Estonia and Lithuania

Rail travel in two Northern Republics

SHALE OIL is the standard fuel for locomotives in Estonia and makes for economical working. Above is a 2-

THE railways of Estonia are, with few exceptions, owned and managed by the State. The country is one of the republics that have arisen after the war of 1914-

As the country is part of the Great European Plain it does not present many difficulties to the railway engineer. The total area is 18,370 square miles and the population at the census of March 1, 1934, was 1,126,413. Most of the people live in rural districts and are engaged in farming; even a third of those engaged in industry reside in the country. Less than thirty per cent live in towns, and of the eighteen towns ten have fewer than 10,000 inhabitants. About nine-

The railways, confined to the mainland, are of two gauges, the Russian gauge of 5 ft (1.524 metres), and the narrow gauge of 2 ft 6 in (75 cm). The length of lines in April, 1935, totalled 890 miles; of this total 473 miles were broad gauge and 417 miles were narrow gauge. Since 1919 the Estonians have built 255 miles of new lines of both gauges, 362 bridges, and sixty-

In the early period of the new Republic the locomotive fuel was either firewood or shale oil in its raw state. Oil shale is still used in a pulverized form for goods engines, but passenger locomotives burn oil produced from the shale. This oil is very economical, and on this account the train fares are claimed to be among the lowest in Europe. Much of the railway equipment was formerly purchased abroad, but it is now being made in the country.

Passenger traffic amounted in 1933-

The development of oil shale began in 1919 and the output rose from 46,125 tons in 1920 to 588,958 tons in 1934. The shale is worked in open and underground mines, operated by the Government and by private companies. Not only do the oil and shale provide fuel for the country, but also considerable quantities of crude oil and petrol, distilled in the country, are exported. Peat, also developed since the war, is consumed at power stations from which the current is taken all over Estonia.

As there is no coal in the country the development of the industry of extracting oil from shale has solved the fuel problem of the railways. The development of Estonian railways has proceeded methodically and without interruption since the formation of the Republic. After years of warfare the Estonians were faced with the grim necessity of evolving a modern railway system from the ruins of the old.

The story of Estonia is interesting. After vicissitudes including conquest by the German Knights of the Sword, Estonia was under Swedish rule from 1561 to 1710, and under Russian rule from 1710 to 1918. On February 24, 1919, Tallinn, the capital, was freed from Russian Communist troops and independence was proclaimed.

A COUNTRY STATION in Estonia, of modern design. The railways of the country suffered greatly during the war of 1914-

German troops then occupied the country, but after the Armistice of November, 1918, the Germans withdrew. They were followed by invading Russians. A British squadron came to the aid of the Estonians and put an end to attacks by the Russian navy, while the Estonian troops cleared the Russians out of the country. Estonia next had to fight German adventurers under General von der Goltz, who were trying to use the pretext of fighting Bolshevism as an excuse for annexing the Baltic States. The Germans were defeated, an armistice was signed, and a peace treaty was made with Russia on February 2, 1920. At peace after nearly six years of warfare, the Estonians began the work of reconstruction.

Tallinn was formerly called Reval. Founded by a Danish king in 1219 and held successively by Danes, Germans, Swedes and Russians, its history is reflected in its architecture. The population in 1935 was over 140,000, the next largest towns being Tartu with 58,600, Narva with 23,200, and Pärnu with 20,700 inhabitants. Tallinn lies on the north coast; Narva, in the east, is near the Russian frontier, and on the broad gauge line to Leningrad. Pärnu lies on the Gulf of Riga. The first railway in the country was built in 1870 between Tallinn and Narva, as part of the Russian Imperial plan to link Tallinn (Reval as it then was) with what was then St. Petersburg and the capital of Russia and is now Leningrad. The distance from Tallinn to Narva is 130 miles on this broad-

Link with Russia

On the line to Narva and the Russian border the most important junction is at Tapa (forty-

Narva, 130 miles from Tallinn, is an ancient city on the Narva River, with an Estonian castle and a Russian fortress. Above the town the falls of the river provide power for a big cotton and flax spinning factory. In summer steamers go from Narva to the resort of Narva-

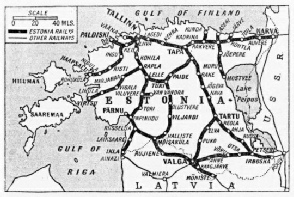

THE ESTONIAN STATE RAILWAYS have 473 miles of 5 ft gauge track and 417 miles of 2 ft 6 in gauge open. The line between Tallinn antl Haapsalu has a short mileage electrified. The first line in Estonia was opened in 187O between Tallinn and Narva.

THE ESTONIAN STATE RAILWAYS have 473 miles of 5 ft gauge track and 417 miles of 2 ft 6 in gauge open. The line between Tallinn antl Haapsalu has a short mileage electrified. The first line in Estonia was opened in 187O between Tallinn and Narva.

The trunk line south from Tallinn to Riga goes east to Tapa and then south through Tartu, to the Latvian border at Valga. After leaving Tapa on this line there is a junction at Tamsalu, nine miles from Tapa and fifty-

from the capital.

The city of Tartu lies in the deep valley of the Emajõgi River, which flows from Lake Wõrtsjärv to Lake Peipus, and before the war was known as Dorpat. The buildings cling to the slopes of the river banks, and the green cathedral hill is laid out as a park. The university was founded by Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden in 1632. The river is spanned by bridges. About a mile from the town is the Estonian National Museum at Raadi, which houses paintings and sculpture. Valga, 169 miles from Tallinn, is the frontier station and is known as Valga E. The frontier runs through a house in the town, as stated in the chapter “Stations and Their Story”. The railway goes to Valk, or Valga L, on the Latvian side of the border, and on to Riga. This line turns south-

West of Tallinn a broad-

Layers of mud, used as a remedy for certain complaints, have been formed on the Baltic coast, opposite the island of Saaremaa. The mud is a soft pulpy mass bluish grey in colour, and its curative properties are due principally to sulphuric compositions. The railways have developed Haapsalu and other resorts by providing an efficient train service. The town has now about 5,000 inhabitants. It was founded in 1228 by the Order of the Knights and contains the ruins of a castle. It is protected from the cold north-

The surrounding country is covered by forests, and the soil is such that fog and dew are unknown, so that the air is dry, and the resort is frequented by visitors in search of health. The most fashionable resort on the Gulf of Riga is Pärnu, a town of 72,000 inhabitants, which is linked with Tallinn by a narrow-

During the war Russian soldiers burnt many of the trees which made up its thirty miles of avenues, but these have been replanted and the resort has recovered its former aspect of trees and flowers. It is ninety miles from Tallinn on the narrow-

The line to Pärnu proceeds past Rapla to Lelle, forty-

UP-

UP-

From Türi a narrow-

Moisaküla is also the junction for a line, forty-

The landscape is varied. The north is a plain covered by forests interspersed with meadows and rivers, some of which are partly subterranean before they reach the Gulf of Finland; two ranges of hills cross this plain. A feature of the north coast is the steep limestone bank which falls abruptly into the sea. In the spring, when the ice of the rivers is thawing, the waterfalls in this region are very beautiful. The shore below the bank is composed of fine white sand. In the south and south-

Tallinn is the chief port, as well as the capital of Estonia. Before the war about 14,000 men were employed in the Russian naval yards and in the railway carriage works, but when Estonia became a republic the Russian work ceased. To-

As one-

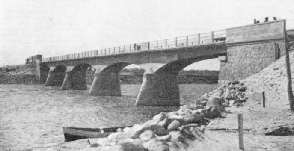

A NEW RAILWAY BRIDGE over the Pärnu River. Since 1919, 362 bridges, sixty-

A NEW RAILWAY BRIDGE over the Pärnu River. Since 1919, 362 bridges, sixty-

The most important river is the Narva, which flows from Lake Peipus. The Narva and other rivers provide a certain amount of power for factories, about 25,000 horse-

The biggest plant is operated by the State at Ellamaa, thirty-

During the winter icebreakers maintain channels of navigation in Tallinn Harbour; the average number of days in the year when the sea is frozen over is forty-

Lithuanian Problems

Though there are few expresses on the Estonian railways, and speed, judged by West European standards, is not high, railway travel is comfortable as well as inexpensive. Most of the trains take second-

It may be thought that the Lithuanian State Railways are simply a counterpart of the Estonian system, in view, of the fact that practically the whole of their system formerly belonged to Russia. But any such view would reckon without the war of 1914-

best they could. Bridges were blown up on the retreat in the approved manner, and things made generally as inconvenient as possible for the advancing enemy. A railway system with no rolling stock is awkward; with some of its important civil engineering works blown up, it is still more awkward. But the Russians had a trump card, namely, the break of gauge. In Belgium, as we have seen in the chapter beginning on page 809, the Germans were able to bring in their own great reserves of rolling stock and locomotives to work the railways in the invaded territory. On the Baltic this was at first impossible, as the German stock would not run on the 5 ft gauge lines.

THIS 0-

THIS 0-

There was no alternative to converting the entire system of main lines to standard 4 ft 8½ in gauge. This the Germans, when they occupied the country, succeeded in doing, with the help of their own numerous locomotives and vehicles. The German Eastern Army was able to march into Lithuania and occupy it, merely drawing on that rolling stock which was in such a state of disrepair that the Russians were unable to move it. It was this which gravely hampered Russia in the war; then, as in the earlier war with Japan, her railway and transport system generally gave way completely, while the Germans were past-

The net result of these warlike activities is that to-

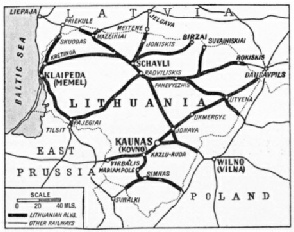

THE RAILWAY SYSTEM of Lithuania consists of 755 miles of standard gauge track and 317 miles of narrow-

THE RAILWAY SYSTEM of Lithuania consists of 755 miles of standard gauge track and 317 miles of narrow-

In Lithuania, as on the standard gauge lines in the south of Latvia, Prussian-

Since the war the Lithuanian State Railways have had a number of fine modern locomotives built for them by the Skoda Works, a well-

Ordinary Lithuanian rolling stock, similarly to the locomotives, is of essentially German design and construction, the passenger coaches consisting of modern and convenient corridor and compartment vehicles. The third-

BUILT FOR LITHUANIA. An unusual 2-

BUILT FOR LITHUANIA. An unusual 2-

So much for travelling conditions. The Lithuanian State Railway system has passed through many vicissitudes, and these did not cease with the end of the war. In 1920, Poland seized the city and territories of Vilna (Wilno), with their considerable mileage of railway. Not only did this lessen the extent of the Lithuanian system, but it also cut a piece out of it, to the great inconvenience of that which remained, for the through Lithuanian line of communications was severed by the “revised” Polish frontier. The break in the railway network was patched up by the construction of the Kazlu-

Another still more recent line, dating from 1932, is that between Kuziai, north-

Gauge Problems

A reference to the map will show the difference that this new line has made to the means of communication between Lithuania’s capital and its outlet to the sea. The tedious journey, over lines arranged in the form of a letter S is now obviated. The traveller and consignments of goods leave Kaunas in a north-

Now, however, the line from Radiviliskis goes through Schavli, with its north-

There is a large number of the smaller towns in Lithuania that are not yet served directly by a broad or a narrow gauge line; a road system links these outlying districts with towns along the route, thus enabling produce from the farms spread about the countryside to be marketed in Lithuania’s towns and in the centres of export.

The railway system consists of 755 miles of standard gauge railway, together with 317 miles of narrow gauge rural light railways. These lines are operated by some 245 locomotives, of which 169 are on the standard gauge main lines. Of the 422 passenger train vehicles, over 300 are standard gauge, while of goods vehicles there are over 3,900 standard gauge and about 500 narrow-

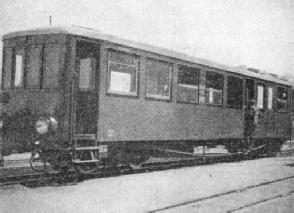

ON LOCAL ESTONIAN LINES Diesel-

ON LOCAL ESTONIAN LINES Diesel-

By reason of her uniformity in the matter of rail gauge with Central and Western Europe, Lithuania is much less isolated than Estonia, though she is in a correspondingly bad position where the broad gauge countries are concerned. In Eastern Europe, the break of gauge in the Baltic States and all down the Polish frontier is being combated by the use of ingenious design of goods wagon, which can be converted from the 4 ft 8½ in to the 5 ft gauge within a short space of time. Such vehicles are owned by the German, Polish, and Russian railways, as well as by those operating in the three Baltic states. In the old days of the Great Western broad gauge in England, the difference was too great to allow for anything of this kind to be evolved in a practical form even had it occurred to anyone. In Lithuania the best trains run at night. After all, slowness on a night train has its compensations over relatively short distances, for it often means that the passenger leaves the train at a fairly comfortable hour in the morning instead of in the small hours. The night express from Kaunas to Riga arrives at Riga at ten minutes to seven in the morning, having left the Lithuanian capital at ten o’clock the previous night. This is not particularly fast running for a distance of only 183 miles; but, for a night journey at least, it has its good points. The express is a sleeping car train carrying first-

Kaunas is 517 miles from Berlin, and the journey takes about thirteen hours by the through sleeping-

The importance of the railways to the Lithuanian can hardly be exaggerated, particularly of the lines leading to Memel, the country’s outlet to the Baltic Sea. Through Memel passes a large part of the Republic’s chief exports, which are bacon, dairy produce, cellulose, timber, flax and livestock.

The Port of Memel

Through Memel also there is a large volume of imports, food, mainly herrings, clothing in the form of textile goods, and large quantities of machinery. Many kinds of raw materials also supply traffic to the railways leading inland from Memel; coal, cement and metals form the bulk of these imports. Kaunas, or Kovno, is an important centre of Lithuania’s railway system.

This city is built in picturesque surroundings on a tongue of land between the Viliya and the Niemen, where the river banks are about 200 ft high. Kovno has a romantic story and is supposed to have been founded about the thirteenth century. The city was the object of considerable strife, in the fourteenth century, between the Lithuanians and the Knights of the Teutonic Order. Lithuania, with Kovno, came under the domination of Poland in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and became the centre of the export trade from the two countries to Russia. The city was plundered and burned down by the Russians in 1655, and at the Third Partition of Poland in 1785 it was annexed to Russia. Kovno forms an interesting link with Napoleon’s “Grande Armée”, which, on June 23, 1812, reached the left bank of the Niemen opposite the city. A hill near a neighbouring village is still known as “Napoleon’s Hill”.

The railways of these Baltic countries are not spectacular in the matter of speed and ultra-

THE INTERNATIONAL SLEEPING CAR COMPANY provides stock on certain of the international trains. On the broad gauge lines there are some 280 carriages in operation, and on the narrow gauge, 139. Above is a typical excursion train in southern Estonia.

You can read more on

and

and

on this website.