. A powerful articulated electric locomotive of the 1-

Just before Portillo the train skirts the Inca Lake, set among the mountains at a level of over 9,000 ft -

The Metre Gauge

From Los Andes the journey is swiftly made down to Valparaiso, no more than eighty-

B y changing at Llai-

y changing at Llai-

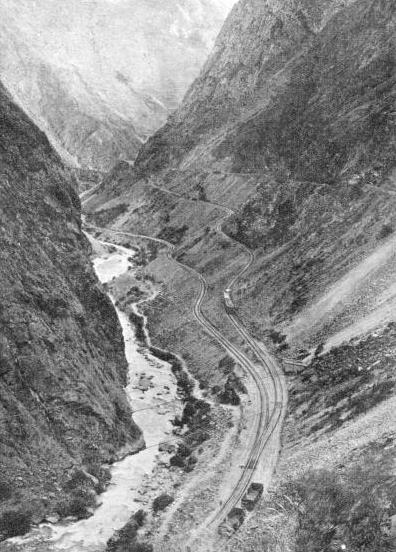

ZIGZAGGING TO GAIN HEIGHT, the Central Railway of Peru winds its way through the Rimac Gorge on the Callao-

As we travel northwards through Chile, the character of the country changes. In the south there is much forest land; in the centre, assisted by irrigation, the land is largely arable; in the north it becomes a desert region. But it is in the arid north that the wealth of Chile largely lies. For it is here that there are the great nitrate deposits, and high up in the Andes other minerals, copper and silver in particular, exist in immense quantities. It is in search of these minerals that railways have been laid on “the roof of the world”. Travelling north by the longitudinal trunk of the Chilian State Railways, we intersect, at Baquedano, the first of a series of railways which start at sea level on the Pacific coast, two in Chile and two more in Peru, climb, in a couple of hundred miles or less, to heights of 13,000 ft and more, and drop down into lofty valleys in the heart of the great chain of the Andes. In two instances a lake is reached on which there plies a railway steamer service, over a route 120 miles in length, the whole of which is 12,500 feet above the sea.

The railway thus intersected at Baquedano is the Antofagasta (Chile) and Bolivia Railway. It is in a veritable desert that the two lines meet. This is the centre of the great nitrate country, where no rain falls. and not a blade of grass is to be seen for many miles; all the water has to be brought from long distances, and the only signs of life are at the colonies which surround the nitrate factories.

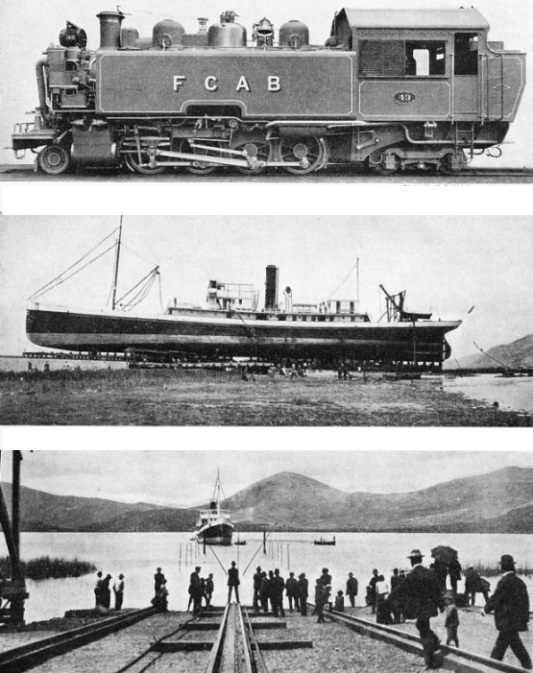

FOR MOUNTAIN SERVICE. This British-

LAUNCHING A SHIP ON TOP OF THE ANDES. The railway company operates a steamer service across Lake Titicaca. The photograph shows the launch of the Inca. This ship was built in Hull, sailed to South America, and was then transported in parts to be reassembled on the lake.

AFTER THE LAUNCH. The Inca on Lake Titicaca, 12,500 ft above sea-

It was in 1873 that the first stretch of line was begun from Antofagasta inland, to bring nitrate down to the coast for ship-

When the track of the Antofagasta Railway first began to find its way up into the mountains, it was on the extremely narrow gauge of 2 ft 6-

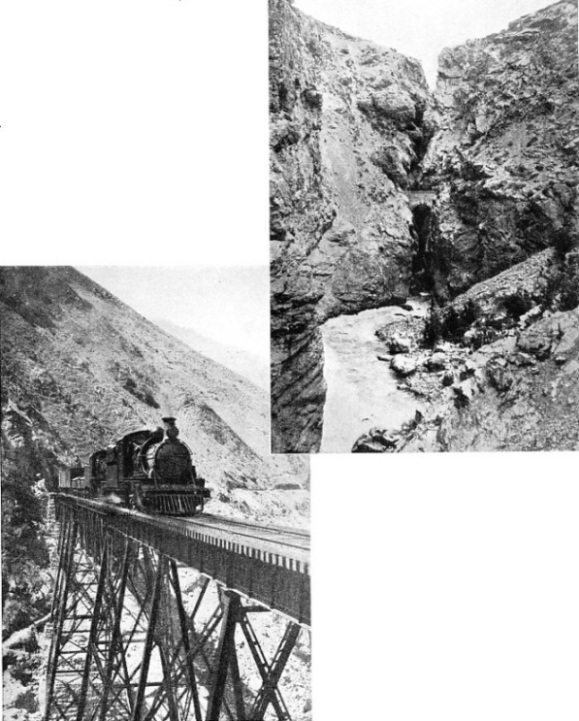

REMARKABLE ENGINEERING FEATS were accomplished when bridges were wedged between cliffs so that the Transandine Railway could be carried over mountain torrents. This picture shows the bridge at the “Soldier’s Leap”, almost dwarfed by the cliffs.

ANOTHER ENGINEERING TRIUMPH. The Challape Bridge, near Matucana, on the Callao-

This herculean task required immense preparations, for it was not possible to stop the traffic while conversion took place. In the company’s workshops at Mejillones 61 locomotives, 103 coaches and 2,140 wagons had to be reconstructed for the wider track -

Some of the steepest climbing, partly at 1 in 30, is immediately after the start from Anto-

From the nitrate region we now pass to that of copper. The Antofagasta Railway has handled up to a million tons of the former commodity in a single year; up a short branch just beyond Calama are the mines and smelting plant of the Anaconda Copper Company, which can deal with some 40,000 tons of ore and produce 600 tons of pure copper in a day.

At San Pedro, 197 miles from the start, are the great reservoirs, blasted out of solid rock, of the waterworks which supplies the city of Antofagasta, the nitrate fields, and all the railway stations up the line in this waterless country. Nearly £2,000,000 was spent by the railway on this project alone, and including the pipe lines from the mountains to the reservoirs, the water travels 235 miles in all from the source to Antofagasta.

We have now turned the 10,000 ft level, and presently the railway cuts through a lava bed over a quarter of a mile wide -

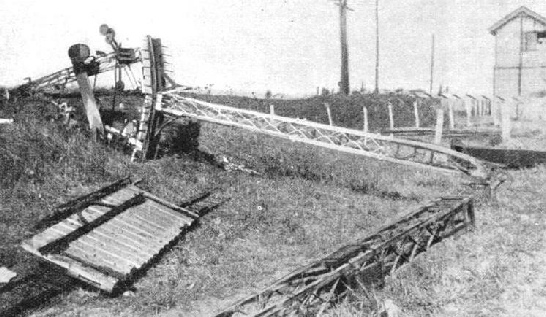

AT HIGH ALTITUDES the railway is exposed to the ravages of the cyclone. This illustration shows the effect of a storm on a signal standard on the Transandine Railway.

A little farther on, the railway skirts a lake, twenty-

From Ollague, 274 miles from Antofagasta, a branch is thrown off in a westerly direction to reach the rich copper mines at Collahuassi. Near Montt it reaches an altitude of 15,817 ft -

Proceeding from Ollague we cross into Bolivia and reach the important junction of Uyuni, where the line from Argentina, previously referred to, comes in from the south-

Proceeding from Ollague we cross into Bolivia and reach the important junction of Uyuni, where the line from Argentina, previously referred to, comes in from the south-

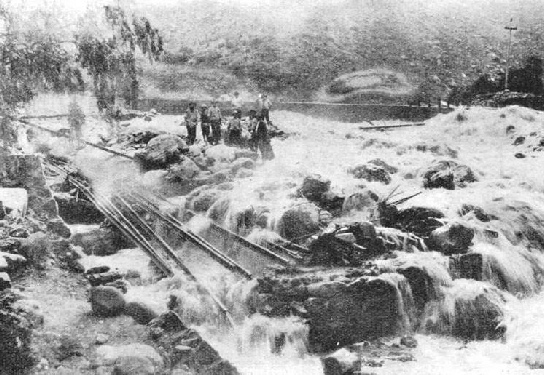

A SEVERE LANDSLIDE, which caused the Purhuay river to change its course in 1925 and flood the lines of the railway in Central Peru, caused a prolonged stoppage of traffic.

At Rio Mulato, 448 miles from Antofagasta, a branch is thrown off to the ancient city of Potosi -

The Bolivian section of the Antofagasta line now passes through many tin-

The city of La Paz, 12,143 ft above the sea, the virtual capital of Bolivia, has a dramatic rail approach.

Continuing the journey, we leave La Paz by the 60-

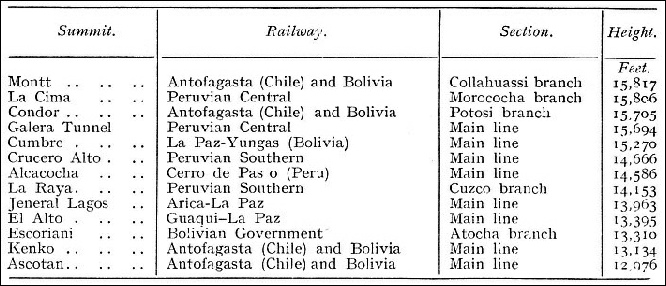

WHERE TRAINS MEET THE CLOUDS. A comparative table of the height of summits reached by the railway.

Sixty miles from La Paz we find ourselves on the shores of an inland sea. It seems almost incredible that a body of water of such enormous size can exist at a height of 12,500 ft, but here lies Lake Titicaca, perfectly real, and easily the largest sheet of navigable fresh water in existence at such an altitude. The railway-

Leaving the steamer at Puno, we find ourselves on one of the two trunk lines that Peru sends up from her Pacific coastline into the Andes. Both are on the standard 4 ft 8½-

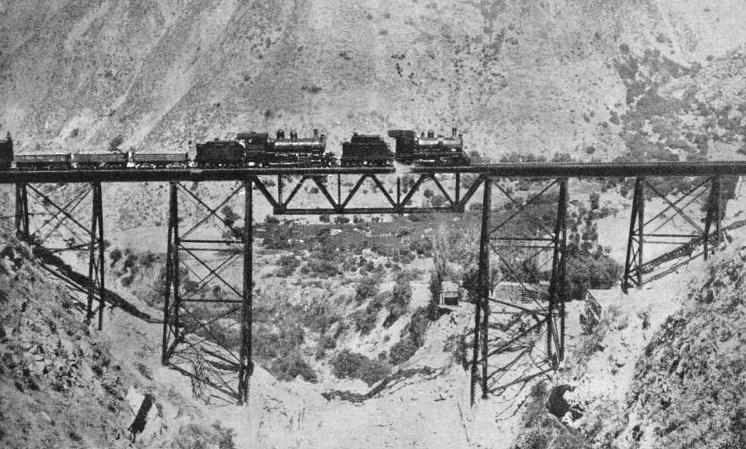

A DOUBLE-

Arequipa lies at the foot of three snow-

But the most remarkable of all the railways in the Andes is the one the description of which has been reserved until last. It is the Peruvian Central, which starts its course at Callao, on the Pacific coast, and in no more than 172 miles has climbed to the astonishing altitude of 15,604 ft at the Galera Tunnel. Of this ascent, 12,873 ft are crowded into the 118 miles from Chosica to the summit, which works out at an unbroken average of 1 in 48½. So rapid is the rise that it is necessary for the railway company to carry cylinders of oxygen in the trains, for the relief of passengers who may suffer from mountain sickness.

The steepest of the gradients on the Peruvian Central reach the very considerable inclination of 1 in 25, often for long distances together. Even then the only possible way of getting up the precipitous valleys on this side of the Andes is by means of zigzagging to and fro on the mountain-

Of bridges thrown across lateral gorges there are some amazing examples. Of these the most outstanding is Verrugas, which has a height of 252 ft above the chasm that it spans, and is 575 ft long. It is of a double cantilever type, supported on two trestle towers of steel, and replaced a previous structure that was washed away after a cloudburst. Ten miles farther up the line is the great Challape steel viaduct, also carried on spidery steel trestles. Longer still is Chaupichaca Viaduct, of a similar type, but 426 ft long, and including two very large lattice girder spans.

At last the train reaches Ticlio, which, at an altitude of 15,610 ft, is the highest station on any standard gauge railway in the world. Shortly afterwards it passes into Galera Tunnel, the highest point in which is 15,694 ft above sea level. The tunnel is 3,860 ft long.

From Ticlio the Marococha loop travels even higher, reaching at La Cima the record altitude for the standard gauge of 15,806 ft. This is the second highest railway summit in any part of the world.

Descending to Oroya, the Peruvian Central continues to Jauja and Huancayo, 346 miles from Callao, the last fifty miles, all at between 10,000 and 11,000 ft in altitude, being the finest wheat-

THE CACRAY ZIGZAG on the Central Railway of Peru. Piercing the sides of the mountains, and twisting and turning in great ravines, the train carries the passenger to some of the most lofty stretches of line in the world.

You can read more on “By Rail in the Argentine”, “Main Lines of Brazil” and “The Trains of Uruguay” on this website.

You can read more on “Across the Andes” in Wonders of World Engineering