Handling His Majesty’s mails at Seventy Miles an Hour

ROLLING STOCK - 2

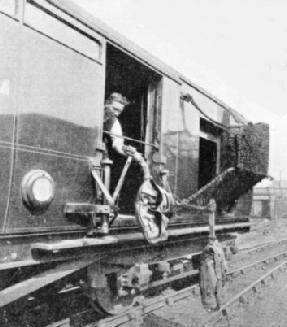

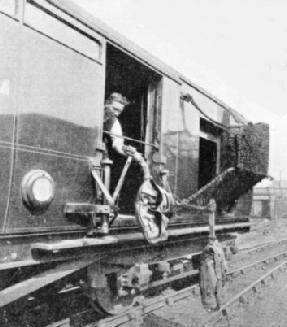

MAIL VANS are specially designed to deliver and pick up the postal bags when the train is travelling at high speed.

EVERY year the Post Office handles over 6,000,000,000 letters and 150,000,000 parcels. Eighty per cent of the letters, amounting to 25,000,000 bags, and 140,000,000 parcels, travel annually in British trains.

When the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was opened, in September, 1830, it was realized that the new mode of transport could be used with advantage for carrying mails, and on November 11 of that year the first dispatch of mails by train was made between these two northern cities. By July, 1837, Manchester and Liverpool had been brought, postally, within 16½ hours of London, partly by the use of the trains on the Grand Junction Railway, which had just been opened, and partly by coach.

But it was an invention, in 1838, which was destined to give the greatest impetus to rail transport of mails.

In that year the Grand Junction Railway Company, after some preliminary experiments made with a specially-fitted horse-box, built the first mail sorting-carriage on record. This coach, 16 ft long and 7 ft 6 in wide, weighing no more than 4 tons, was designed not only to carry the mails, but also to allow the contents of the mail-bags to be sorted on the route. The principal feature of the equipment was an apparatus that permitted the mails on the train to be exchanged with those brought to a line-side apparatus while the train was travelling at speed. John Ramsey, an officer attached to the Missing Letter Branch of the Post Office, was responsible for this, and received appropriate recognition by being appointed Post Office Inspector-General. Certain improvements to the apparatus were made in 1848 by John Dicker, an Inspector of Mail Coaches, but otherwise the equipment now in use is substantially the same as Ramsey's.

5,750,000 Miles of Mail

As the postal business grew, it became necessary to attach sorting coaches to more and more of the trains; these were usually the fastest over each main route, designated in the time-tables as “Mail”, and barred to ordinary passengers unless they were prepared to pay supplementary fares or to travel first-class. With the exception of two special postal trains, to which passengers are not admitted, these distinctions no longer obtain.

In Great Britain there are 73 travelling post-offices at work, each an independent unit, though many of these services inter-connect at junctions; 156 sorting-carriages are in use, and there are 132 stations with ground apparatus, where mail exchanging at speed takes place.

So that postal business shall not be disorganized by time-table alterations, many British mail-carrying trains come under a “controlled-mileage” system, whereby the railways, as part of their remuneration, must obtain the consent of the Post Office before any alterations are made in the schedules of the trains concerned. The aggregate now controlled is as much as 5,750,000 miles annually. Millions of bags are also carried in ordinary trains.

The basis of payment by the Post Office to the railways is a census of the actual number of bags carried in one test week, when every bag is specially weighed, and a total weight for the week, with the total mileage covered, is thus obtained. This is multiplied to obtain the estimated total carryings for the year, and this figure remains in operation until the next census. It includes allowance by the railways for assistance given to them by the Post Office.

Mention has already been made of two trains, specially reserved for the carriage of mails, from which the ordinary passenger is excluded. The Great Western Railway was the first company in Great Britain to run a special mail train, which worked between London and Bristol from February 1, 1855, for postal traffic only, until a first-class coach was attached for passengers from June, 1869, onwards. In later years, however, a special postal express ran - and still runs - nightly over the Great Western system in each direction between Paddington and Penzance.

But the most important of the railway postal services in the country is that which first ran, as a “special mail”, on July 1, 1885, between London and Aberdeen over the London & North Western and Caledonian Railways. This was a development of the “limited mail” introduced from Euston to Scotland in 1859, which included three sorting-carriages and three “mail-tender” vans, as well as limited passenger accommodation.

SUSPENDED ON A STEEL ARM, and enclosed in a leather pouch, the mail-bag is swept through the air at a mile a minute or more, to be caught in a net by the side of the track.

Officially known as “North Western TPO Night Down”, or “North Western TPO Night Up”, the “West Coast Postal”, to quote its more popular nickname, has now grown to large dimensions, and consists usually of thirteen capacious bogie vans. Six of these are sorting-coaches fitted with exchange apparatus, and the remainder are ordinary brake-vans, used cither for stowage or for parcels traffic. The only members of the railway staff carried on the train are the engine-crew and the guard; the Post Office is represented by an Assistant Superintendent, thirty-five sorters, and two porters. Five of the vans contain mail that has been previously sorted and is ready for delivery; the remaining eight, gangwayed together, form a wheeled post-office, which, throughout the night, will be a hive of increasing activity.

At seven o’clock in the evening the empty train is brought into No. 2 platform at Euston - an hour and a half before departure time. The sorters enter the empty vans. Already the red PO motor vans are arriving from all parts of London, converging on to the carriage-way at the side of the platform. The bags are taken out, quickly checked, and placed into the mail-vans.

Long before the train starts the work of sorting has begun; and by half-past eight, when the train leaves, the work is well in hand.

ATTACHING THE MAIL-BAGS to steel arms on the side of the van. The arms are made to lift up and swing inside the van, so that the postal officials can hook the bags on in safety. The collapsible net at the back of the van collects the mail-bags suspended from posts beside the line.

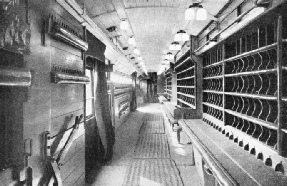

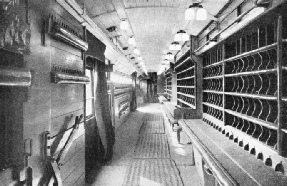

One of the principal scenes of activity is in the sorting-coach. It is 60 ft long and 8 ft 6 in wide, open from end to end, and with doors at the extreme ends leading to gangways that provide an open passage-way through the train. Down one side of it is a long counter. Above this counter an enormous rack is fixed, and this extends the full length of the coach. It contains hundreds of pigeon-holes, which receive the sorted correspondence. The letters are emptied from the sacks on to the counter. Part of this is in the form of a well to prevent rolled-up magazines and newspapers from rolling to the floor. Behind the sorters, along the other side of the coach, are long rows of pegs, on which will be hung the bags of sorted mail, ready for delivery.

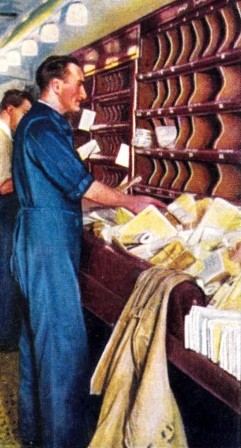

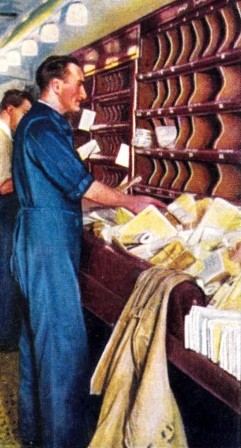

Perched on swing seats or, more often, standing on the swaying floor of the train, the sorters take the bundles of letters, read the addresses one by one, and pitch the letters fifty, sixty, and even seventy to the minute into their appropriate pigeon-holes. None of these pigeon-holes is named, and apart from one or two chalked reminders, the sorter has to remember that every number represents a district. Each sorter is responsible for a certain subdivision of the area dealt with in his coach.

Padded for Protection

Every precaution is taken to ensure that no accidents or mishaps should interfere with the work. The sorters must maintain a standard of physical fitness, as there is a certain strain involved in this work. So that the sorters shall not be injured should they be thrown off their balance when the train is rounding curves, all projecting corners and angles inside the coach are thickly padded. In order to reduce vibration to a minimum a special compound bolster type of bogie is used for the coach.

The first part of the sorting on the journey consists principally of “late fee” letters and mail which have arrived too late for sorting at the General Post Office. When this is finished there are the bags which come in at junction stations, by way of the exchange apparatus, while the train is travelling at speed. On one type of sorting coach there is a large net, made of stout rope, and held by a hinged steel frame folded neatly into a recess on the side of the coach. Just above the footboard of the coach, flanking each side of the main entrance doors, are four arms, known as “traductors”. These are hinged at the bases, and when not in use are secured in a vertical position against the coach-side. Outside the sorting coach, immediately above the footboard, is a row of lamps, which are used when the mail is exchanged, while the train is travelling at speed.

It is this row of lights along the side of the train that looks so picturesque and romantic as the “West Coast Postal” sweeps through the dark countryside in the small hours of the night. The transference of the mail by the apparatus requires considerable care and vigilance. The ringing of an electric bell is the first warning that the mail is to be transferred. One of the doors is rolled back, and the net opened out ready to receive the incoming mail. The rest of the staff stand clear while one man - whose duty it is to superintend the exchanges throughout the journey - stands by. In the darkness this man must know, more by sound than by sight, exactly where the train is running at any given moment, so that no mistake is made.

SORTING OFFICE. The interior of a mail van, showing on the right the long benches where the letters are sorted and the pigeon-holes provided to receive them. In the left foreground is the lever that is used to swing out the collapsible net into which the mail bags are delivered from track-side posts. Beyond this lever is the doorway through which the outgoing mail-bags are swung on their steel arms.

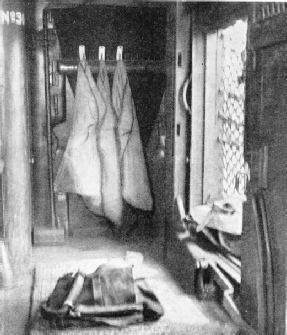

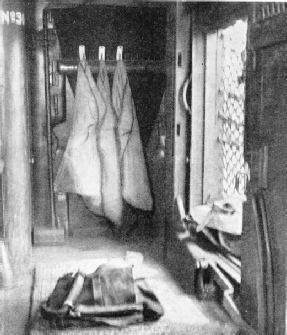

Two leather pouches shoot into the van through the open door and drop on to the floor. A lever closes both the net and the door. The bell ceases to ring. Inside each of the pouches is a bag of mail. Because of the buffeting that they receive the pouches are made of leather. Each bag weighs 20 lb, and must not contain more than 30 lb of letters, so that the complete unit weighs less than half a hundredweight.

Equal care and vigilance are necessary before the mail is pivoted into the van. The line-side apparatus consists of two tall rotating standards, with a stout ground-net alongside, the former for delivery to the train, and the latter for receipt of bags from the train.

The Warning

When he hears the approach of the “Postal” - signalled to him in his shelter by an electric bell from the nearest signal-box - the postman, who has strapped his bags tightly up in their pouches, mounts a ladder, and hangs the pouches from catches at the top of the standard. As the open train-net passes the standard, a strong leather-bound “V” rope at the top of the moving net knocks the pouches off the standard, straight into the net, which is cunningly designed in such a way as to deliver the pouches with a minimum of shock on to the coach floor.

SWEEPING PAST these posts at the side of the line the train collects the mail-bags in its extended net, delivering bags of sorted mail to the track-side net in exchange. The waiting postman who has brought the outgoing mail then removes the mail-bags containing letters for distribution in his own district.

At many points on the route a double exchange is made, mail being both delivered and received by the train. When mail is to be delivered, the bags for delivery are strapped into pouches. The main doors of the van are now opened, to enable these pouches to be attached to catches at the ends of the traductors, which are swung down from the vertical to the horizontal position, so that the pouches, held well out from the coach, are then dangling from the side of the train, ready to be collared by the ground-net. The moment the pouches have been knocked off by the line-side apparatus into the ground-net, the traductor arms, relieved of the weight, fly back with the help of springs to the vertical position.

Some of the consignments caught by the train are of considerable size. At Bletchley, where branch lines bring in the mails from the university towns of Cambridge and Oxford, four or five pouches come hurtling in, and at Nuneaton. six or seven: at both of these points the train is usually travelling at seventy miles an hour or more. At other places deliveries are as heavy, and even heavier; it is on record that one delivery of eighteen bags at Penrith, for the Lake District, required the use of the traductor arms on five sorting coaches along the train.

One of the most remarkable feats in connexion with the transference of mails arises out of the fact that the “West Coast Postal” does a certain amount of sorting for the “Irish Mail”, in order to relieve the two mail-vans which are run on the latter. Transfer from one train to the other is effected by delivering the bags from the “Postal” into the ground-nets at certain points, whence they are taken by the postal official on duty and hung from the standards, to be picked up by the “Irish Mail” as it flashes by a quarter of an hour later - and without stopping either train.

Eight Stops

Some of the exchanges, however, are too big to be entrusted to any apparatus, and it is necessary to stop the “Postal” at the principal junctions along the route - Rugby, Tamworth, Crewe, Preston, Carlisle, Carstairs, Stirling, and Perth - at each of which a postal staff is stationed to handle the avalanches of mail matter that pass into and out of the train. Through coaches for Edinburgh and Glasgow come off the train at Carstairs, and north of Perth the remaining portion of the thirteen-coach load which left Euston - now two vans only - has passenger coaches attached for the remainder of the journey to Aberdeen, which is reached at 7.35 am, just eleven hours after starting. None of the postal crew works right through. Some travel from Euston down to Crewe, and return the same night by the up “Postal”. The remainder work as far as Carlisle, where a fresh crew takes over, and returns with the up “Postal” on the following night. Such is the work transacted on what is probably the busiest train in Great Britain.

Mails have also to be handled by other railways in bulk, especially Continental and overseas mails, which specially concern the Southern Railway. Vast quantities of mail are dealt with at Southampton Docks, in particular, in connexion with steamer sailings to and from all parts of the world. When a liner from overseas is berthing, mail-vans for different destinations are standing in readiness on the railway lines on the quayside, with a powerful crane in attendance. The mails are swung out of the ship’s hold in large rope slings, dumped on the quay, and conveyed with such speed to their respective vans that the bags containing the important mails are usually able to leave by the first passenger “special” for London.

JUST ARRIVED. The mail-bags in the foreground have been snatched by the net from the line-side posts, and are ready for removal to the sorting benches. The stout leather pouches in which the bags are contained, for protection, are shot on to a mat on the floor of the van with considerable force.

In connexion with the calls made by transatlantic shipping lines at Plymouth, also, the Great Western Railway has perfected some clever appliances for the rapid handling of mails at Millbay Docks. The steam tender which meets the incoming liner off Plymouth is specially designed with large decks, free of all obstructions, to make possible rapid movement of mail-bags. On the quayside an automatic conveyer is installed. And as soon as the tender reaches the quay, bow first, the conveyer is swung round into position, and carries the mail-bags, with the help of an electrically-driven endless belt, direct into the railway vans, which are moved from time to time, as each one is filled, to bring another van opposite the conveyer. The record in rapid handling at Plymouth occurred when an incoming mail of 3,476 bags, weighing roughly 52 tons, was passed in 2½ hours from the tender into the train, including all the necessary checking and sorting of the bags. And so, in the carrying of His Majesty’s mails by the railways, as in all other railway operations, speed is the factor that counts, and it will be agreed that no stone has been left unturned to expedite mail-handling to the utmost possible degree.

Some mail trains are direct continuations of the mail coaches. The Irish Mails of the LMS, for example, succeeded the “New Holyhead Mail Coach”, which ran from “The Swan with Two Necks” in London by way of Birmingham and Shrewsbury to “The Eagle and Child” at Holyhead, crossing the Menai Strait to Anglesey over Thomas Telford’s famous Suspension Bridge.

A Five-Fold Speed-Up

Exactly a hundred years ago this coach journey occupied 27 hours - from eight o’clock one evening to eleven o’clock the next - and before steamships were invented sailing packets added anything from 17 to 20 hours more for the crossing of the Irish Sea to Holyhead. Not less than 48 hours were normally needed, therefore, for the through journey of the Irish Mails from London to Dublin. To-day, 100 years later, the same journey takes 9¼ hours, or less than one-fifth of the time.

ON THE RUN of the postal train from Aberdeen to London nearly a quarter of a million letters are dealt with each night. The average number of bags of mail received, opened and sorted over the whole run by the staff of about 50 men is 1,040 and the average number made up and dispatched is 920. Sorters are shown atwork in a mail sorting coach.

There are two Irish Mails in each direction - the Day Mail and the Night Mail. Both are arranged to leave Euston at 8.45 - the Day Mail at 8.45 am and the Night Mail at 8.45 pm. It is interesting to recall that when the Irish Mail made its first journey from Euston, on August 1, 1848, it started at exactly the same hour of 8.45 pm. But the Menai Strait was not then bridged by the railway, and the mails had to be transferred at Bangor from rail to coach for the rest of the journey to Holyhead, so that Kingstown was not reached till 11.30 am.

Considerable progress followed the opening of the Britannia Tubular Bridge in 1850, and it has steadily continued until to-day, when the Irish Mails that have left Euston at 8.45 pm are in Holyhead by 5.50 the next morning. The Day Mail is 25 minutes quicker, and reaches Holyhead at 5.25 pm, and Dublin at 6 pm.

Both of these trains carry passengers. Restaurant cars are attached to the Day Irish Mail, while the Night Mail has sleeping cars. Two postal vans are attached to each service, and exchanging of mails goes on throughout the journey.

When the Irish Night Mails reach Holyhead, or Dun Laoghaire, as it is now called, three Irish sorting-coaches are waiting on the quay, each with through passenger carriages attached. One is going down south to Cork; the second is travelling across to Galway; and the third is to make its way northwards over the frontier from the Irish Free State to Belfast.

Some curious cross-country journeys are made by several of the mail-trains in Great Britain. At seven o’clock in the evening a passenger train leaves Newcastle-on-Tyne for the South, and attached to it is a string of postal vans, including sorting-coaches, painted in LMS colours, but bearing the mysterious legend, on each coach, “M & NEJPS”, which must have puzzled many observers. The interpretation is “Midland & North-Eastern Joint Postal Service”. It was a service established in pre-grouping days by the Post Office, in agreement with the Midland and North-Eastern Railways, to run from Newcastle through York, Sheffield, Derby, and Birmingham to Bristol, and similarly in the reverse direction; and it still continues under the old title. Passengers are also conveyed by this train, which forms a most valuable postal link between the North-East Coast and South-West England.

SORTING THE LETTERS continues unceasingly during the run. Those which are not transferred by the mail exchange apparatus are dropped into large postal sacks, to be collected by motor vans at the railway termini.

Among other unusual routes taken by postal sorting-coaches there is one from Lincoln through Nottingham and Derby to the High Level Station at Tamworth, where the bags are dropped down a chute to the Low Level platforms, to be transferred to the “West Coast Postal”. From York, connecting with the Newcastle and Bristol service just mentioned, a sorting-coach attached to ordinary passenger trains makes a cross-country journey through Leeds, Huddersfield, Stockport, and Crewe to Shrewsbury, making important connexions throughout its journey. Newcastle is connected with Ireland by a postal van which runs along the border to Carlisle, and then through Southern Scotland to Stranraer, whence the mails are taken by water across to Larne and on to Belfast.

The Human Factor

All these main and subsidiary postal services have been evolved in a ceaseless endeavour to speed up internal communic-ations. Great success has been achieved by the travelling post offices, but it is a success that has been hard won. The staff, working at speed in confined spaces and within rigid time limits, has always to cope with an ever-varying influx of letters and packets.

In the few moments between stations the sorting and dispatching goes forward continuously, and works as smoothly as the running of the train itself. The system demands untiring efficiency and alertness. There is not a spare moment on the whole journey.

The success of the “TPOs” - as railwaymen call them - is widely acknowledged. That success is due not only to the excellent organization of the department, but also to the human factor - the men of the TPO’s.

You can read more on

“Carrying the Mails”,

“The Post Office Railway” and

“The West Coast Postal”

on this website.