Boiler-bursts are comparatively common in America. Here is described an interesting test of the efficiency of the Jacobs-Shupert boiler

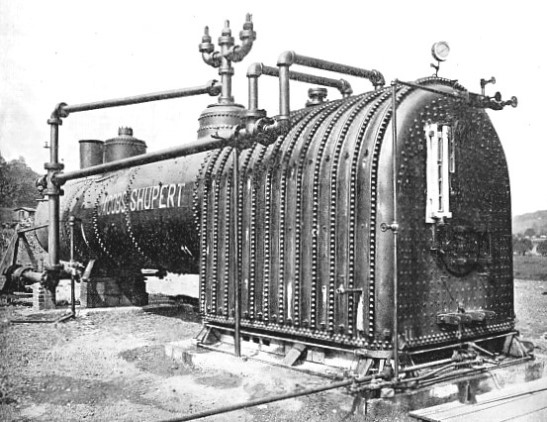

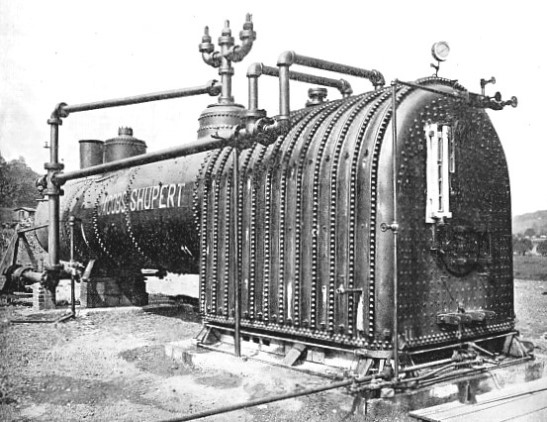

THE TWO TYPES OF BOILERS ready for the test at the trial grounds.

FORTUNATELY for railway travellers and others in Great Britain, the explosion of the boiler of a railway engine is a very rare occurrence, owing to the skill and care devoted to construction and maintenance, as well as to the thoughtful management of those responsible for its operation. But the United States present a very vivid contrast in this respect. There, on the average, a railway engine blows up once a week, and this class of calamity accounts for a long list of killed and maimed, as well as damage to the tune of several hundreds of thousands of pounds to property per annum.

Investigation invariably tends to attribute these disasters to one of two causes — a defect in manufacture, or gross mismanagement. Of course, in a few instances, even the most searching examination fails to offer a reason for the accident, but such mysteries are few and far between. Taken on the whole it is the penalty of carelessness which has to be feared the most, and in the direction of controverting this danger little has been possible of accomplishment by the railway companies, seeing that it turns upon the human factor.

The ordinary type of locomotive boiler is safe and reliable so long as it is handled with due care and thoughtfulness. Otherwise disaster swift and sudden is encountered. If the level of the water in the boiler is permitted to fall to such an extent that the roof or “crown” of the fire-box becomes uncovered, an explosion is inevitable. The fierce heat of the fire raises the temperature of the uncovered metal to such a degree that it loses its strength, cannot withstand the pressure of the steam within, and is driven inwards.

A certain amount of resistance to this internal pressure of the steam is provided by securing the crown sheet of the fire-box to the outer shell of the boiler by means of radial stay-bolts. So long as the water level is kept above the danger limit this security is adequate and the fire-box is held to its shape against the steam pressure. On the other hand, if through negligence or by oversight the crown of the fire-box is exposed to the fire, the stay-bolts become impotent, and are torn through the sheet, which then collapses.

Two American engineers, Messrs. Jacobs and Shupert, in the locomotive shops of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company, realising this weak feature of the ordinary boiler, endeavoured to design a type which would hold up against a low water level. After experimenting for several years they succeeded in their quest, and produced a boiler which is stronger and safer than those in general use. It was subjected to several tests and trials upon the railway, and, being found successful, has become widely adopted throughout the United States.

The Jacobs-Shupert Boiler

This Jacobs-Shupert boiler is built up in sections. The radial stay-bolts which hold the ordinary fire-box to shape are dispensed with entirely. Instead, there are a number of deep flanges, extending from the outer shell of the boiler to the inner shell of the fire-box. The shell of the latter is built up of a number of channel sections of arch shape, and these are riveted to the inside edges of the stay flanges. The adoption of the section secures exceedingly strong construction. Moreover, as the section is strongly riveted to the inner edges of the flanges, the crown sheet is able to withstand an enormous amount of pressure, which becomes distributed over a very great area before it can be wrenched free and driven in.

The inventors embarked upon a series of elaborate experiments to discover the behaviour of their boiler under low water conditions. Adjoining their Coatesville works in Pennsylvania an elaborate testing plant was set up in a field. The boilers were rigged up, charged with water, and then fired, the water being permitted to fall lower and lower until the crown of the fire-box was well exposed. Inasmuch as the boiler could not be stoked by a fireman in the usual manner, owing to the possibility of a blow-up, oil-fuel was used, being controlled from a safe distant point. In order to follow the falling level of the water as represented by the gauge, as well as to secure continuous readings of the steam pressure indicated upon its gauge, a bombproof shelter comprising a boiler laid on its side, and backed with baulks and earth, was erected some distance away for the accommodation of the observers. The readings were taken from this point by the aid of a telescope mounted on the roof of the bomb-proof shelter. Thus it was possible to follow the tests closely in perfect safety.

BLOWING UP. The ordinary boiler photographed at the instant the crown sheet collapsed. The Jacobs-Shupert boiler which passed the test successfully is alongside.

The numerous experiments made in this way fully confirmed the statements advanced by the inventors concerning the properties of their boiler, and the reduced liability, if not complete immunity, from accident ensured by the same when the fireman, through oversight or carelessness, permitted the water to fall somewhat low.

Finally, in order to secure an independent expert opinion, as well as comparative results, an interesting trial was carried out by Dr. William F. M. Goss, Dean of the College of Engineering of the University of Illinois, who is probably the greatest authority upon this subject in America.

In carrying out this test it was not only decided to submit the Jacobs-Shupert boiler to an unprecedented gruelling, but also to ascertain how far it was proof against explosion arising from low water conditions. Comparative results also were to be made with a view to ascertaining what the ordinary type of boiler could withstand in this connection, and also to determine whether, as had been maintained, a low water level was a positive cause of explosion.

For this purpose two full-sized locomotive boilers, such as are used for heavy express service, the one a Jacobs-Shupert and the other of the ordinary radial type, were set up in the experimental field. They were placed 50 feet apart, and the observer took up his position in the bomb-proof shelter placed 200 feet away. The fire-box end of each boiler faced the observer, and each carried a graduated water gauge and steam gauge, so mounted as to be seen readily through the telescope.

Each boiler was then connected to the feed water supply and set going until it reached the conditions which would prevail in actual express service. This was estimated to be equal to 1,400 horse-power, which would be sufficient to haul a fully loaded train at 60 miles an hour over a level road. At this juncture the feed water was cut off, but nothing else was touched.

EXTERIOR VIEW OF BOILER, with Jacobs-Shupert fire-box, immediately after low

water tests. Note blistering of paint on outside of fire-box, due to intense heat.

The Jacobs-Shupert boiler was tried first. The observers followed the falling water for 55 minutes, by which time, according to the reading of the gauge, it had descended 25½ inches below the crown sheet. It may have fallen to a lower level, but this was the limit of the gauge glass. During the first twenty-seven minutes the steam gauge indicated a pressure ranging between 215 and 225 pounds. At the lapse of this period the pressure gradually decreased until only one of 50 pounds was indicated. The test was discontinued after 55 minutes, because the small amount of water remaining in the boiler did not evaporate fast enough to ensure the draught necessary to maintain the fire. No sign of any failure was observed, and when the boiler was examined there was adequate external evidence of the severity of the ordeal through which it had passed. The paint on the outside of the fire-box was blistered, and a good deal had peeled off. It was evident that the crown sheet of the fire-box must have been brought to a red-hot condition under the fierce heat of the fire, but there was not the slightest sign that it had been weakened in any way by this extreme temperature, and it was apparently as fit for service, if required, as before the test.

The second boiler, of the radial stay type, was subjected to a test precisely similar to the foregoing in every respect, the feed water being cut off at an identical point. The steam gauge indicated a pressure varying from 200 to 233 pounds, and after it had been kept going for 23 minutes the water had fallen to a level 14½ inches below the crown sheet.

Then the crown sheet and the stays holding it in position had become heated to such a degree that they were wrenched apart, and the steam, at 228 pounds pressure, drove in the sheet. The steam rushed into the fire-box and there was a terrific explosion. Although the boiler weighed 40 tons, it was lifted off its seating, the fire-box was disrupted and fragments were blown in all directions. When examined, the boiler was found to be damaged so extensively as to require reconstruction.

This interesting test not only proved the efficiency of the salient features of the Jacobs-Shupert boiler, but also afforded convincing evidence that low water, with the overheating of the crown sheet, was a contingency beset with dire consequences, and probably is a common cause for a railway engine blowing up.

GENERAL VIEW OF THE TESTING GROUND. Showing the Jacobs-Shupert boiler in position, shelter for observers, and display board whereon spectators at a distance could follow the variations in the water levels and steam pressures during the trials.

You can read more on “Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company”, “Development of the Locomotive Fire-Box” and “Locomotive Accessories” on this website.