The Conquest of Death Valley

How the railway was driven through the alkali desert of Nevada

THE TONOPAH AND TIDEWATER RAILWAY IN DEATH VALLEY. The engine hauls its water supplies. This photograph gives a striking idea of the sterile character of the country.

WHEN the steel ribbon was to be flung across Nevada’s sizzling waste of alkali between Ludlow and Rhyolite, the name for the enterprise seemed obvious, if prosaic. But suddenly someone referred to the undertaking as the “Tonopah and Tidewater Railway”. One of the engineers is credited with the expression, which must have been perpetrated in an outburst of cynical jest, seeing that the railway was to run neither to Tonopah nor to Tidewater. However, the two “T’s” proved irresistible, and forthwith the undertaking was given the alliterative title. Since then it has redeemed its application somewhat, as the northern end now does connect with Tonopah. but the southern extremity is as far from the coast us ever; access thereto is provided over the tracks of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe system, which runs through Ludlow on its western way to the Pacific seaboard.

Yet the engineer's inspiration was timely. Otherwise a lugubrious name, adapted to the surroundings, might, have been evolved, because this important road traverses a dismal country where sinister sobriquets and grim traditions abound. It offers an easy approach to the ill-

The few strange workers in this inhospitable corner of the world would have remedied the deficiency of title very promptly but for the engineer’s ingenuity; they have a grim humour which is fitted peculiarly to circumstances. It does not demand a very vivid imagination to conjure such baptisms as the “Skeleton and Death Valley Fast Line” or the “Funeral Trunk Road”. But, being forestalled by the engineer, and the alliterative title effectively combating all efforts to be superseded, the desert toilers have been forced to content themselves with nicknaming the trains, “The Skeleton Limited”, “The Death Valley Express”, “The Fast Funeral”, and so forth.

Yet the “T. & T.” railway itself is no joke. In fact, it ranks as one of the most important lines in the State. By linking up with the “Bullfrog Coldfield” and Tonopah railways it offers a short cut across the length of Nevada. From end to end it traverses blistering desert, where the stunted cactus only can secure a root-

MAP OF THE DEATH VALLEY RAILWAY.

Probably in no other corner of the North American continent is absolute sterility emphasised in such compelling form as the district served by the “T. & T.” railway throughout its length of 175 miles. For years Death Valley was shunned as if stricken with the plague, and the surrounding desert was aptly described, with its eternal temperature ranging from 100° upwards, both day and night, as “Hades with the lid off”. Its ill-

Notwithstanding this grim atmosphere, Death Valley ever has exercised an irresistible fascination to those who will not be baulked by any opposition of Nature in the eternal struggle for existence. The valley reeks with wealth incalculable. As a rule, it is the Golden Fleece which tempts the hardy and devil-

The bold and daring were not prepared to let this opportunity to amass wealth to pass without a determined effort to materialise some castle in the air. Small parties of gaunt, riotous, happy-

The success of these hardy, adventurous, and plucky prospectors tempted the capitalists. The “rats”, although they had found riches beyond compute, were without all means of transporting their wealth to the markets. So they were financed to consummate this end. The desert demanded peculiar methods. These were forthcoming. Huge boxed vehicles, slung on large wheels without springs and with tyres 7 inches in width to prevent sinking in the soft sand, were built at a cost of £200 or so apiece, and were hauled by teams of mules, which, in their labouring over the blinding, thirst-

But things move quickly even in the desert when commercial development gets into its stride. One hardened prospector returned to the cities with specimens of low grade nitre, which he said abounded in plenty; another brought finds of copper; a third stumbled upon traces of silver; while immediately north of the country gold was found in rich paying veins.

The inevitable happened: the railway must be run into the country. That and nothing else could bring the region within the compass of commercial expansion and development. So the “T. & T.” railway was born. A small band of surveyors set out from Las Vegas, the nearest station on the San Pedro and Salt Lake City Railroad, to drive their way westwards between the Charlston and Kingston mountain ranges into the sinister gulch. They brought back a feasible project, which was adopted without delay.

Construction was hurried forward. Large gangs of navvies, accustomed to driving the steel through the desert, were brought up with vast supplies of material and provisions. Las Vegas was to be their base, and they were to move forward like an invading army across the scorching wastes, with the completed track ever on the heels of all to bring up food and water, because the country traversed could not yield a drop of drinkable liquid nor an ounce of foodstuff.

Although a promising start was made with the grade, the enterprise was not proceeding smoothly. A dispute arose between the new concern and the railway with which it was linked, and the former was aggrieved. Quietly the “T. & T.” approached the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe system to see whether it could not be linked up with them. At the same time the surveyors were sent into the desert once more to plot a new route, in the event of the latest deliberations proving successful.

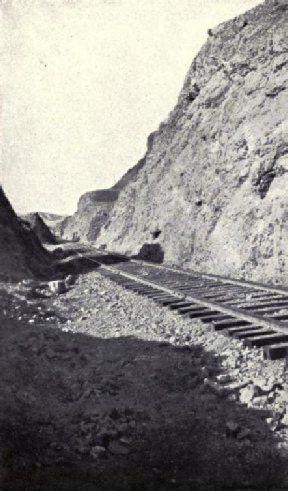

THE TRACK THROUGH THE BLISTERING BORAX AND NITRE GULCHES.

One evening in September, 1906, all the men working on the grade out from Las Vegas received a curt summons to “down tools”. At the same time they were ordered to load all immediate requirements into a waiting train, and the desert had long been wrapped in the mantle of night ere the hurried task was completed. Then the navvies were ordered to take their seats, and without any fuss whatever the train steamed away to the south-

When the morning broke Las Vegas was deserted. Not a navvy was to be seen on the grade; there was not a single tool lying about. What was the matter? Had the new line met early sudden death? Yet what seemed to be an inscrutable mystery was soon solved by the ticking of the telegraph wires. The train which had departed so hurriedly overnight, ostensibly for the west, had stopped at the little station of Ludlow, on the Atchison, Topeka and Saute Fe line. The tools and supplies had been pitched out, and the navvies were toiling for all they were worth upon a new grade. The San Pedro line had been thrown overboard: a rival had given what they had refused.

The engineers and their army of one thousand nondescript, hardened navvies set to work with great gusto: time had been lost on the initial unavailing start at Las Vegas. The standard gauge was adopted, since Tonopah was not the ultimate limit of northern railway travel.

Tradition, history, and superstition demanded elaborate precautions to preserve the humans slaving on the semi-

The railway grader is a curious individual. He will labour hard and long uncomplainingly, tolerate unmerciful climatic conditions without a murmur, and suffer isolation ungrudgingly so long as he is well fed. Moving a force of a thousand men over a pitiless desert is anxious work under the best conditions. While the navvies were busy wrestling with the heat and sand the controlling forces were absorbed in keeping the front well supplied with every little requirement. At night, when the graders had rolled themselves in their blankets and had laid down to a hard well-

The construction camps were flung out over the drab desert for a distance of 20 miles beyond the point where the last rail was laid. Supplies were sent up by train as far as possible and then shifted onwards by mule teams. Beyond the rail-

The awful loneliness, torrid heat, dust-

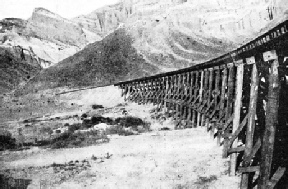

A HEAVY STRETCH OF TRESTLING. Every piece of timber had to be hauled several hundred miles.

Nevada has always enjoyed the reputation of being a quaint state where the laws are observed in a peculiar way, where the ideas of capital and labour have an unusual interpretation, and where Jack insists that he is better than his master. But on this undertaking there was never the slightest hitch or difficulty. The engineers took elaborate care that the inflammable prevaricator, alcohol, did not invade the camps. Tea, coffee, and cocoa are not very powerful stimulants to quarrelling, and so the camps, with their rough-

It was when the railway entered the Armagossa Canyon that the most difficult work was encountered. For part of the year this “sink” is a borax swamp; for the remainder it is an oven. The railway clings somewhat to the mountain side, and a gallery had to be blasted and hewn out, deep cuts driven through friable hills, and yawning depressions filled with the unstable spoil or spanned by lofty timber trestles. The slender line of communication was taxed heavily, inasmuch as every ounce of material had to be brought in; the country did not yield anything of value to the builders beyond earth for the grade. If a cord of wood were required for the camp fire, then the telephone clanged frantically, and the fuel was hurried up with as much speed as a consignment of spikes to clinch the rails to the sleepers.

It was a dreary northward pull. The mountain sides, catching the fierce heat of the sun, acted like firebricks and reflected a sultry glow when the sun had dipped behind the Sierras, so that night brought practically no relief. In the heart of this arid blotch upon the American landscape rises the Armagossa River, a stream of saturated soda and borax which, after running for a few miles, comes to a stop in a basin to dry up under the fierce heat of the summer sun or to be absorbed by the surrounding waste of borax, soda, nitre, and what not. As the graders pushed farther and farther into the dismal zone they became more and more sullen. The desert navvy is not a very loquacious individual at the best of times: but when his senses became dulled by the everlasting glow of glistening white he became taciturn almost to dumbness. To him there appeared to be only one object in life -

As the graders drew near the haunted depression they secured a little relaxation: were confronted with fresh faces. The “desert rats” came out of their holes and burrows to watch the advance of the steel highway. As companions they were not a success. Locked up in the mountains, they had only tatters of news to discuss round the camp fires. They emerged rather for the purpose of hearing something from the graders. When all available items of news were worn threadbare the trend of conversation took a new turn, and some of the stories related round the camp fire when the day’s work was done would make a town-

About 100 miles north of Ludlow a spur radiates from the main track into the heart of the Funeral Range, with road communication into Death Valley itself. Death Valley station is an important junction, and the “rats” will tell you that it is going to be “the ro’r’nes’ place on earth”. Three stations beyond is Gold Centre, whence the “T. & T.” swings off westwards to Rhyolite. The traveller, determined to get to Tonopah, continues over the Bullfrog railroad to Goldfield, and thence to Tonopah on the northernmost rim of the desert. Thence the journey may he resumed by rail northwards through Carson City, finally gaining the Union Pacific Railway. Prior to the construction of the “T. & T.” the great systems of the country described a big loop around the State of Nevada, as if fearing to venture too far into its arid wastes, so that to pass from Los Angeles to Carson City involved a long detour, either via San Francisco or by way of Salt Lake City. Now one is able to cut across the length of the State speedily and in comfort.

When at last the railway was completed and the day of its official opening arrived, the event was celebrated in true Nevada fashion. All the great of the mining centres along the line let themselves go in the manner of the untamed West. The “rats” came down from the hills, and the miners came up from the depths with super-

Already the “T. & T.” railway is making its presence felt. The communities scattered along the route, which formerly were designated mining camps, now scorn such an appellation. Every one is a “city” -

The future of the “T. & T.” railway undoubtedly is governed by the development of the minerals abounding in the Death Valley country. But no apprehensions need be entertained on this score. Prospecting is being carried out upon an elaborate and scientific scale, possibly to reveal minerals which so far have not been identified with the country. Still, the output of soda, borax, nitre, silver, copper, and gold will suffice to return adequate dividends upon the money sunk in the effort to conquer this forbidding, scorched and ill-

You can read more on

“The Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway”

and

and

on this website.