NEW ELECTRIC TRAIN FOR SOUTH EASTERN SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY

RAILWAY electrification is enormously costly, and when it is complete, there must be a reasonable expectation that the saving in the cost of working the electrified railway will be big enough to pay “interest” on what has been spent in equipping it electrically. Besides that, the fact that there is no further use for all the steam engines on the line cannot be overlooked.

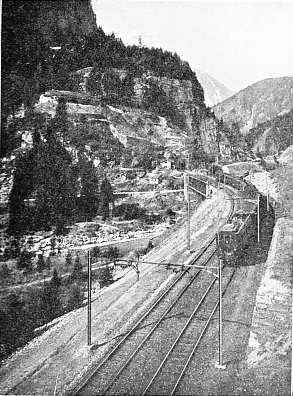

There are only certain conditions, so far as the science of electricity has yet proceeded, in which electrification of railways “pays”. In a mountainous country like Switzerland, which has enormous resources of water power, the rushing water in the valleys can be harnessed to drive dynamos, and electricity is thus produced at a very small cost. Thus the Swiss are now in course of electrifying all their railways, and the work is well on the way to completion.

Then, again, where the gradients are steep and the loads are heavy, so that two, or even three, engines have to be used together, electrification pays, because it is possible to cut down the number of engines and crews in service, and to speed up the trains. Mountainous country, heavy gradients and water power generally go hand-

“OVERHEAD” ELECTRIFICATION ON THE ST. GOTTHARD RAILWAY

Then, again, electrification pays in the case of very dense suburban passenger services, such as those all round London. Electric trains can get up speed very much quicker than steam trains, and electrification thus results not only in faster suburban trains, but in the possibility of putting many more trains on the line, so saving the expense of laying more tracks. On parts of the electrified “Inner Circle”, and on some of the tubes, there are to-

The earliest electric railway of any importance in the world was the City and South London tube, from the Bank down to Clapham Common, opened in 1890. On this line separate electric locomotives were used, and the example was at first copied by the “Twopenny Tube”, in 1900, but both have since changed over to the use of motor-

LONDON TUBE RAILWAY ELECTRIC MOTOR-

Separate electric locomotives are used, however, when trains without electrical equipment are required to run over the electrified lines, such as the Great Western trains which run round the “Circle” to Aldgate. Similarly, on electrified main lines, the independent electric engine is always employed, so that any type of passenger or goods rolling stock may be used in the making up of the trains. Electric engines, too, are coming into use for shunting purposes, as in the case of the L & NE engine at the end of the chapter, which works up a very steep incline from the Tyneside quay up to the high level at Newcastle.

ELECTRIC TRACK EQUIPMENT NEAR ACTON

You will notice in the photographs the two distinct methods that are used for supplying the electric current to the trains. One is the “overhead” system, and the other the system known as “third rail”. Of the two the overhead is generally the cheaper to instal, but in this country, owing to the tight “fit” of our coaches under bridges and tunnels, the use of overhead equipment has presented considerable difficulties.

“OVERHEAD” ELECTRIC TRAIN ON THE BRIGHTON SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY

The only British lines of any importance with overhead electrification are the London suburban lines of the Brighton section of the Southern Railway, the Midland, Lancaster and Heysham line of the LMS, and a London and North Eastern branch carrying a heavy mineral traffic from the mining area of south-

In the third-

THE RIVALS -

You can read more on

“Electric Power on the Grand Scale”,

“Electrification in Europe” and on

on this website.