America’s First Trains

Their Origins and Early Developments

THE “ATLANTIC” locomotive, which was built at York, Pennsylvania, in 1832, by Phineas Davis. Ox teams were used to convey the engine to Baltimore. It made a successful first trip between Baltimore and Ellicott’s Mills (Maryland), a distance of thirteen miles. The “Atlantic” was in service for sixty years, and is still capable of running under its own steam.

TO understand the early trend of railway development in America we must first glance at the origins of American transport in general. The pioneers who built the first railways in the States were confronted by difficulties -

At the dawn of the nineteenth century the population of what then constituted the United States was still largely concentrated in territory lying along the Atlantic seaboard. To the west rose the Allegheny Mountains, forming the frontier; while farther west again was a vast region stretching far away to the Pacific -

The new territory was dominated by the Ohio, the Missouri, and the Mississippi rivers, with their tributaries. Farther north, men were spreading along the chain of great lakes. Naturally the early settlers in the west utilized these great inland waterways so bountifully provided by nature.

Danger of Indians

There was evolved by the pioneers a peculiar type of vessel suited to river requirements; a vessel of light draught known as a “flat-

Roads in the west there were none, until about 1796 Ebenezer Zane hacked his way through the forests of south-

American ingenuity and skill came to the rescue with a partial solution. In 1783 an inventor, John Fitch, succeeded in moving a boat on the Delaware River by paddles operated by a steam engine. Further developments were carried out by Robert Fulton, who built his first steam-

Despite dangers and difficulties, these steam-

Combined Railway and Canal

In those days canals were, of course, constructed without the mechanical aids that are available now. The network of artificial waterways that presently came into being was the product of human muscle applied to pick and spade. By 1832 there were eight hundred miles of canal in Ohio, and for thirty years the industrial development of that State continued to be largely determined by canal transport. Ultimately, several thousand miles of canal were constructed in the United States, many being carried over wide rivers on timber aqueducts and dug for long distances through dense forests. Rivers were so interlinked in this way that it became possible to travel by inland waterways from New York to New Orleans -

One hundred years ago few Americans could have realized that canals were destined to be superseded by railways. Yet even as early as 1812 there was one American, John Stevens, who realized that the future development of his country depended not upon water transport, but upon steam railways.

CROSSING THE ALLEGHENY MOUNTAINS in 1835 on the journey between Philadelphia and Pittsburg. The illustration shows a sectional canal boat being hauled over one of the inclined planes of the Portage Railroad. Traction was by means of a stationary engine and endless cable. The Portage Railroad was 36½ miles long, with a total rise and fall of 2,670 ft. The inclination of the planes varied from 7¼ ft to 10¼ ft in 100 ft.

Stevens had already carried out unsuccessful experiments with steamboats at New York; but failure in this regard, together with the loss of some 20,000 dollars, did not damp his enthusiasm for railways. In 1812 an act to authorize the construction of a canal from the Hudson to Lake Erie was pending; a canal, that is, which would form an effective link between eastern cities and the north-

But long before the completion of this canal the views held by Stevens had gained influential adherents. When another canal, from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, was projected, the opposition of these men was so far effective that a combination of railway and canal -

THIS HORSE CAR, built in 1829 and drawn by the fastest trotters available, made numerous runs on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad before steam power was introduced. It was found that one horse could haul on rails a load of freight equal to the effort of twelve horses on a turnpike. Passengers were carried at a speed of twelve to fifteen miles an hour.

The system began with a single line laid between Philadelphia and Columbia. This portion is one of the oldest railways on the American continent. From Columbia a canal followed the Susquehanna River to the mouth of the Juniata River, and thence along the valley of the Juniata to the foot of the Allegheny Mountains. Here began what was known as the Portage Railroad, built across the mountains and consisting of lines laid on inclined planes with level stretches in between. Traffic on the planes was operated by means of stationary engines and cables, and on the level stretches with locomotives or horses. The canal boats were hauled over the mountain tops on this railway after being transferred from the canal to wheeled trucks designed for the purpose. Beyond this remarkable railway another canal linked the system up with Pittsburgh, and so with the head of the Ohio navigation.

The boats were built in sections for convenience in handling and to make their movement overland practicable. Passengers and goods were picked up in Philadelphia, on half a canal boat mounted on wheeled trolleys. The other half of the boat followed behind. Motive power through the streets was supplied by horses or mules. Arriving at the railway terminus the boat sections were transferred to special trucks drawn over the rails at first by horses, and later by locomotives. At Johnstown, which lies on the other side of the mountains, the boats were once more assembled and returned to their proper element, completing the journey on a canal linking Johnstown to Pittsburgh. The whole journey from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, a distance of about four hundred miles, was covered in from four days to a week.

At either end of the line from Philadelphia to Columbia, which was known from the first as the Pennsylvania Railroad, there were an inclined plane and a stationary engine of 60 hp for haulage purposes. The rolling-

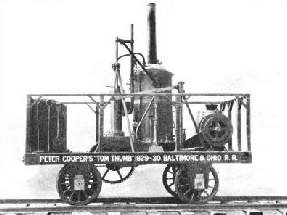

“TOM THUMB” -

In his American Notes Charles Dickens gives an amusing account of his journey from Harrisburg to Pittsburg by this system. The canal boat he describes as being “a barge with a little house in it, viewed from the outside; and a caravan at a fair, viewed from within”. Being in some doubt about sleeping arrangements, he went below, where he “found suspended on either side of the cabin three long tiers of hanging book-

While in America Charles Dickens travelled also by two other early railways, the Boston and Lowell Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The Boston and Lowell line was about twenty-

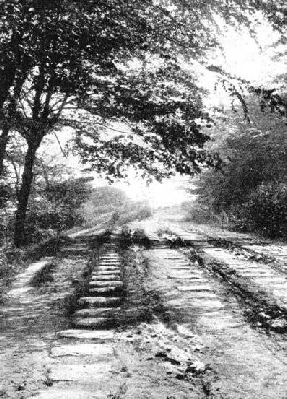

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was chartered in 1827, four years after the first charter of the Philadelphia and Columbia line, but it was not until about 1830 that the first twelve miles were completed. In August of that year the “Tom Thumb” locomotive, designed by Peter Cooper, a New York inventor, made a successful trip of thirteen miles from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland. Subsequently an attempt was made to propel the cars by sails. Then in the summer of 1832 the road received its second locomotive, built by Phineas Davis, of York, Pa., in 1829. This crude engine, drawing two small cars. was unsuited to the work for which it was intended. In September, 1832, a third locomotive was tried, without success. It was not until July, 1834, that there was found an engine capable of hauling the cars, so making it possible to dispense with the horses. It was during the year 1835 that the line reached Washington, and by 1842 it was extended to Cumberland, a few months after Dickens sailed for England. There were four inclined planes on this railway. The first, about forty miles from Baltimore, was 2,150 ft long, rising 80 ft; the next was 3,000 ft long, with 100 ft rise. The line then descended by an incline 3,200 ft long, with a fall of 160 ft; the fourth incline was 1,900 ft long, with a fall of 81 ft. For the most part the rails were laid on granite sills, though some timber sleepers were used.

A considerable number of other railways was chartered, and many constructed, between 1820 and 1840. The Delaware and Hudson Canal and Railroad Company has a charter dated April 3, 1823, but no railway except gravity tracks from a coal mine was contemplated or built in the early years. The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad has a section, the Ithaca and Owego, which was chartered on January 28, 1828; but this was not opened until April 1, 1834. The Paterson and Hudson line was completed in 1834, and the Boston and Providence Railroad in 1835. With these and other developments came a demand for suitable locomotives. Already in 1825 John Stevens, then seventy-

ALL THAT REMAINS TO-

Meanwhile the construction of locomotives was begun in the United States. Apart from the experimental work of John Stevens, the first locomotive built in America was the “Best Friend of Charleston”, constructed for the South Carolina Railway and put into use on that road in 1830. A second engine was made by the same builder shortly afterwards, but these early locomotives were found to be too hard on the light tracks over which they were run, and for a time opinion veered in favour of stationary engines to pull trains through short zones with ropes. Even as late as 1829 a commission of engineers decided that stationary engines were better than locomotives, and they devised a system of stationary engines at points within three miles of one another, the trains to be drawn by an endless rope or chain. But improvements in locomotive design soon put such proposals out of court.

Railway development increased by leaps and bounds, so that by 1850 the United States led the world, with a greater mileage than England and France put together. At the present time the rolling-

In 1933 the US railway mileage was about 258,000, over twelve times that of Great Britain.

You can read more on

“The Story of the Locomotive” and

on this website.