Ireland’s Railway Systems

From Small Beginnings to Great Achievements

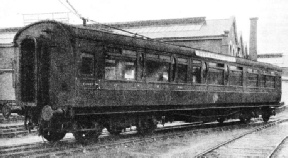

THE “NORTH ATLANTIC EXPRESS” of the Northern Counties Committee (LMS) system leaving Belfast. This express maintains a daily service between Belfast and Portrush -

FROM the beginning of the railways until to-

There are four principal railways -

The railways which were entirely within the Irish Free State were combined on January 1, 1925, into the Great Southern Railways, which, at the time of writing, operate 2,157 miles of 5 ft 3-

The standard gauge of 4 ft 8½-

The first railway in Ireland was the Dublin and Kingstown Railway, which was opened to the public on December 17, 1834. It connected the capital with the port of Kingstown, now called Dun Laoghaire, and was about six miles in length.

The project had to overcome considerable opposition. One opponent, Mr. O’Hanlon, told a Railway Committee of the House of Commons in 1833 that it “would be a monstrous thing that the solid advantages of commerce, manufactures, and all the blessings resulting therefrom, should he sacrificed to a few nursery maids descending from the town of Kingstown to the sea at Dunleary, to perform the pleasures of ablution.”

Kingstown, originally called Dunleary, was at one time a fishing village. But the mouth of the River Liffey became choked with sandbanks that made the approach to Dublin very difficult for vessels of any size. Therefore a harbour was built by the engineer Rennie, who began work in 1816, and the place was named Kingstown when George IV visited Ireland in 1821.

The contractor who undertook the construction of the railway became a national character. He was William Dargan, and he was described as a “prompt, sagacious and far-

The Dublin and Kingstown Railway was intended to be opened in June, 1834, but there was a delay owing to many difficulties. A few days after the permanent way had been completed a storm of exceptional violence demolished the bridge across the Dodder at Lansdowne Road.

In September “The Dublin Penny Magazine” announced: “The Railway will be opened on the 18th of the present month. His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant, several noblemen, members of Parliament, and a number of gentlemen have notified their intention of being present on the occasion. We have heard that there will be on the road fifty carriages, and six locomotive engines such as that shown in the engraving, which will convey one thousand persons who have been particularly invited for the occasion.”

A Successful Trial

There appears to have been a hitch, as the first trials were not made until October 4, when the steam engine “Vauxhall”, with a small train of carriages “filled with ladies and gentlemen” travelled from Dublin to the Martello Tower, Williamstown, a distance of two and a half miles. The trip was made four times in either direction, at a speed of thirty-

On the next day the “Hibernia” drew the train to Salthill in sixteen minutes, “notwithstanding the many difficulties attendant on a first starting.”

A journalist, anticipating the success of the railway, penned the following purple passage: “Hurried by the invisible but stupendous energy of steam the astonished passenger will now glide like Asmodeus over the summits of houses -

The gauge was the English standard of 4 ft 8½-

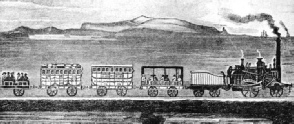

IRELAND’S FIRST RAILWAY. The above picture shows the first train on the Dublin and Kingstown Railway passing Merrion on its journey to Kingstown. The four classes of carriage are all shown. The line was opened in 1834 and the gauge was the English standard -

IRELAND’S FIRST RAILWAY. The above picture shows the first train on the Dublin and Kingstown Railway passing Merrion on its journey to Kingstown. The four classes of carriage are all shown. The line was opened in 1834 and the gauge was the English standard -

The line was opened on December 17, 1834, and the “Dublin Evening Post” published the following account:

“This splendid work was yesterday opened to the public for the regular transmission of passengers to and from Kingstown and the immediate stage of the Black Rock.”

“Notwithstanding the early hour at which the first train started -

“Up to a quarter-

"The utmost precautions were, how ever, taken to prevent the possibility of accident by stationing men at proper intervals along the road, and the trains at starting were propelled slowly for a short distance for the same object. Although there could not have been less than from three to four thousand persons upon the railway during the day, we are happy to state that these very necessary precautions were attended with the desired effect."

“The carriages started every hour during the day from either point of the line,” stated “Saunders’ News-

Four Classes

The carriages were of four classes: first, second, closed second, and third. A contemporary account stated: “The railway coaches of the first and second class may be almost called elegant; the third-

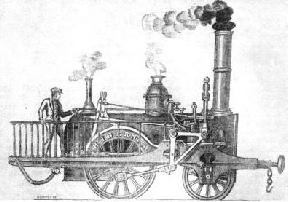

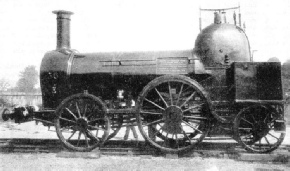

ONE OF THE FIRST LOCOMOTIVES IN IRELAND was the “Hibernia”. The engine was designed by Richard Roberts of Manchester. It possessed single driving wheels of 5 ft diameter. The leading wheels were 3 ft in diameter. Its horizontal boiler operated at a pressure of 75 lb, and the cylinders, mounted vertically, had a diameter of 11-

ONE OF THE FIRST LOCOMOTIVES IN IRELAND was the “Hibernia”. The engine was designed by Richard Roberts of Manchester. It possessed single driving wheels of 5 ft diameter. The leading wheels were 3 ft in diameter. Its horizontal boiler operated at a pressure of 75 lb, and the cylinders, mounted vertically, had a diameter of 11-

The locomotive “Hibernia” was designed by Richard Roberts, of Sharp, Roberts and Company, who established works in Manchester in 1833 for the manufacture of locomotives. It had a single pair of driving wheels, 5 ft in diameter, and a pair of leading wheels 3 ft in diameter. Although a horizontal boiler working at a pressure of 75 lb was adopted, the cylinders were mounted vertically over the centre line of the leading axle. They were 11-

Three locomotives of this type were built; but they proved a failure, the bell-

When the extension of one and three-

Although the original line from Dublin to Kingstown was only six miles long, it cost over £300,000, and was therefore among the most expensive of the early railways. Despite this, the Dublin and Kingstown Railway, which has long since been incorporated in the Great Southern system, was a paying concern, dividends as high as ten per cent being paid for the year ended March 31, 1846.

In comparison with England railway construction in Ireland was slow. The next line to be opened was in 1839, when the Ulster Railway Company opened a railway from Belfast to Lisburn, about seven miles, and extended it in 1841 to Porta-

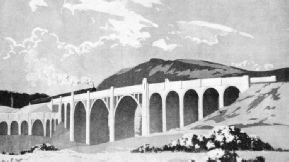

THE BOYNE VIADUCT, DROGHEDA. This viaduct carries the Great Northern Railway Company’s main line, between Dublin and Belfast, over the River Boyne, some thirty-

The time for the thirty-

By 1845 the three railways of Ireland covered a total of only seventy miles, compared with about 1,700 miles in Great Britain. In 1847 one of the worst disasters in the economic history of Ireland, the Great Famine, occurred. The earnings of the railway companies fell considerably. English capitalists were chary of investing in Irish railways, and work on new lines was held up by the lack of money. After the Great Famine, however, the work of building railways proceeded, and every year saw further lengths of line opened to traffic.

The first three railways had lines of three different gauges, the dimensions being: Dublin and Kingstown Railway, 4 ft 8½-

A Royal Commission was set up to report on the muddle, with the result that the width of the Irish gauge was fixed at 5 ft 3-

The construction of the early railways was a task of considerable magnitude. For example, on the Londonderry and Coleraine line it was decided, in 1846, to blow a hill, through which a tunnel had been been begun, into the sea. A heading or gallery was hewn in the rock from the side of the cliff, 50 ft in length, at the end of which a shaft was sunk for 22 ft to the level of the railway. Another gallery was made at the bottom, running at right angles to the first one, and farther into the rock. At the end of this was placed a charge of 2,400 pounds of black-

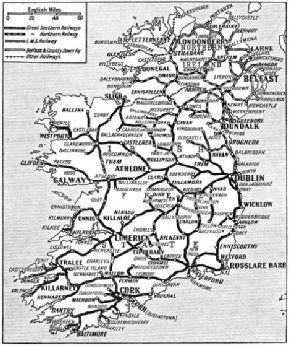

THE RAMIFICATIONS OF IRELAND’S main railway systems, whose total mileage is about 3,000, are shown on this map. In addition there are also a number of local railways.

THE RAMIFICATIONS OF IRELAND’S main railway systems, whose total mileage is about 3,000, are shown on this map. In addition there are also a number of local railways.

The famous engineer, I. K. Brunel, whose name is more particularly associated with the Great Western Railway, did not confine his attention to England. Possibly his most spectacular work was carried out on a stretch of line between Bray and Wicklow, some sixteen miles in length. It was said the Bray Head could not be conquered, and Brunel accepted the challenge. At one point south of Bray he bridged a wild ravine with a wooden viaduct 300 ft long and 75 ft high. Before it was quite finished it was destroyed in a night by the sea, and another was built. A few years later a train was derailed while crossing. It was found that the waves had battered the piers of the viaduct with such force that the vibration of the whole structure had thrown the rails out of gauge, and the viaduct was abandoned. In places the line was on a ledge 70 ft above the sea, enclosed here and there by a roof to protect the track from stones falling from the heights above it. The line was very costly to maintain, £40,000 being spent in ten years on defence works, and the shareholders did not appreciate Brunel's spectacular achievement, which was so costly to maintain against the elements.

In the early days the Irish railways were somewhat haphazard. There is a story that on one line some locomotives were altered from tender engines to tank engines, and that the brakes of this type, which were on the tenders, had disappeared in the process of alteration. When the driver wished to stop a train, having no brakes on his engine, he whistled. The guard heard the whistle and then applied the brakes.

An accident with a terrible death-

It is said that some passengers were in the guard’s van of this section, and that, in an attempt to help the guard by applying the hand brake, they turned the handle the wrong way, releasing the brake instead of applying it. The carriages gathered speed and went faster and faster down the incline, until they crashed into the other train, with terrible results. Except for the Quintinshill accident, in 1915, which involved an estimated death-

But in spite of this terrible accident, the Irish railways have always been noted for their efficient operation.

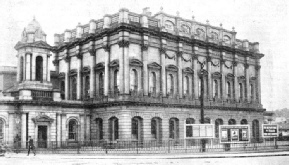

KINGSBRIDGE STATION, the main Dublin terminus of the Great Southern Railways. In 1925 all the lines wholly within the Irish Free State were amalgamated into one enterprise, “The Great Southern Railways”. The company operates 2,157 miles of 5 ft 3-

During the various “troubles” the railways suffered considerably from all parties. In the Easter Rising of 1916, stations in Dublin were taken over by the Irish Volunteers, but were evacuated. Then the military authorities restricted passenger traffic and used some of the stations as barracks. The permanent way was blown up in several places and a cattle train was derailed. On one occasion an engine was set running uncontrolled over a section of the line, but was thrown off before any damage was done. The curfew law in Dublin, Cork, and Belfast limited suburban evening traffic, and from time to time there were strikes and boycotts. Certain areas were closed by the authorities and markets were stopped, so that the railways lost passenger and goods traffic, and, in addition, certain lines were closed altogether.

During the Civil War in 1922 rails were torn up, bridges destroyed, and trains derailed or fired upon. A Railway Protection, Repair, and Maintenance Corps was formed, temporary repairs were made. blockhouses were set up along the lines, and armoured trains were run. Indeed, few railways have had so many difficulties with which to contend as those of Ireland.

The Largest System

The Great Southern is the largest railway in Ireland, its route mileage -

The line running south from Dublin passes the frequented seaside resort of Bray (Bri Chualann), which is also a centre from which to explore the beauties of County Wicklow, “the Garden of Ireland”. Farther on beyond Greystones, is the picturesque town of Wicklow. The Devil’s Glen, a lovely mountain pass, is near. After Wicklow the line leaves the coast and runs via Rathdrum to Avoca, near the “Meeting of the Waters”, about which Thomas Moore, the Irish poet, wrote a song. Avoca and Woodenbridge, just beyond it, are in the heart of delightful country. The railway goes on through the old town of Arklow to Macmine Junction. Hence one line runs south-

Another route from Dublin to Waterford goes through Kildare, Portarlington, Maryborough, and Kilkenny, while between these two routes is a web of connecting lines. West from Waterford the network of lines covers the south-

THE IRISH GAUGE is 5 ft 3-

Cork city is the centre for the tourist who wishes to see this part of the country, and it is served by lines branching out in all directions. Cobh (Queenstown), the Atlantic port, is one of terminals of the Great Southern. A line runs east from Cork to Youghal, from which port Sir Walter Raleigh, its mayor, sailed to found Virginia. To the north a line runs parallel with this one, connecting Mallow and Waterford, and tapping beautiful country. Southwest from Cork a line, with a number of branches to the coast, runs to Bantry, through Bandon. From Mallow a line runs westward, branching south to Kenmare, and west to Killarney, to Tralee, and to Valencia. From Tralee a line goes through the Dingle peninsula. Another branch runs from Tralee through Listowel to Limerick city, the third town in the Free State. The power station of the Shannon Electricity Scheme is situated at Ardnacrusha, three miles away, from which radiates the network of high-

From Limerick a line runs to Ennis, the chief town in County Clare, which is a junction, one railway going west and then south along the coast, and the other going north to Athenry (for Galway), Claremorris, and Sligo. The cliff scenery all along the coast-

Galway, with its fine harbour, on the west coast, is reached from Dublin by the main line that crosses the Central Plain of Ireland. The town’s records go back to 1124, and many Anglo-

The Aran Islands, reached by steamer from Galway, are attractive, the islanders being people with a character of their own, and might be a race apart from those on the mainland.

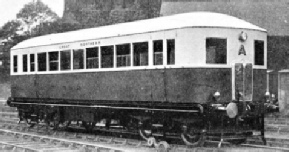

AN INNOVATION on the Great Northern Railway of Ireland is the pneumatic-

AN INNOVATION on the Great Northern Railway of Ireland is the pneumatic-

The line runs west into Connemara from Galway, the train journey being a revelation of successive scenes of beauty -

The northward continuation of the line from Ennis connects at Athenry with the main line from Dublin to Galway. Beyond Athenry is Claremorris, a junction for a line to Manulla Junction, whence one branch runs West to Westport, Mallaranny, and Achill, and the other north to Ballina. Mallaranny is the headquarters for tourists exploring West Mayo. It is screened from the Atlantic gales by the mountains of the Curraun Promontory. Facing Achill is the largest island on the Irish coast, Achill Island, which has an area of about fifty-

Sligo, an important seaport, is connected with the western network of railways via Collooney, near the end of the long branch from Limerick, Ennis, and Claremorris.

Central Ireland is served by the sections and branches of the Great Southern system, which extends from Cavan in the north to mid-

Ballybrophy is the junction for the Birr (Parsonstown) and Roscrea and Nenagh branches. The Roscrea-

Athlone, near which is a, powerful radio transmitting station, is almost in the centre of Ireland. It lies on both banks of the Shannon. The railway station is on the west side of the river, the longest in Ireland, which is spanned by a fine railway bridge.

MODERN RAIL DEVELOPMENT IN IRELAND. A Diesel rail-

MODERN RAIL DEVELOPMENT IN IRELAND. A Diesel rail-

The chief features of the district served by the Meath branch of the western main system are the Boyne Valley and Tara, Trim, Bective, and their surroundings. The Boyne valley is at its loveliest near Navan. Near Kilmessan Junction, whence a branch line runs to Trim and Athboy, is the famous Tara Hill. Trim, the county town of Meath, is thirty miles from Dublin. About two miles south of the town is the parish of Laracor, associated with Dean Swift. “Stella”, chaperoned by Mrs. Dingley, lodged at Trim.

Among the early locomotives of the Great Southern is one, No.36 in the records of the company, of the “Bury haystack dome” type. It was built by Bury, Curtis, and Kennedy, of Liverpool, in 1848, and incorporated the distinctive design favoured by these builders. It is of the 2-

THE “KESTREL”, a three-

The firebox is of copper, fitted with bar crown stays, and screwed iron stays in the water spaces. In addition to the doming of the firebox wrapper-

The heating surface of the tubes is 1,000 sq ft, and of the firebox 60 sq ft, giving an aggregate heating surface of 1,060 sq ft; the grate area is 12·75 sq ft. The working pressure is 80 lb per sq in; and the tractive effort, at 85 per cent of the boiler pressure, is 4,250 lb. The overall length of the engine is 21 ft 2-

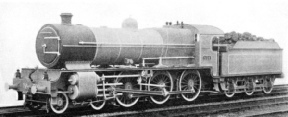

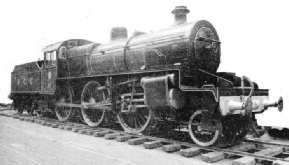

A HEAVY PASSENGER LOCOMOTIVE. 4-

This locomotive covered 487,919 miles in a quarter of a century of service, being withdrawn from service in January, 1874. The company, then the Great Southern and Western Railway of Ireland, set her upon a pedestal at their locomotive works at Inchicore for permanent preservation as an example of good workmanship.

One of the most interesting inventions of recent years is the Drumm Traction Battery, invented by Dr. J. J. Drumm. This battery is used for road and rail transport, and has operated eighty-

A 4-

Large-

The original Drumm train was constructed in the Great Southern Railways workshops at Inchicore.

Trial runs in January, 1932, showed that the train could attain a speed of fifty miles an hour within fifty seconds of the start. A speed of fifty-

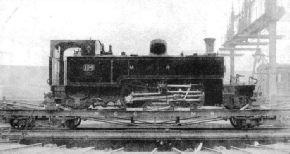

ON THE NARROW GAUGE. A goods train climbing a bank of 1 in 40 on the Northern Counties Committee line. The train is hauled by a 2-

The area served by the Great Northern Railway has its full share of historic associations and picturesque scenery. The company links up the Free State with Northern Ireland and was incorporated by an Act of 1877 which amal-

Since incorporation the Great Northern has acquired ten other railways, and built four branch lines. The company is a joint owner, with the LMS Railway, of the County Donegal Railways. Connections are made at Dundalk and Newry with the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway (twenty-

Coast and country are served by the ramifications of the Great Northern. The track runs by the Irish Sea, inland along trout-

Drogheda is an ancient town which has suffered from warfare, burnings, and pillage. It has reminders of its ancient history in the parts of the old walls that still surround it, while the St. Lawrence Gate and the Magdalene Tower are almost perfect.

Armagh, another ancient city which also suffered from warfare, burnings and pillage, is the primatial see in Ireland for the Roman Catholic and Episcopalian Churches. In the olden days it was a centre of education for students from all parts of Europe.

A Frontier Line

The Great Northern Railway forms roughly a gigantic Y, with three of Ireland’s chief ports at its three ends: Dublin (with Kingstown), Belfast, and Londonderry. The company claims to have been the first in Great Britain and Ireland, if not in the world, to have its entire passenger rolling-

In the comparatively small area that it serves. the railway crosses the frontiers and customs barriers of Northern Ireland and the Free State at nine places.

The Great Northern terminus at Dublin is at Amiens Street Station, which covers three and a half acres, and has three platforms. Great Victoria Street Station, Belfast, covers four acres, and has five platforms. At each of the two stations about 2,500,000 passengers are dealt with yearly.

Passengers and mails by the night “Irish Mail” from London (Euston) and other centres in England via Holyhead, connect at Kingstown Pier with a train to Amiens Street (Dublin), where they are transferred to the morning mail train for Belfast. This train gives a connection at Dundalk for all stations to Omagh, taking in Carrickmacross, Cootehill, Cavan, and Belturbet branches; at Goraghwood with trains for Newry, Warrenpoint, Armagh, and Banbridge; and at Portadown for Londonderry, via Strabane. Including this train there are five restaurant or buffet car expresses daily in either direction between Dublin and Belfast (112½ miles).

THE NEW GREENISLAND VIADUCTS. The Main Line Viaduct in County Antrim is the largest reinforced concrete railway viaduct in the British Isles It is 630 ft long. and has a maximum height of 70 ft. The main arches in the Main Line Viaduct and the Down Shore Line Viaduct (the lower structure) have a span of 89 ft. Over 17,000 cubic yards of concrete, reinforced by 700 tons of steel, were required for the two viaducts. The higher one forms part of the loop recently built to cut out the reversal of trains at Greenisland.

An express leaves Dublin daily in the late afternoon for Belfast, giving connections at Drogheda for Oldcastle; at Dundalk for Carrickmacross, Cootehill and all stations to Enniskillen and Cavan; at Goraghwood for Newry, Warrenpoint and Banbridge. This train conveys passengers for Scotland via the Belfast and Ardrossan route. Passengers leaving Euston Station (London) by the day “Irish Mail”, and travelling via Holyhead and Kingstown, connect with this train, which enables them to reach Belfast in the evening of the same day.

Travellers by this route to Northern Ireland, and by the afternoon up Limited Mail from Belfast for cross-

There is a restaurant car express service between Belfast and Londonderry. The morning mail train from Belfast reaches Londonderry in just over two and a half hours. This train runs in conjunction with the Liverpool, Heysham, and Glasgow cross-

At Dublin there is a heavy seaside traffic with Howth, Malahide, and Skerries, and a frequent service that is increased to a fifteen minutes service on some occasions to carry holiday and residential traffic.

At Belfast the district up to and including Lisburn (eight miles) is residential. The service is half-

A considerable excursion traffic is carried from all stations during the summer to Bundoran, Warrenpoint, Newcastle, and other places at specially low fares. The excursion fare from Belfast to Warrenpoint and back is only two shillings for a total distance of 102 miles. The time occupied for the journey in either direction -

On such occasions as the July Orange Demonstrations, which are held at different places throughout Northern Ireland each year, the railway is called upon to carry some 30,000 additional passengers in a few hours, and this taxes the supply of rolling-

International football matches at Dublin and Belfast attract considerable extra traffic, and express corridor trains are run at cheap fares. The “Throughout Dining Car Express” is a popular train for Rugby enthusiasts, first-

Rail Omnibus Service

The system has connection at Amiens Street, Dublin, with all sections of the Great Southern Railways for passenger traffic to and from south-

At Cookstown and Antrim the services link up with the Northern Counties Committee (LMS); at Strabane with the narrow gauge lines (3 ft) of the County Donegal Joint Committee, and at Londonderry with the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway (3 ft gauge) At Newcastle, and Belfast via the Belfast Central Railway, connections are made with the Belfast and County Down Railway. The Belfast Central line also affords through conveyance of a considerable goods and live stock traffic to and from the Belfast quays with the cross-

Connections are also made at Dundalk and Newry with the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway, for the cargo steamships operating between Greenore and Holyhead.

Traffic between Northern Ireland and the Free State is subject to customs examination at the boundary posts. The customs authorities and the railway company have, however, arranged for the examination to take place in the trains. There are boundary posts in Northern Ireland at Goraghwood, Tynan, Newtownbutler, Belleek, and Strabane; and for the Irish Free State at Dundalk, Clones, Monaghan, Pettigo, Ballyshannon and St. Johnston.

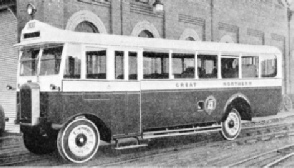

An innovation on the Great Northern is the pneumatic-

THE MOST POWERFUL LOCOMOTIVES on the Northern Counties Committee system are the new 2-

It resembles the ordinary omnibus. The wheels have steel rims interposed between the pneumatic tyre and the rail. The rail omnibus has the advantage over the steam train of being able to stop at level crossings, in addition to stations, to pick up or set down passengers. Besides being more economical to operate in sparsely populated districts, the rail omnibus provides a high degree of comfort.

The main line between Dublin and Belfast is carried over the River Boyne at Drogheda, about thirty-

A 5 FT 3-

The Northern Counties Committee (London Midland and Scottish Railway) is popularly known as the Northern Counties Railway. It has direct connections with the parent company in Great Britain by a service of LMS steamers between Stranraer and Larne, and between Heysham and Belfast. The railway serves the counties of Antrim, Londonderry and Tyrone.

The main line runs between the two largest centres of population in Northern Ireland, Belfast (the headquarters and principal terminus) and Londonderry. There are branch lines to Larne Harbour, Ballyclare, Cookstown, Draperstown, Portrush, and Dungiven. Narrow gauge (3 ft) lines between Larne Harbour and Ballymena, with a branch to Ballyclare, between Ballymena and Parkmore, between Ballymoney and Ballycastle, and between Londonderry and Strabane complete the system. Some branches are closed to passenger traffic.

The district served has many scenic attractions. These include the famous Giant’s Causeway; Lough Neagh, the largest lake in the British Isles; the celebrated Antrim Coast Road; the Glens of Antrim; and the Gobbins Cliff Path, said to be the finest marine walk in Europe. The chief industries are associated with the manufacture of linen, and include flax-

A RESTAURANT CAR owned by the Great Northern Railway. This company claims to have been the first in Great Britain and Ireland to have all its passenger rolling-

As with many other railways, the Northern Counties has been built up by the amalgamation of a number of small independent lines. The first section of the system, the Belfast and Ballymena Railway, was opened to Carrickfergus and Ballymena in 1848. The Ballymena, Ballymoney, Coleraine, and Portrush Railway was opened in 1855, and the Londonderry and Coleraine Railway was completed in 1853. Through rail communication between Belfast and Londonderry was, however, not established until the completion of the viaduct over the River Bann at Coleraine in 1860. In 1860 the Belfast and Ballymena Railway became the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway. Next year the Ballymena, Ballymoney, Coleraine and Portrush railway became amalgamated with it, followed in 1871 by the Londonderry and Coleraine Railway. A number of other railways were amalgamated in later years.

In 1903 the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway was taken over by the Midland Railway of England, and since then its affairs have been administered by the Northern Counties Committee. The Committee comprises members representing the English board and members representing Irish interests. While the line is operated as a distinct concern, and has its own officers and staff, it maintains close association with the directors and chief officers of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, as the successors of the Midland Railway Company.

Gradients are frequently severe on all sections of the system, but 1 in 80 is seldom exceeded on the broad-

There are only two tunnels on the system, both single line and quite short, one being at Downhill and the other at White-

Important engineering features are not lacking, outstanding examples being the loop line at Greenisland and the viaduct over the River Bann at Coleraine.

LEAVING DUBLIN. A Great Southern Railways train, hauled by a 4-

The Greenisland Loop, between Belfast and Antrim, built in 1931-

The plans were prepared and the entire work was undertaken by the railway, involving an expenditure of £250,000, towards which the Government of Northern Ireland contributed £80,000.

The loop line has a continuous gradient of 1 in 75. It required the excavation of about 240,000 cubic yards of earth and the placing of the earth in new embankments. The maximum cutting is 22 ft and the greatest height of the embankment is 35 ft. The greater part of the line is on a continuous curve, the maximum radius being three-

A short distance from the beginning of the new loop line at Whiteabbey there is a wide glen over which the new line had to be carried at a considerable elevation. As the maximum depth was 70 ft a viaduct was necessary, and one of reinforced concrete was built in eighteen months. In addition to the three main arches of 89 ft, there are a number of approach arches on either side of 35 ft span.

Down trains for Larne pass underneath the new loop line at the Belfast end of the main viaduct, so that one line is above the other. This down line crosses the glen at a much lower elevation than the big viaduct, and it is carried by a concrete arch of 89 ft span, with three 35 ft approach arches on either side. The two viaducts and the under-

A DRUMM TRAIN passing through Lucan Station, Co. Dublin. This train is operated by the quick-

The new part of the line passes underneath a county road, which is carried on a three-

To provide a direct connection from the north to Larne Harbour for the Stranraer steamer, a single line has been retained from a point half-

Colour light signals were installed at Greenisland and Ballyclare Junction, the first station at the end of the new line. The signalling is controlled from a central cabin at Greenisland, and the points at the junction are operated by electric motors. There are electric train indicators in Belfast and Greenisland signal boxes, and there is also an illuminated diagram at Greenisland.

The construction of the loop line, together with minor adjustments made to the crossing loops on the railway north of Ballymena, has reduced the time taken between Belfast and Londonderry by more than twenty minutes and the time between Belfast and Portrush by twenty-

The “North Atlantic Express”

Portrush, in addition to being a seaside resort and golfing centre, is a residential centre for the business and professional people of Belfast.

The River Bann Viaduct, opened in 1924, replaced the original viaduct built in 1860. The new structure consists of eleven spans; five fixed spans on the Coleraine side, the counter-

The “North Atlantic Express”, instituted after the opening of the Greenisland loop, maintains a daily service between Belfast and Portrush (sixty five and a quarter miles), and is particularly convenient for Portrush residents whose business interests are in Belfast. This express leaves Portrush in the morning and arrives in Belfast after a run of eighty minutes, The corresponding train from Belfast leaves in the evening on week days, except on Saturdays, when it leaves soon after midday. There is a stop at Ballymena in either direction.

This train is usually hauled by a 4-

The rolling-

The body framing of the coaches is of teak, with mahogany panelling outside and inside. The exterior of the train has been designed to give an almost flush finish, and with the large 5-

Above the window in each compartment, and also in the corridors, a sliding extractor ventilator is fitted.

The most powerful Northern Counties locomotives are those designed recently for service in Ireland by Mr. W. A. Staneer, Chief Mechanical Engineer of the LMS Railway. These have the 2-

THE NORTHERN COUNTIES COMMITTEE has constructed rail-

You can read more on

“The Great Southern & Western Railway”

and

and

“The ‘Limited Mails’ of Ireland”

and

and

on this website.