Defying Death Valley

The Stupendous Drama of the Men who Drove a Railway Across Fiery Desert Sands

BEFORE THE RAILWAY CAME, a simpler mode of transport served the prospector in the desert.

THE Death Valley in Nevada and the burning alkali waste surrounding it might well be termed an inferno on earth. Even the approach of night brings no relief to the weary stretches of sterile land, cracked and parched in a temperature which never falls below a hundred degrees Fahrenheit.

To construct and run a railway, over two hundred miles long, across a territory shunned by all living things except rattle-

In this instance the eternal quest for gold did not primarily draw attention to Death Valley and the neighbouring country, a land quite as grim in character as the names designating such places as Skeleton Peak and Funeral Range. It was the discovery that the floor of Death Valley -

Civilization demanded borax and civilization was willing to pay for borax.

It constitutes one of the most important commodities in modern industry, for which it is in constant demand. Enamelling, glass, pottery, domestic requirements, chemical manufacture, tanning, soap, and metallurgy all need borax.

The penetration of Death Valley was seriously considered. Visions of fortunes to be had for their mere carting away tempted venturesome prospectors.

Adventurers, tattered wanderers and professional prospectors -

The fact, however, that the Death Valley furnace had been braved and partly overcome encouraged wealthy townsmen. They organized and financed a method of transporting the valuable mineral to the markets, for although great riches were certainly locked up in Death Valley, the first prospectors had as yet found no means of removing their borax from the spot and converting it into cash. A desert caravan of huge, box-

The journeyings of the Death Valley caravan were unimaginably arduous and primitive, and when the real significance of the further discoveries of nitre, copper, silver and gold became clear to the financial supporters of the mule transport comp-

The line, planned to connect Ludlow and Rhyolite, was inadvertently named the “Tonopah and Tidewater Railway”, though it did not reach to either of these places. (Such mis-

Known as the “T. & T.” line, it first showed signs of life with the departure of a small party of surveyors from Las Vegas, the station on the San Pedro and Salt Lake City Railroad nearest to the Death Valley region. Westward they trekked between the Charleston and Kingston ranges in the direction of the ill-

AN OLD MINING CAMP in Death Valley. The rich yield of mineral deposits was conveyed over light railways, such as those shown picture, to the main line through the desert.

As soon as the surveyors’ report on the locality and the suggested site of construction had been carefully examined and finally approved, the initial stages of the undertaking began. Building material, vast stores of provisions, and a veritable army of workers, the majority of whom were specially selected for their hardiness and experience in labouring under semi-

For a while, in the face of almost insuperable difficulties, the laying of the track from Las Vegas steadily continued. As new stretches of rail were spiked down, light engines conveyed more material and fresh supplies of food and water from the base to the constantly advancing railhead.

Then, without warning, the constructors were ordered, in 1906, to cease operations. Men, implements, baggage, and, in fact, the entire outfit, were indiscriminately loaded into a long freight train that toiled westwards during the night to the station of Ludlow on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe system. The following day the previous beehive scene of activity at Las Vegas had changed to one of forsaken stillness.

The solution of the mystery, and the reason for this unusual procedure, was not, as might have been imagined, the financial crash of the company concerned, but a sharp quarrel between the new line and the San Pedro and Salt Lake City Railroad. After failures to settle the dispute the “T. & T.” Railway had asked assistance from the mighty Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe line. This had been granted, and surveyors plotted a fresh route, with Ludlow as the new terminus of the daring project. This, then, was the cause of the abrupt and clandestine transference of men and material to the more westerly site.

Precious time had, of course, been lost during the weeks of the first and fruitless effort, and, to recapture this, the engineers drove their heterogeneous battalions with even greater zeal. No detail was overlooked in keeping the daily progress of the work up to schedule, while the organization of the food transport to the ever-

It does not require much imagination to picture the officials and engineers at the Ludlow headquarters busily and unceasingly struggling with the multitudinous problems that arose daily in connexion with their enterprise -

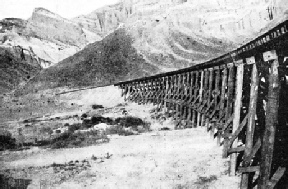

TRESTLE BRIDGES are a common feature of this remarkable desert railway. All material for their construction had to be hauled several hundred miles.

The site of the track-

Sometimes the supply train did not return empty to Ludlow, for there were many whom the desert’s fierceness over-

In the heroic story of this railway conquest of Death Valley one of the most salient chapters is the driving of the grade through the Amagossa Canyon, which, for half the year, is an impenetrable borax swamp, and for the other half is remarkably like a brick-

THE WATER PROBLEM. This picture illustrates in a very striking manner one of the chief problems confronting railway engineers in the desert -

Still, despite all obstacles, those of company politics and finance included, the railhead gradually advanced through the desert of borax, nitre and soda, almost red with the heat during the day and glowing in a sinister fashion long after sundown. The rails passed the Sierras, through the Amagossa Canyon, skirted the Amagossa river -

Through this dreadful canyon the progress of the building operations was retarded to a very large extent by the numerous cuts and fills necessary to ensure a safe bed for the rails. In the Amagossa Canyon, too, the builders constructed the largest trestle in the undertaking; it measured 540 ft. In all some two miles of bridges and pile trestles were erected during the whole enterprise.

The flood waters of the neighbouring Mojave River also increased the general difficulties of the construction, hampering and ravaging the work in hand, and at times weeks were required to restore the damage before further progress could be made. The maximum gradient on the line was made to be 1.5 in 100.

For the labourers on the track, induced into what was almost a natural oven by an unusually high standard of pay there was nothing left to do but to battle steadily forward, and they grew increasingly taciturn as the dead region impressed something of its awful solitude upon their minds. When, however, the line approached Death Valley itself, the workers enjoyed a slight diversion. The pioneer borax prospectors left their holes and caverns to greet the new-

Then, at last, astounding pertinacity and resource reaped their reward, and the railway was completed, about 170 miles of track having been driven across one of the most forbidding wastes in the world. The official opening of the line was duly celebrated, all the railway builders, miners and prospectors from surrounding districts assisting in violent and pyrotechnic style with salvos of six-

Thus was heralded the first real train on the “T. & T.” Railway, and it was not long before drinks -

The orgy of jubilation ran its natural course, but the memorial to the great victory over Death Valley -

Opening Up the Desert

To-

Through the triumph of the desert railway approximately 20,000 miles may be said to have been opened up for exploit-

The Tonopah and Tidewater Railway Co, Ltd, has now begun to make a part of this isolated region a winter resort. A hotel has been built near Death Valley Junction, at sea level, and sheltered by the barrier of the Funeral Mountains. Here an open-

MODERN METHODS. An up-

MODERN METHODS. An up-

Retrospectively, the most wonderful feature in the construction of the “T. & T.” was the Herculean task performed by each worker. In an era that tends as far as possible to eliminate the human factor from its projects and institutions, this brief epic provides a striking illustration of the truth that in reality the world progresses, not through ingenious machinery, but in the first place through the courage of individual men. There can be no doubt that defying Death Valley was indeed a notable episode in the annals of railway engineering, and one that, for sheer heroism, is fit to rank with the Sagas of the ages.

You can read more on

“The Conquest of Death Valley”

and

and

on this website.

You can read about

in Wonders of World Engineering