© Railway Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

An “Ice Railway” Locomotive

A device that has revolutionised the lumber industry of North America

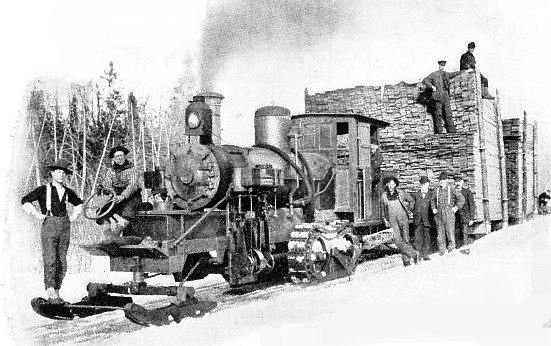

A HEAVY LUMBER TRAIN. A pilot sits on the front of the locomotive steering the leading runners by means of a wheel.

ALTHOUGH the ordinary steel highway is harassed and often disorganised completely by the forces of winter, owing to the locomotive being unable to drive its way through the piled banks of snow, there is a certain type of “railway” which is inoperative unless the ground is snowbound and frozen.

This is the “ice railway”. Strictly speaking it is not a railway, since the vehicles do not run along a pair of metals. But at the same time it demands a defined track, the pathway being two parallel ruts. The locomotive is a hybrid, being a combination of the railway engine, traction engine and steam-

The “ice railway” has undergone considerable development during the past few years. It was created to meet the requirements of the lumbering industry. In this field of human activity the conditions are somewhat peculiar. The removal of the enormous logs brought down by the woodsman bristles with difficulties. The lumber-

The result is that in the lumbering trade horses and oxen play a very important part in hauling the timber from forest to mill, and from mill to railway. The logs, balks, boards, or what not, are piled on heavy sleds. But the movement is slow; the capacity of the train load is limited severely by the number and strength of the beasts available. Moreover, animal traction is expensive ; difficulties arise in connection with foraging; while the cost of maintenance is just as heavy when traffic is at a

standstill as during periods of activity, because the creatures must be fed, and well too, to keep them fit for their arduous labour.

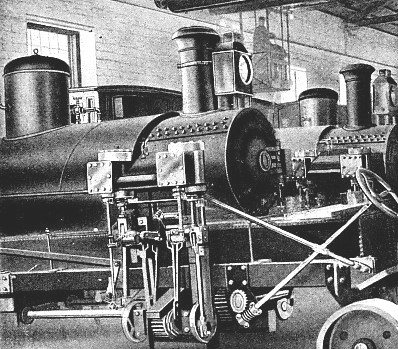

ONE ENGINE OF THE ICE LOCOMOTIVE. Showing inverted cylinders and power transmission. A similar engine is mounted on the opposite side of the frame.

Realising the shortcomings of animal transportation, the Phoenix Manufacturing Company of Eau Claire contrived a locomotive which could be run over an ice track as easily as its prototype can be driven over the steel highway. With infinite labour, and after innumerable peculiar problems had been solved, an engine was contrived and sent up into the forests of Wisconsin to prove its worth; to show how far it could compete with animal methods; and to determine the extent of its application.

The experiment was a complete success; steam haulage over the ice-

The ice locomotive revolutionised the situation. Bigger sleds could be built and loaded with three times as much lumber, while two or three such vehicles could be hitched to a single engine, which thus accomplished the work of 20 or 39 animals in half the time. The lumbering industries also discovered the significance of another item. The locomotive cost money only when it was performing useful service. When condemned to inactivity it did not “eat its head off”, as was the case with the animals.

The future of the ice locomotive was assured; the firm responsible for the creation found itself overwhelmed with orders. The engine was improved extensively as a result of experience acquired under practical conditions, and to-

The boiler, of the locomotive type, designed for a steam pressure of 200 lbs. per square inch, is 15 feet long by 36 inches in diameter, and is mounted upon a heavy reinforced channel iron frame. There is a large fire-

The engine is carried upon a leading “ bogie ” having a couple of massive runners. On the front of the engine is a large wheel, with a seat, so that steering is carried out upon the broad lines of the automobile. The driving or traction device recalls the caterpillar tractor. There is a heavy iron shaft, 4§ inches in diameter, which carries on each side of the engine two weighty steel runners. A pair of massive boxes in which runs a heavy steel sprocket wheel is attached to each end of these runners. The sprockets mesh with, and carry, a tread or lag chain, 12 inches wide by 14 feet in length, which, securing a purchase upon the road surface, propels the locomotive. On the inner side of the chain-

A BIG LOAD. The size of the stacks of sawn timber mounted upon each sled may be gathered from comparison with the crew.

The engine has four cylinders of 6¼ inches diameter by 8 inch stroke, two cylinders being disposed on each side, and bolted to the boiler and frame. Each pair of engines is fitted with link motion. The power is transmitted from the engine to the driving chains through a spur pinion mounted on the crank shaft, and a pinion mounted on the front end of the driving shafts. Bevel pinions are attached to the rear ends of these driving shafts, and these mesh with large bevel gears carried on the ends of the fixed shaft or rear axles. They also have spur gears, which transmit the power through the intermediate gearing to another spur gear mounted on the shaft to which the rear sprocket is keyed, this being the driven sprocket.

The locomotive is built on heavy lines so as to be able to withstand hard work. The cab fittings are of the usual railway locomotive type, with quadrant and lever for reversing. In running order the engine weighs about 19 tons, and with the steam pressure at 200 lbs. about 100 horse-

The vehicles themselves vary according to the prevailing conditions. If circumstances permit of the laying of a wide road, a gauge of 7 or 8 feet can be used to distinct advantage. The load stowed thereon may range from 10,000 to 20,000 feet. In such cases the over-

Successful operation is governed by the care expended upon the preparation of the road. A good track with easy banks and curves eases the strain upon the locomotive very considerably. When the snow has packed well and frozen hard, an excellent surface is offered, and the careful distribution of water over this surface, converting it to the semblance of a sheet of glass, especially in the ruts, enables heavy loads and good speed to be maintained with the minimum of wear and tear.

The work which can be accomplished by these powerful locomotives is astonishing. They may be seen puffing and snorting in the dense forests of the Middle and Western States and the backwoods of Canada. The heart of the Canadian lumber industry of Western Canada is around Prince Albert, where many of these little giants are at work. They may be seen toiling in a temperature ranging from 30 to 55 degrees below zero, drawing loads of 80,000 feet or more of green lumber over distances of 60 miles a day. Though the grades appear to be somewhat adverse, the train of seven sleds, large water tank, and caboose for the train crews, seems to make light of them. One lumbering firm in Minnesota, which has a 10-

At times these engines have to perform herculean work, especially when the country is swept by blizzards. Then the snow roads are buried beneath huge drifts, deep enough to swallow the engine. One firm had to hitch an improvised snowplough to the engine, and for 16 miles the train and crew had a stiff fight for every yard of the way. They turned round and found the snow had drifted just as badly, completely obliterating the road once more. It was another tedious drive over the 16 miles on the homeward jaunt, but the train got through, and only an hour or so behind her usual time. Some idea of the significance of this performance may be judged from the fact that on the railways traversing the self-

At another camp, the train comprising from 7 to 10 sleds, had to work continuously day and night over a track about 18 miles in length, the crews being changed at the end of each round trip. In this case the one engine did the work of 72 horses, and during the season handled 2,500,000 feet of pine, 100,000 posts, 3,000 railway sleepers, 200 cords of pulp-

Although this ice locomotive is virtually an asset of and peculiar to the North American continent, it has made its debut in Europe. An ice track has been laid down in Finland, and one of these imported engines has been put to work. This experiment is being followed closely by European interests, inasmuch as there is remarkable scope for such a system of transportation throughout the timber stretches of Russia and Siberia, where lumbering as an industry has achieved a higher stage of development than in the New World.

AN ICE TRAIN AT FULL SPEED. When the ice track is prepared carefully the train is able to make 8 miles an hour, with a load of 80,000 feet of lumber. On long journeys a water tank is attached to the engine.

You can read more on “The Conquest of Canada”, “Giant American Locomotives” and “Unconventional Locomotives” on this website.