| Donate |

| FAQs |

| More on Railway Wonders |

| Other Series |

| Privacy & Terms of Use |

The “Flèche d’Or”

The “Golden Arrow”, Chemin de Fer du Nord of France

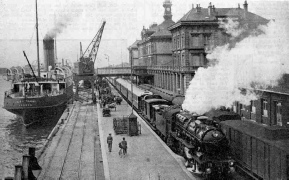

BOARDING THE “Golden Arrow” at Calais.

IT is a sure sign of growing public interest in railways that not only is the habit of naming express locomotives once again on the increase, but there is an outbreak of giving names to the “crack” express trains as well. And why not? It is much more exciting to look forward to a trip on the “Flying Scotsman” than a mere journey on the “10 a.m. From King’s Cross”, and there is no doubt that the choice of a suitable nickname for a present-

The train that is the subject of this article is barely a year old, but it is already world-

If, regretfully, we have to concede to our French friends the palm in the matter of speed, and, as we shall see presently, in the locomotive work entailed by the haulage of a train of this tremendous weight over the grades between Calais and Paris at such a rate, we can at least comfort ourselves with the reflection that, when our neighbours want to purchase the most comfortable coaches that money can buy they have to come to England for them. For you will find on each one of the magnificent Pullmans that make up the “Golden Arrow”, as you will on the sleeping and dining cars of the equally famous “Blue Train”, the name-

Long before we have actually moored at the Quay at Calais we shall have “spotted” the long train of cars, in the familiar Pullman livery of umber and cream, standing on the quayside awaiting its passengers. Lest we should make any mistake, we shall, find painted on the side of each coach two real golden arrows. In addition to this, each car carries its title in English and French -

RIGHT AWAY! The “Golden Arrow” leaving the Gare Maritime, Calais.

Ten Pullmans make up the total passenger accommodation of the ‘‘Golden Arrow”. As you will see in the photographs reproduced, they are longer than our English cars, and the interior view will show you that they are wider, too. Each coach is 77 ft in length over buffers and 9 ft 7-

The only other vehicle in the train is the peculiar-

Another privilege that is accorded to “Golden Arrow” passengers, in exchange for their extra fare, is that they do not have to pass through the “customs” but have their hand luggage examined on the train after leaving Calais. This enables the “Golden Arrow” to get away very quickly after the arrival of the boat. In fact, with this quicker start, passengers having left Victoria at 10.45 a.m. (or at 11 a.m., if they travelled by the second part of the boat train) can now reach Paris at 5.40 p.m., instead of at 8.15 p.m., which is the time of arrival of the remainder of the passengers.

Eleven vehicles, therefore, make up the “Golden Arrow”, with a total length, including engine and tender, of about one-

If we can teach the French how to build railway coaches, let it be said at once that they need to learn little from us in the matter of locomotive construction. We shall find one of the latest “Super-

Between Abbeville and Paris, for example, the “Golden Arrow” is only allowed 108 minutes for the distance of 109 miles, start to stop, and the outward bound 10 a.m. and 12 noon boat trains from Paris to Calais get 110 minutes in which to make the same journey, start to stop. The afternoon boat express, leaving Paris at 4 p.m., for Boulogne, is expected to run the 140½ miles to Etaples in 141 minutes. All these timings include a very severe slack, to 15 miles an hour, through Amiens.

In the north-

And what is the size and power of the locomotives to which the heaviest of these duties are entrusted? The “Super-

It is the compound principle on which they work that is the centre of interest in these Nord “Pacifies”. Although compound locomotive working has never taken a hold in this country, with, the exception of the familiar Midland compound 4-

It may be explained, for the benefit of any reader who is not quite sure what the word “compound” means, that the steam is carried direct from the boiler to one or two “high pressure” cylinders, in which it goes through a part of its expansive working; after that it is led on into two “low pressure” cylinders, where the expansion is completed.

The Nord engines are compounded on the “de Glehn” system, the two high pressure cylinders of which are seen, outside the frames, while the low pressure cylinders are inside.

It needs brains to get the best work out of a compound. The training of express drivers is carried, rather further in France than it is in this country, which furnishes in part, no doubt, the explanation of the extraordinary feats that the Frenchmen get out of their engines.

The design of the engines themselves provides the rest of the explanation. Each pair of cylinders has its own set of Walschaert’s valve-

THE “GOLDEN ARROW” AT FULL SPEED, near Villiers-

The fireman, too, has a strenuous task. In the first place the coal burned is of poor quality as compared with that to which our engines are accustomed, and is often in the form of “briquettes” or slack coal compressed into blocks. Then the firebox is exceptionally long and narrow -

But the hour of departure has now arrived and we must board the train. The timetable gives the start as “14.30”, according to the twenty-

It is a very difficult exit from Calais. From the Gare Maritime through the Town Station, for a distance of well over two miles, there are many sharp curves. Then, after a brief level run, the engine is faced, four miles after starting, with the beginning of the tremendous climb up the down-

By one of the rapid accelerations that are so common on the Nord, from the outskirts of Calais to the foot of the ascent to Caffiers we may expect to have attained anything from 50 to 55 miles an hour. Up the 1 in 125 speed will steadily fall, of course, but we shall probably top the summit at not far off 40 miles an hour. The upper stages of the climb may make it necessary for the engine to he worked in somewhere near full forward gear, in both high.and low pressure cylinders, with the regulator wide open as well. If we were on the footplate we should see that the boiler was finding all the steam necessary for this tremendously hard work, the needle of the pressure gauge remaining steadily at the 227 lb mark. In all probability the power exerted by the locomotive on this climb closely approach the figure of 2,220 horse-

Once over Caffiers Summit we have before us a 7-

From what we have heard about the French railways, we may think even 75 miles an hour to be something more than safe. But do not let us disparage the track of the Nord. Since the war a great deal of money has been spent in putting it into first-

In common with almost all Continental railways, the Nord uses a flat-

We dash through the Tintilleries Station at Boulogne, 26¼ miles from Calais, threading several tunnels as we skirt the eastern suburbs of the town, and then swing round to join the line from the Gare Maritime at the junction known as the “Bifurcation d’Outreau”. The speed round the curve will be rather higher, very likely, than that to which we are accustomed in England, but we need not fear that the driver is taking any undue risks, even though we do go over the junction at 50 miles an hour or so.

After 4½ miles of level running from the Outreau Junction, there comes a sharp rise of four miles to Neufchatel, and a corresponding descent of five miles to a point near Etaples. But now the engine has an easier length ahead. For the next 56 miles, through Etaples and Abbeville and almost to Amiens, the line is practically dead level, and it is along here that our engine and her crew will show their progress. Mile after mile will be ticked off at an even speed of 68 to 72 miles an hour, and an average of round about 70 -

At Amiens the direct line to the East of France and Switzerland, via Laon, leaves us on the left, and three miles later, at Longueau, we are joined on the left by the main line from Lille and Arras. Here we shall notice the extensive reconstruction works which have been carried out since the war, as this stretch of line represents the limit of the great German advance in 1918. After Longueau the engine is faced with a long climb, of all but 25 miles, up to Gannes. It is not steep; for most of the distance it is at 1 in 333, or almost exactly the same as the climbs on the North Western main line up to Tring, from both directions. In the last three miles, however, the climb steepens to 1 in 250. We shall forge steadily up to Gannes at a speed but little short of 60 m.p.h., and then down the corresponding descent to Creil speed will once again rule well up in the “seventies”, till we thread that station at a reduced speed of about 50 an hour.

We have now 31¼ miles left of our journey, and a little over half-

The only task now remaining is to muster up our best French, and go and congratulate the driver and fireman. To have worked a load some six times the weight of the engine over the grades that we have just recounted, with foreign coal, at an average speed of 58 miles an hour throughout, with due observance of the various slacks and no higher maximum speed than 75 miles an hour, is a feat indeed. And yet it is being done every day by the “Golden Arrow”.

You can read more on

“The Dover Pullman Boat Express”,

“The Northern Railway of France”

on this website.