A Famous Train of the LMS

FAMOUS TRAINS - 33

No. 5999 “Vindictive”, one of the re-built Claughtons referred to in this article. A notable feature of this re-building is the manner in which a considerable increase of power has been obtained with an enhancement, rather than any loss in the symmetrical appearance of this particularly handsome engine.

No. 5999 “Vindictive”, one of the re-built Claughtons referred to in this article. A notable feature of this re-building is the manner in which a considerable increase of power has been obtained with an enhancement, rather than any loss in the symmetrical appearance of this particularly handsome engine.

IN olden days this train was called the “Wild Irishman”, though the London and North Western authorities at Euston may never have given official recognition to so stirring a title, that the expresses to and from Holyhead have ever been distinguished by exceptional speed, although doubtless at the close of last century they were among the fastest trains then running. Nowadays, however, their rates of travel are surpassed by those of fast trains in other directions, and the timings along the North Wales coast, indeed, are slower by nearly 10 minutes than once they were. So the more sober title of “Irish Mail” doubtless suits the subject of our study well enough.

Various express services on the LMS system give direct connection to Ireland. The “Ulster Express”, for example, provides the main service from London to Belfast and the North of Ireland, and another service to Belfast is afforded through Liverpool by the 5.55 p.m. “Merseyside Express” out of Euston. The principal Irish mails are all carried via Holyhead, however, and from there across the sea to the port near Dublin that was once called Kingstown, but which the Irish Free State authorities now prefer to designate “Dun Laoghaire”, in their Erse tongue. Pronounce it “Dun Lairy”, and you will not be far off the mark.

At one time there were three independent steamer services plying between Holyhead and Ireland. The City of Dublin Steam Packet Company carried the mails from Holyhead to Kingstown; the London and North Western Railway ran their own service up the Liffey into North Wall Station in Dublin; and another service, for the North of Ireland, was run by the railway from Holyhead to Greenore. The last of the three vanished early in the war, and was never revived, in view of the ample facilities provided by other routes. Then the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company lost the mail contract, and with it the chief financial reason for its existence, so that it promptly went out of business. This left the field to the railway, and the London, Midland and Scottish, as it had now become, diverted the North Wall service to Dun Laoghaire, which has splendid facilities for dealing with the traffic, and put into commission some splendid steamers, of large passenger capacity.

All the LMS passenger steamer services between England and Ireland have now come down to three - between Holyhead and Dun Laoghaire, whence through coaches run to Cork, Galway and Belfast, serving almost the whole of Ireland; Hey-sham and Belfast; and Stranraer, for Scottish passengers, and Larne, just to the north of Belfast. This admirable concentration has made possible great economies in working.

Except during the summer months, it is only on the Holyhead route that both a day service and a night service are run. There are therefore two “Irish Mails”, one leaving Euston at 8.30 in the morning, and the other at 8.45 in the evening. In the opposite direction the times of arrival in London are exactly the same, 5.50 a.m. for the night mail and 5.50 p.m. for the day mail. The night train generally carries considerably the larger number of passengers - coming Londonwards I have known as many as 17 bogie coaches, including sleeping cars, pull out of Holyhead - and so provides the bigger proposition of locomotive haulage; but as we shall doubtless want to see all that we can, the day “Irish Mail” is probably the better for our purpose. So we must present ourselves at Euston shortly after 8 o’clock in the morning, and if the early departure from home has deprived us of our breakfast we need not worry about it, as the restaurant car staff on the train will be happy to make good the deficiency.

The “Irish Mail” varies considerably in weight according to the season of the year. Next the engine are two or three vans, including the Post Office sorting tender; then follow several third-class coaches, a set of three restaurant cars - third-class, kitchen and first-class - and a first-class compartment coach and brake, or a combined first-class brake, making up ten or a dozen vehicles or more in the Holyhead portion. In all but the summer months the lighter formation of the Irish section allows of the addition, as far as Rugby, of a portion for Manchester, consisting of two or three corridor coaches; but in the height of the tourist season the Manchester train is run separately from Euston at 8.40 a.m. The main train also gives a good connection from Crewe to Liverpool, so that it is generally well filled on its journey.

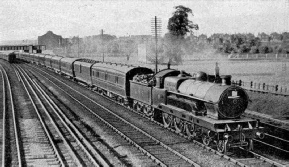

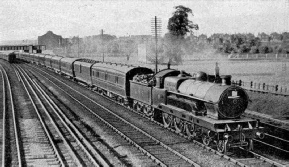

The up “Irish Mail” running at speed. The engine is one of the original Claughtons.

It is now frequently the custom, in these days of lengthy continuous locomotive workings, to run the engine of the “Irish Mail” through from Euston to Holyhead, and as the “Royal Scot” 4-6-0 engines are too heavy to work along the North Wales line, and especially over the Conway and Menai Bridges, the “Claughtons” are usually entrusted with these duties. It is for these workings in particular that a number of “Claughtons” have recently been transformed into some of the most handsome 4-6-0 locomotives in the country, by the substitution, for their original 5 ft diameter boilers, of new 5 ft 5-in, boilers, pressed at 200 lb per sq in instead of the previous 175 lb. As compared with the clumsy external appearance of the “Royal Scots”, indeed, the rebuilt “Claughtons” are a striking witness to the fact that it is still possible to develop locomotive power without an entire sacrifice of the grace of locomotive line.

The “Claughtons” have had a chequered history, having been notoriously variable and uncertain in the quality of their performances. Some of the early feats that I recorded behind No. 2222, “Sir Gilbert Claughton” - the first of the type - under the able guidance of old John Ford, one of the best-known Crewe drivers of his time, I have never surpassed with a “Royal Scot” or any other type of locomotive on LMS metals. Of these the most astounding was a start one evening out of Oxenholme, in the Westmorland Fells, with a 310-ton train, which No. 2222 ran from the dead start right up to Shap Summit, 915 ft above the sea, in 23 minutes, 11 seconds for the 18⅝ miles, attaining 48½ miles per hour up the steep ascent to Grayrigg, touching no less than 75 on the short level stretch thence to Tebay, and mounting the last four miles at 1 in 75 to Summit, at a minimum rate of 38 miles an hour. This was running, indeed!

In those early days the “Claughtons” were allowed to take trains of 440 tare tons without assistance, but in recent years it has been necessary on the faster trains to cut that figure by 80 tons. It is to be hoped, however, that the performance of the enlarged “Claughtons” will be in keeping with their magnificent appearance. In locomotive work, “hand-some is as handsome does.”

We have twice previously travelled over the LMS main line between Euston and Crewe in these articles - once on the “West Coast Postal” express and again on the “Royal Scot” - but for the sake of new readers a brief re-capitulation of the main features of the route will be forgiven, and may, indeed, stimulate our memories. The first handicap is a rise at between 1 in 70 and I in 105, beginning practically from the end of the platform at Euston. The engine that brought in our empty coaches will assist by giving us a friendly shove in the rear up to Camden - an incline which, in the early days of the London and Birmingham Railway, was worked with wire ropes! As we are passing on the left the capacious Camden locomotive sheds - with their lines of engines of all types - “Royal Scots”, “Claughtons”, “Princes”, “Georges”, Midland compounds, “Moguls”, and others down to the villainously ugly six-coupled saddle tanks that Crewe produced long ago for shunting purposes - our “banker” will quietly drop off the rear and we shall carry on without assistance.

Between Camden locomotive sheds and the mouth of Primrose Hill tunnels there is one of the most wonderful - possibly - indeed, the most wonderful - layouts of railway track in the country. Unfortunately the major part of it is hidden from view underground. When the electrification scheme of the late London and North Western Railway was extended into Euston and Broad Street, the problem arose as to how the electric trains, which were to run over the northernmost of three pairs of tracks from Willesden to this point, could be got across to the centre two of four tracks for their descent into Euston terminus, without fouling all the other traffic. In fact, looking from south to north, up and down fast lines, up and down slow lines, and up and down electric lines had to resolve themselves into (in sequence) empty carriage lines, down fast line, down electric line, up electric line and up fast line into Euston; down and up lines for Broad Street; and connections to Camden goods yard in between. A Chinese puzzle, indeed! But it was successfully solved and, by a maze of lines, many of them in tunnel, the whole of these train movements can be accomplished practically without any crossing by one train of the path of another. The reconstruction was, of course, an enormously costly business.

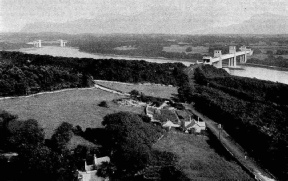

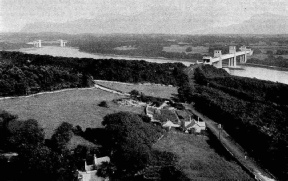

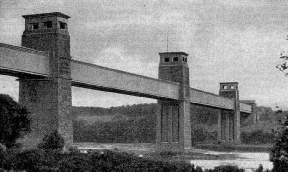

View of the Menai Straits from the Anglesey side, showing the Britannia Tubular Bridge on the right and the Suspension Bridge in the distance on the left.

Meanwhile we are hurrying along to Willesden Junction, and 10 or 11 minutes after our departure from Euston at 8.30 a.m, we may expect to halt in the Low Level Station at Willesden, 5½ miles distant. The Willesden stop is a relic of bygone days. Formerly practically every down London and North Western express called at Willesden to pick up passengers from the suburbs who had been brought in by connecting trains; and every up express also stopped for the purpose of ticket collection.

But nowadays, to save time, and also because the majority of suburban passengers prefer to join the train at the starting point of the journey, thereby getting a better choice of seats, the Willesden call is a rarity. On the down day “Irish Mail” however, it is still preserved, as well as on the following 9.0 a.m. and 9.10 a.m. down Birmingham expresses, for the benefit of suburban people wanting to join the train. Only a brief stop is necessary, and at 8.43 a.m. we are away again on our 77-mile run to the next stop at Rugby.

This is an easy stretch. Throughout its length we pass over no gradient steeper than 1 in 330, the summit points being Tring, 31½ miles out of Euston; Roade Cutting, 60 miles; and Kilsby Tunnel, about 77 miles distant. The line rises at this inclination all the way from near Wembley to Tring, save for a short level stretch from Carpenter’s Park, just before Bushey track-troughs, to Watford Tunnels; then it falls most of the way from Tring to Bletchley, at this and easier grades. Following a level stretch from Bletchley to Castlethorpe, where are situated the second set of troughs, is a similar but shorter rise to Roade Cutting; and from there the line is fairly level through Blisworth to Weedon, whence ensues a third rise to Kilsby Tunnel, and a drop to Rugby.

Such gradients are too flat for high speeds with heavy trains. We may touch 60 m.p.h. at Watford, 70 or a shade over between Cheddington and Leighton, and a little over 60 at Weedon; while the three summits should be breasted at round about 50 m.p.h, or possibly a little less at Tring and a little more at Kilsby. The allowance of 84 minutes from Willesden to Rugby ought to be observed with ease, in the proportion of 31 or 32 minutes for the 26 miles front Willesden to Tring, 14 minutes for the 15 miles on to Bletchley, 14 minutes for the 13 miles from Bletchley to Roade, and 24 or 25 minutes for the last 23 miles into Rugby.

We are due away from Rugby at 10.11 a.m, the next stop being at Crewe, For this distance of 75½ miles the timetable allows 85 minutes, inclusive of a long slowing round the Trent Valley curve at Stafford, and the possibility of being slowed, too, on account of subsidences caused by colliery workings under the line at Polesworth, near Tamworth. Shortly after re-starting, the engine takes a third draught of water from track-troughs just beyond Rugby. For many miles there is little worth mention in the matter of gradients. A gentle rise to Shilton is succeeded by falling grades most of the way to Tamworth, with a level intervening strip from Nuneaton to Atherstone; and we may expect to touch 70 miles an hour at both Nuneaton and Polesworth. Between the latter station and Tamworth there will probably be a slight slowing at least through the colliery area previously referred to.

At Hademore, between Tamworth and Lichfield, there lie ahead the fourth set of track-troughs, prior to a 1 in 330 ascent that extends through Lichfield to Armitage. It will be noticed that along the West Coast main line of the LMS the authorities have contrived to lay their troughs at roughly equal spacings of 30 to 35 miles apart, which arrangement accounts for the limited size of tender in use with LMS express engines, rendering possible substantial economies in ton-mileage.

The ornamental entrances to Shugborough Tunnel should be noted as we hurry through Shugborough between Rugeley and Stafford. Brakes then go on for Trent Valley Curve, and we pass through Stafford at 40 miles per hour. From Rugby we shall have taken about 18 minutes for the first 14½ miles to Nuneaton, then 12 or 13 minutes for the 13½ miles to Tamworth, according to the severity of the Polesworth slack. The 13¾ miles from Tamworth to Rugeley may be expected to occupy 15 minutes and the 9¼ miles on to Stafford 10 minutes, making 55 or 56 minutes for the 51 miles from Rugby. There is now a long and gentle ascent for 14 miles ahead to Whitmore, which should not take more than 17 minutes, and we shall then have 12 or 13 minutes in hand for the 10½ miles of downhill into Crewe. This includes three miles at 1 in 177 - the steepest gradient between Camden and Crewe - on which we may get up to as much as 75 miles an hour at Betley Road - ere the long and severe slowing, through the immense South Sidings and past the South engine-sheds, which precedes the stop in No. 1 main down platform of Crewe Station. At Whitmore, by the way, we passed the fifth set of track-troughs, which are of particular interest in that they were the first track-troughs in any part of the world when John Ramsbottom, then Locomotive Superintendent of the late London and North Western Railway, laid them down as an experiment, in 1859.

The platform at which we are stopping in Crewe is not the longest in the country, but it makes a good bid for supremacy, being 1,509 ft in length. We are booked to halt here from 11.36 to 11.48 a.m, as important connections are made at Crewe, and a good deal of mail matter has to be dealt with. On leaving, we shall have to divide our attention between the fleet of engines of many different types standing outside the North engine-sheds, on the left, and the remarkable suspension bridge on the right, which clears a tremendous width of tracks at one bound, and gives access to the Crewe locomotive works. Glimpses may be caught also of some of the numerous avoiding lines which, by skilful tunnelling, keep clear of the passenger station the whole of the vast freight traffic that passes through Crewe, from no matter which direction it comes - the main line, the Shrewsbury line and the North Stafford line on the south, and the north main line, the Manchester line and the North Wales line on the north. It is through the centre of the locomotive works that we now pass - the works that have created the town of Crewe, with its 45,000 inhabitants, and at which it has been said that everything needed by a railway is made, from finished locomotives to wooden legs for such of the staff as are unfortunate enough to lose them in accidents! This does not include, of course, the carriages and wagons, for the former of which the late L & NWR established works at Wolverton, and for the latter at Earlestown.

A fine photograph showing the up “Irish Mail” passing Kenton.

It is but a short level run of 21¼ miles from Crewe to Chester, and for this the timetable allows 27 minutes. When the night “Irish Mail” runs in duplicate, the first portion is booked to run non-stop over the 179¼ miles from Euston to Chester, and the summer “Welshman”, leaving Euston at 11.10 a.m, goes one better by covering the 205½ miles from London to Prestatyn without a stop. But even this feat has been beaten by the first portion of our own train which, on four Saturdays during the past summer, left Euston at 8.25 a.m. and ran without any stop over the 263¾ miles to Holyhead, arriving at 1.41 p.m, at an average of 50.3 m.p.h.

Important connections from both Liverpool and Manchester are made at Chester, which bring in so much traffic that during the height of the summer a relieving train is run ahead of us from Chester to Holyhead, and we do not pick up passengers. For the Chester stop eight minutes are allowed - from 12.15 to 12.23 p.m. - ere we leave on our final run of 84½ miles to Holyhead. At one time the “Irish Mail” was booked to cover this distance in 93 minutes, but the time since the war has been considerably eased out, to 102 minutes.

There is a 1 in 200-336 down-grade out of Chester, which gives us an excellent start to Sandycroft; after this the line is as near perfectly level as makes no matter for the next 31 miles. The first of the Welsh mountains begin to appear on the left-hand of the train, but we soon come out to the coastline of North Wales, which we are now to hug very closely for more than twice the distance just mentioned. The proximity of the sea, however welcome it may be from the scenic point of view, is not an unmixed blessing to the railway. After we have passed Rhyl, 30 miles from Chester, and have mounted 2½ miles at 1 in 412 and a mile at 1 in 100 from Abergele - scene of a frightful disaster to the “Irish Mail” in 1867, when a collision with a train carrying oil and the fire that followed caused the loss of 33 lives - we cross Llandulas Viaduct. In a later year an exceptionally high tide and a very rough sea encroached inland and swept away this viaduct completely. A temporary line with a gradient of 1 in 23 was laid down to the bottom of the valley and up the other side, to bridge the gap, and to the credit of Crewe Works be it said that a new viaduct of seven steel spans was designed, the material was rolled, the girders were assembled and conveyed to the site, and the structure was complete and in use, within a single month of the accident! Further on, too, near Penmaenmawr, the line was breached by the sea in 1899, and two lives were lost by the derailment at the spot.

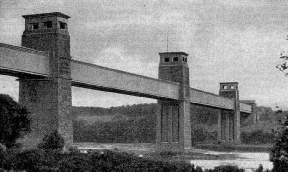

For the level stretch from Chester to Rhyl, 30 miles, we shall take 34 minutes or so; then follow 14¼ miles of undulations past Abergele and Colwyn Bay to Llandudno Junction, which occupy 17 minutes more. Through Llandudno Junction there is a speed restriction. The line then swings across the Conway River by means of a tubular bridge of considerable span, which provides a foretaste of the much bigger Britannia Tubular Bridge, over which we shall pass presently. At the further end of the Conway Bridge we pass right through the walls of Conway Castle, and are soon again running high above the water round the margin of the Penmaenmawr Mountain, with its busy granite quarries, between Penmaenmawr and Llanfairfechan. Rising on a moderate grade from Aber, first at 1 in 163 -20 and then at 1 in 660, we hurry through Bangor, 59¾ miles from Chester, in about 69 minutes from the start.

A mile-and-a-half beyond, at Menai Bridge, we curve sharply northward in order to leave the mainland of North Wales for the island of Anglesey. The Menai Straits at this point are 500 yards in width, and Robert Stephenson, who engineered the route, devised the Britannia Tubular Bridge in order to span the obstacle. Two continuous rectangular tubes, each 1,510 ft in length and 4,680 tons in weight, have been set up side by side, supported both at the ends and by three intermediate towers; the down trains run through the middle of one tube and the up trains through the other. It is a singular experience to plunge into the darkness of the tube just when one might be expecting to have the most extensive of views.

The famous Britannia Tubular Bridge, which plays an important part in the run of the “Irish Mail”.

Immediately on the other side of the bridge lies the famous Welsh village that rejoices in the name of “Llanfairpwllgwyn-gvllgogerychwymdrobwl-llandisilio-gogogoch”! It has a station, but the authorities, despairing of obtaining a station name-board that would not overlap the platforms at both ends, have wisely cut the name down to Llanfair, and left it at that! Thence we hurry across the island, past Gaerwen, junction for Red Wharf Bay and other delectable resorts on the north side of Anglesey; down a dip of three miles steepening from 1 in 264 to 1 in 100, which may carry us well into the “seventies” by way of maximum speed; up the other side, and finally down falling gradients until we can sight the port of Holyhead dead ahead.

Into the commodious harbour station we run at 2.5 p.m, 263¾ miles from London, and 5 hours, 35 minutes after leaving. Across the quay lies the steamer for Ireland, and the transfer of passengers, mails and baggage is quickly effected. Later on we, too, must pay a visit to the “Emerald Isle” and see how its railways conduct themselves - wonderfully well, let me say in advance, with excellent trains and remarkably high speeds. But that is a subject we must leave for another time.

The up “Irish Mail” at Kenton, double-headed, with a “Prince” piloting a “Claughton”.

You can read more on

“The Midland Scotsman”,

“The Royal Scot”

and

“The Story of the LMS”

on this website.

No. 5999 “Vindictive”, one of the re-

No. 5999 “Vindictive”, one of the re-