© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

Special Passenger Traffic

How the Railways handle Emergencies and Seasonal Crowds

LINING UP FOR LUGGAGE. A row of porters is waiting for the arrival of a train at Waterloo Station London. All the holiday “specials” have to fit in with the operation of the normal time-

AT least once a week the “service” or working time-

While exceptional freight movements, such as the handling of an “outsize” load, can usually be dealt with on Sundays or at other times when the pressure of general traffic is at its lowest, passenger “specials” almost always have to be fitted in when ordinary traffic is at its maximum. An example is the heavy Derby Day traffic of the Southern Railway, much of which has to be worked during the rush-

“Specials” are of every conceivable variety. They include the boat express which runs in connection with the arrival or departure of a particular liner (and which is not to be mistaken for the regular boat trains such as those between London and Harwich or Folkestone), race specials, Cup-

In earlier days, special trains were also often run for the conveyance of dispatches to a newspaper that wished to publish important information ahead of its rivals, but the telegraph and the telephone, and more recently wireless and the trans-

Many special runs of the past are of historic interest. Several of these were made on the Great Northern Railway in 1880, when that company put on a service between Leeds and London timed to cover the journey in either direction in three hours and three-

On one occasion during the year, the Royal special, conveying the Duke of Edinburgh, lowered this timing to three and a half hours, while on July 31, the Lord Mayor of London was brought up from York to London in three hours and thirty-

Another exceptional run with a Royal special was made on the London and North Western Railway, between Manchester and London, on May 4, 1887, when the Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VII) was conveyed over the 189 miles in 225 minutes. The running time was only 210 minutes after making allowance for stops at Crewe, Rugby and Willesden. Another special conveying the Prince of Wales, when he travelled from Liverpool to London on the occasion of the death of the Duke of Albany, took only 234 minutes, or 223 minutes if stops are deducted, for the 193½ miles.

A HOLIDAY RUSH This photograph was taken at the Southern Railway’s terminus, Victoria Station, London, and shows the crowds waiting for the seaside trains. Even in normal times, Victoria Station, with its seventeen terminal platforms -

But the most remarkable British achievement affecting Royalty was that of the Great Western Railway in July, 1903, when the 245½ miles from Paddington to Plymouth, via Bristol, were completed in 233½ minutes by a special train conveying the Prince and Princess of Wales, later King George V and Queen Mary, from London to Truro.

Some years previously -

The Coast-

Thirty years later a special was run in the opposite direction for a very different purpose. San Francisco had been virtually destroyed by a disastrous earthquake, and Mr. E. H. Harriman was hurried from Oakland to New York with plans for reconstruction. The time of 71 hours 27 minutes made by his special remained the coast-

The size of Great Britain makes impossible continuous runs approaching the length of that of the Garrett-

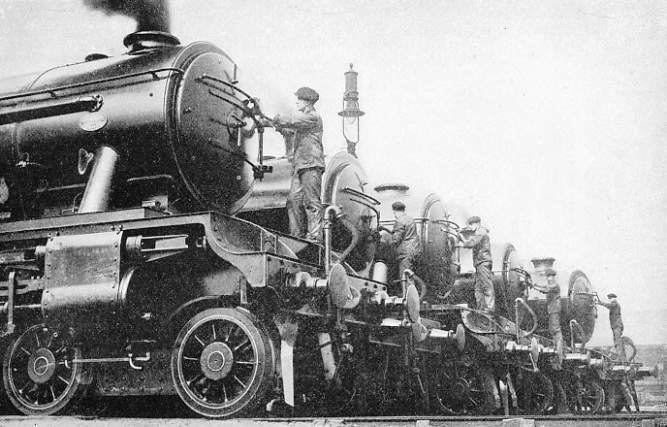

IN PREPARATION. A line of express locomotives at King’s Cross locomotive sheds, prior to hauling holiday passengers over the London and North Eastern Railway’s line. The engines are here seen being given a final polish before beginning their day’s work.

Another highly specialised form of traffic is the handling of military trains. Even during peace time this often involves the conveyance of artillery and limbers in addition to troops, while in war time it would necessitate the conveyance of immense quantities of munitions, rations, and stores of all kinds. Moreover, since such traffic has to be worked in accordance with the military exigencies of the moment, it is apt to involve the running on a large scale of special trains at short notice.

The magnitude of the task under modern conditions can be gauged by a few figures relating to two English railways -

National Emergencies

Between May 1, 1918, and the Armistice, Cannon Street Station was closed to public passenger traffic between 11 am and 4 pm daily from Mondays to Fridays, and from 3 pm on Saturday to Sunday midnight. The purpose of this arrangement was to enable the terminus to be used as an auxiliary goods station. It was employed on alternate weeks by Great Northern and Midland trains, engines and trains crews from these “foreign” lines being changed there. During the period of emergency working, 5,803 goods trains, representing a total of about 175,000 wagons, were dealt with at Cannon Street.

The South Eastern and Chatham was also called on from time to time to handle “extra special” military trains, which had to be available at any hour of the day or night, and which were run under what was known as the “Imperial A” code. The function of these trains was to convey highly placed personages, or even a single individual, who had to reach France in the shortest possible time. Both Dover and Folkestone were used as termini, and the sea journey was on occasion made by a special boat.

The usual make-

The London and South Western, serving Southampton, and thus forming the gateway to Havre, set up a colossal war record. Its traffic included 522,768 officers, 19,701,186 men, 1,447,148 horses, 11,208 guns, 112,278 road vehicles, 37,418 bicycles, 481,357 wagons of ammunition, baggage and stores, and 2,166 tanks. This traffic involved the provision of 58,859 loaded special trains, of which 10,175 were ambulance trains. It has been estimated that between the signing of the armistice and November 1919 at least another five million officers and men were carried.

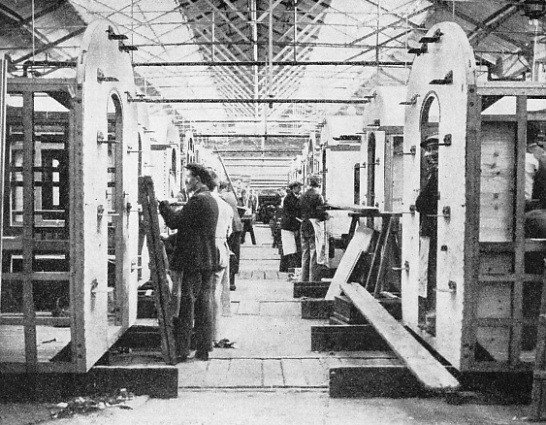

NEW COACHES FOR HOLIDAY PASSENGERS. Recently the Great Western Railway embarked on a building programme which includes some 200 passenger coaches and over 2,000 freight wagons. It takes about seven weeks to build a coach, and before the holiday season, the Swindon shops -

It is at Bank Holiday periods that special passenger working reaches its peak. Every Easter, Whitsuntide, and August Bank Holiday, and also -

It was once observed by a general manager of the London and North Western Railway that “a train service is like a house of cards; if the bottom card is interfered with, the whole edifice is disarranged and has to be built up afresh”. The phrase suitably describes the British railwayman’s task every Easter.

For the Grand National

It also describes the work of the operating department on an occasion such as the Grand National, when, in contrast to the Easter traffic, the bulk of the passengers have to be taken to their destination and brought back on the same day. This traffic is handled at three stations at Aintree, two belonging to the London Midland and Scottish Railway, and the third to the Cheshire Lines Committee, which is jointly controlled by the London Midland and Scottish and London and North Eastern Companies. There is also a special race day electric service worked by the Liverpool Overhead Railway, to which reference will be made later.

The intensive nature of this Grand National service can be gauged from the fact that between 11 am and 1.30 pm trains arrive at the rate of about one every two minutes, exclusive of the electric service, which runs in the “down” direction until just before 3 pm.

The special trains are worked from all over the country. On Grand National Day, 1934, the starting places included London (from Euston, St. Pancras, King’s Cross, and Marylebone), Carlisle, Workington, Preston, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Blackpool, Peebles, St. Albans, Newcastle, Nottingham, Bristol, Gloucester, and Market Harborough.

Every variety of rolling-

The stations, sidings, and locomotive sheds are, of course, taxed to their utmost capacity, and in this connection it may be mentioned that one of the London Midland and Scottish stations is used for passenger traffic only during the race meeting, no passenger services being worked into it during the rest of the year.

The Liverpool Overhead service deserves special mention. In 1905, a short spur line was built to permit through running between this railway and the Liverpool, Southport and Crossens electrified section of the then Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, and a through service was worked until 1922, when it was withdrawn as the result of road competition. But the through service is revived once every year -

Another sporting event responsible for an unusual volume of special traffic working is Doncaster Race Week in September, especially St. Leger Day. Traffic working is here complicated by the fact that while Aintree does not accommodate a heavy normal train service, Doncaster is a strategic point on the London and North Eastern, through which there passes the whole of its traffic between London and Scotland, as well as many local and cross-

The lay-

During the race week Doncaster handles also a very heavy horse-

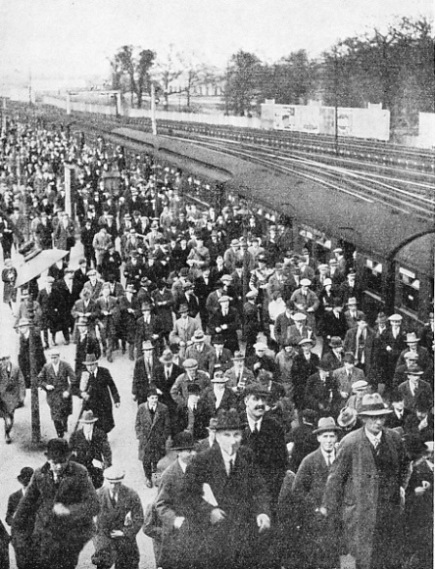

FROM ALL PARTS OF ENGLAND crowds pour into Wembley for the Football Association Cup Final. In 1934 the LNER ran thirty-

The Football Association Cup Final is another annual sporting fixture attracting much long-

A special feature of the Cup Tie traffic is the exceptional demand for saloon coaches, as many as three hundred being required on the LNER in 1934. Further, the bulk of the long-

One of the most remarkable instances on record of mass passenger transportation occurred in connection with the Coronation of King George V. On June 30, 1911, a Coronation Fête was given at the Crystal Palace to a hundred thousand school children, and in those early days of motor traffic the railway was called on to take all the traffic. This was another occasion when the special trains were required to be worked without interference with normal traffic, and five railway companies co-

The elaborate nature of the arrangements may be gauged from the fact that the special time-

An Unparalleled Feat

The problem here was complicated by the necessity for compressing the traffic within a relatively short working day, so that the children should have as many hours as possible at the Palace, and yet arrive home early. The first train -

This Coronation Fête traffic may be regarded as an unparalleled feat in railway transportation, and it is a tribute to the British railwayman to say that the performance was regarded as being all in the day’s work. That may, in fact, be taken as the railwayman’s motto. The organisation of a modern railway is extraordinarily flexible, and it must be, otherwise the “house of cards” would continually be in danger of disarrangement.

ANNUAL OUTINGS are an important feature in the railway’s special passenger traffic. This illustration shows hundreds of children at Liverpool Street Station, London, returning home after a visit to the seaside The task of carrying all these children is one of great responsibility; in many instances entire trains are run for the benefit of the children. In 1911 on the occasion of the Coronation Fête at the Crystal Palace, five railway Companies combined to convey 100,000 children.

As it is, special traffic is sandwiched in between the ordinary train service in a manner that is little short of miraculous. Even ordinary traffic may at times call for the utmost flexibility in working, as on the occasion of the late running of a boat train due to a bad Channel crossing. On the Southern; this contingency, which may occur at any time without warning, is partly provided for in advance by the existence of alternative “paths” or routes. A boat express from Dover may, for instance, be diverted for part of its run over the old London, Chatham and Dover main line via Canterbury, or from Ashford by way of Maidstone and Swanley Junction. But the Southern is fortunate in possessing an exceptional number of alternative routes from and to London.

Since Southampton has relieved Liverpool of some of its transatlantic passenger traffic, boat specials in England are more particularly identified with the Western Section of the Southern Railway. These trains are made up of the latest corridor stock, and now include Pullman cars in their formation. But “American specials”, which at one time were so prominent a feature of London and North Western express traffic, still run in and out of Euston.

In the past, these specials, which use the Riverside station at Liverpool, were booked to run the 192¼ miles to Liverpool (Edge Hill) without a stop, the composition of the trains varying in accordance with traffic requirements, but always including restaurant cars, and often special passenger stock. Now, however, boat portions for Riverside are usually attached to the ordinary expresses from London, and are detached at Edge Hill to run down to Riverside.

A considerable amount of miscellaneous ocean passenger traffic is also worked in and out of Euston. This does not normally require special trains, the passengers being accommodated in reserved compartments on ordinary expresses.

Special Working Notices

Mention of ocean-

The special working notices referred to at the beginning of this page are of more than one description, and include supplementary programmes of special trains covering a period of seven days, special train programmes which may deal with a shorter period, and fortnightly notices. A typical example of the first will deal with such traffic movements as short-

The fortnightly notice is so voluminous that a separate page would be required to do it justice. But it contains many important “miscellaneous instructions”, such as the notification of routes over which certain classes of locomotive may not run, and a list of passenger vehicles required for inspection by the carriage and wagon department. The whereabouts of these must immediately be notified to the Chief Operating Manager by wire.

Recent developments in one branch of special passenger traffic -

AN ELECTRIC INDICATOR to assist the traveller was introduced at Paddington Station by the Great Western Railway. The photograph shows the indicator, which was the first of its kind to be installed. It was erected in 1934 and is 30 ft long and 18 ft high. The indicator shows the scheduled arrival times, the delay -

You can read more on “During the Rush Hours”, “How Passengers are Handled” and

“Special Trains” on this website.