The Northern Pacific Railroad

From failure to fortune: the story of a great transcontinental railway

THE NORTH COAST “LIMITED” LEAVING ST. PAUL. Drawn by the latest type of Pacific (4-

AT the dawn of the nineteenth century the settlement of the United States was confined to the belt lying between the Atlantic and the Alleghany Mountains. Between the Mississippi River and the Sierra Nevadas was that vast tract of 883,072 square miles which, in 1803, was sold by Napoleon to the United States for £3,000,000 -

Directly this vast territory came under the Stars and Stripes a keen anxiety to explore its innermost parts became manifest. Many expeditions were organised, but only one matured -

The most popular project was to follow the two great rivers, the Missouri and the Columbia, to their respective headwaters on the eastern and western slopes of the Rocky Mountains, which, it was pointed out, would need only a short length of intervening rugged country to be bridged. Every traveller who succeeded in crossing the country by pack-

However, the scheme languished until 1844, when it was taken up in grim earnest by Asa Whitney. He was a man of wealth, and he devoted all his energies and resources to arousing public interest for the construction of a northern transcontinental railway. He was assailed on all sides by hostile criticism, but he fought tenaciously until, having frittered his whole fortune away in propaganda, he retired from the scene to eke out a humble existence as a milkman for the remainder of his days.

But Whitney’s work had not been in vain. He had infused others with his enthusiasm, and among these was Edwin F. Johnson, of Vermont, who, being a clever engineer, with a big reputation, was fitted to the task. He was very aggressive, and although he did not escape criticism, extreme care had to be displayed by detractors in attacking his proposal, inasmuch as he tore technical objections raised by laymen to shreds. Johnson hammered away at the project until at last he forced the Government to sanction that momentous enterprise, the Pacific Railway Surveys, which was carried out by the foremost topographical and military engineers of the time. Five expeditions were dispatched to the coast, each being allotted a section of the mountains which it was commanded to probe through and through, to find the easiest route for a railway. These labours are summarised in thirteen bulky volumes, which have an honourable and undisturbed resting place in the archives of the Government. They are fine pieces of work so far as they go, but the railway builder of to-

When these reports were submitted to the Government in 1855 they aroused widespread interest, and formed a perennial topic of idle parliamentary debate for another six years. But in 1862 matters came to a crisis; academic discussion was brought to a dramatic end. The State of California demanded railway communication with the Eastern States; if this request were not met, it would secede from the Union. Faced with the possibility of disruption, Congress was stirred to action, and sanctioned the building of the Union and Central Pacific Railways, to constitute the first transcontinental steel highway across the country.

But this decision was at the expense of the cause which Whitney and Johnson had espoused so valiantly, and, as may be supposed, the Government decision inflamed these interests. Johnson became uncompromisingly aggressive, and, as he had a large and influential following, the position of the Government became somewhat perilous. Finally, to appease the advocates of the northern route, and to satisfy public opinion, the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad was sanctioned, the Act being signed by President Lincoln on July 2nd, 1864.

The fathers of this enterprise were jubilant. They had won the day, and completed preparations to “make the dirt fly”. Johnson was given the reins of the undertaking, and under his banner was enrolled a corps of the finest engineers in the country. The surveys were run and the location decided; everything was ready to start. But there arose one insuperable obstacle: whence was the money coming to finance construction?

Then came the Civil War. The railway project was blown sky-

EARLY LOCOMOTIVE AND ROLLING STOCK, showing cheap timber trestle construction.

This in itself was a stupendous piece of work. In 1870 the territory which was to be penetrated by the new transcontinental boasted only 600,000 people, of which the State of Minnesota alone claimed 400,000. The remaining 200,000 were divided into small communities scattered here and there over territory which was the home of the Indian, the buffalo and other animals. Montana did not possess a sheep or a cow; North Dakota was a silent wilderness; Eastern Oregon and Washington were the haunts of the bear and trapper. In view of such conditions it is not surprising that timidity was displayed by investors; that Jay Cooke’s attractive statements were regarded with suspicion; and that carping critics wanted to know whence the railway was to derive its traffic.

Yet the financiers and railway forces were not dismayed. With the money which was harvested 2,000 navvies were set to work in 1870 with their shovels, picks and wheelbarrows at a point twenty miles west of Duluth, Minnesota, their eyes being turned towards the Pacific. The metals were brought up from the mills and discharged at Duluth at £18 per ton, from which point they had to be hauled to the grade as circumstances permitted. By the end of the year the winding ribbon of steel had been laid to the banks of the Red River in Minnesota. Simultaneously the forces toiling on the western arm, which was to advance eastwards from the Pacific, had been busy, the first sod having been turned on the banks of the Columbia River near Portland.

Once started, work went ahead, although money was tight. Congress was asked to assist, and in 1871 consented to the company mortgaging its road and land grant. The plains were traversed as far as Bismarck on the Missouri River, while the line had been carried from Portland to Tacoma, when came the great financial crash of 1873. It caught the young railway at a disadvantage. The statements which Jay Cooke and Company had circulated concerning the possibilities of the country penetrated were assailed vigorously. So-

“Sell! Sell! Sell!” This was the advice the investigators wired back to their investing friends in the cities. At that time there were 13,000 stockholders in the company, and no astute manipulation was required to precipitate a panic among them. The stock was thrown pell-

Construction was brought to a standstill. Not another penny could be raised. The adverse reports which had been circulated were too damning to release the purse-

THE NORTHERN PACIFIC TRANSCONTINENTAL EXPRESS climbing the 116 feet per mile grade through the Rockies with a “double-

After the smash a stand-

There was one popular fallacy which held the country locked firmly against agricultural expansion. This was the impression of the prairie winter, which was said to be a nightmare. Certainly the icy blasts from the North have a clean sweep of several hundred miles over country as level as a table-

Unfortunately the railway management made no effort to dispel these fears; rather they supported them. When the last bushel of grain had been loaded into the railway truck and dispatched to market, all locomotives, wagons, and men on the prairie were withdrawn. The company concluded that it was better to close down the railway for five months or so rather than face the fury of winter.

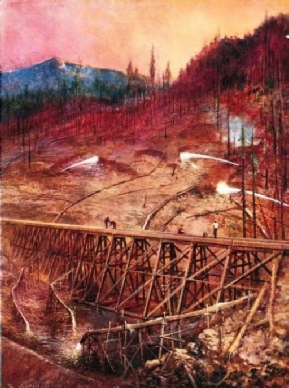

FILLING UP A TRESTLE: the monitors at work washing down the hillside.

These illusions prevailed until they were dispelled in a somewhat unusual manner. The Sioux Rebellion of 1876, the massacre of Custer and his little band, and the general insecurity of the country arising from the success of the Red Men stung the Government to drastic action. The railway had reached the east bank of the Mississippi, and Bismarck, at the railhead, had become an important strategical centre. The Government completed its plan of campaign; Bismarck was to be the base. As it was essential for the War Office to be in close rail and telegraphic communication with the front, the railway company, after the harvest of 1876 had been garnered, was asked to refrain from withdrawing its men and rolling stock for the winter, but to keep the line open for military purposes.

The Government traffic was somewhat heavy, and Nature, as if determined to aid the refractory Red Men, hurled its forces -

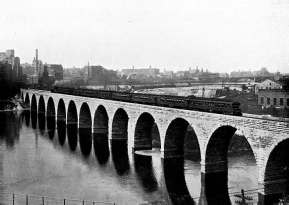

In 1879, the railway having retrieved its position somewhat, financial aid was forthcoming, and construction was resumed. On the eastern section the broad rolling swathe of water of the Mississippi River had to be crossed. This demanded a massive metal bridge, 1,400 feet long, divided into three spans, with the railway track placed 50 feet above the water. By the time this was completed £200,000 had gone -

On the west coast the railway was pushed forward just as rapidly, although there, owing to the Cascades disputing advance, progress was less marked in point of distance. Huge rifts in the mountains had to be spanned, and these were overcome by erecting massive timber trestles, for which millions of feet of lumber cut in the vicinity were used. The humps of the mountains were trimmed back to provide a narrow causeway for the metals. The turbulent mountain rivers were spanned by heavy wooden bridges and trestles, everything being carried out upon pioneer lines to reduce constructional costs as much as possible.

While tunnelling was reduced to the minimum, it could not be avoided entirely. Two heavy works of this character were required to get through the Rocky Mountains. In both cases the rock put up a stern resistance, so that several months passed before the Bozeman Tunnel, 3,610 feet long, and the Mullan Tunnel, of 3,847 feet, were pierced. Simultaneously with the driving of the main line from each end, short spurs were laid down into promising districts for mining, lumbering, and agricultural development. In nearly every instance the branches resembled the main track, inasmuch as they preceded the settlers, so that a period of some years of unproductiveness had to be faced before any profits were likely to accrue.

THE NORTH COAST “LIMITED” crossing the bridge spanning the Mississippi River, which divides the twin cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

The vigorous energy with which construction was maintained when the engineering forces once more settled down to their stride was due to the tireless activity of Mr. Henry Villard, who assumed control of the railway, and who, having built up a commanding railway managing reputation in the West, was fitted to the post, which, under the stringent monetary conditions, was somewhat onerous. Villard was a born railway administrator, of strong character and remarkable foresight, who commanded the unbounded confidence of powerful financial interests. He had been associated with Mr. Thomas Alva Edison, and, in 1881, when the Wizard of Orange was experimenting with his electric railway at Menlo Park, for the construction of which Villard was primarily responsible, and in which he sank his own money, he discussed with Edison the electrification of the Northern Pacific through the Rocky Mountains. When it is remembered that at this date electric railway working was in its infancy, when not more than 2½ miles of electric railway were in operation, and that as an experiment, the idea of applying this motive power to a section of a transcontinental railway was somewhat daring. But Villard maintained that electric operation would be cheaper than steam, and that it was certain to be used for the mountain sections of big railways at all events, since adequate energy is generally available from the mountain torrents.

Villard also trusted his engineers implicitly -

THE OLD AND THE NEW, NEAR LAPPINGTON.To the left is the original bridge built of wood. The old line was abandoned when the new, straight and more level track was finished.

THE OLD AND THE NEW, NEAR LAPPINGTON.To the left is the original bridge built of wood. The old line was abandoned when the new, straight and more level track was finished.

The most sensational display of engineering on the whole line, however, was the driving of the Stampede Tunnel, to overcome the Cascade Mountains. The route across this obstacle had been a matter of discussion among the officers of the company since the first spadeful of earth was turned in 1870, and for eleven years the question was debated as to which pass through the range should be followed. The surveying engineers narrowed the issue down to a choice of three -

The decision was left almost completely to Mr. Virgil G. Bogue, who at that time was chief assistant engineer. He had been spying through the mountains for years, being responsible for the mountain division of the railway. Through his energy the Stampede Pass was discovered, he having sent a party through the mountains over this route, when no knowledge of such a gateway existed. Mr. Virgil G. Bogue is one of those great railway engineers who have been created by railway building in the western United States, who at a later date provided the United States with its easiest and fastest transcontinental railway -

In 1884 Mr. Bogue recommended the adoption of the Stampede Pass, and outlined a tunnel nearly 2 miles in length, which he estimated could be completed in twenty-

FILLING IN A TRESTLE BY HYDRAULIC SLUICING. Building an embankment with material washed down from the mountain-

FILLING IN A TRESTLE BY HYDRAULIC SLUICING. Building an embankment with material washed down from the mountain-

The contractor hustled. His bid was accepted on January 21st, 1886, and he had undertaken to complete the tunnel by May 21st, 1888. Leaving the Northern Pacific Railroad offices in New York with his contract, he at once ordered all the plant required, at the same time wiring to his general manager in the west to gather an army of men and to cut roads from the railheads to the tunnel site. What this meant may be gathered from the fact that a wagon-

An advance army of men were got on to the tunnel site with as much speed as possible, and they commenced driving the bore 16½ feet wide by 22 feet high through the detritus on each side. In this preliminary work two mountain streams had to be diverted, one of which fell in a beautiful cascade across the eastern portal from a height of 170 feet.

While the tunnel faces were being excavated the railway engineers appeared on the scene to lay a temporary track over the range. This in itself was an amazing piece of work, comprising a switchback along which the trains were pushed and pulled from level to level over grades running 300 feet per mile. Standing at the top of the western zig-

Owing to the difficulties encountered in reaching the portals six out of the twenty-

No effort was spared to maintain the scheduled rate of advance. But when water burst in, and caused the rock-

REBUILDING IN STEEL THE OLD TIMBER TRESTLE ACROSS GREENHORN GULCH IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS. Lowering a 61 foot girder from the cars.

The bore was driven from a centre heading, from which it was widened out subsequently to its full dimensions. An ingenious machine was devised to facilitate work at the heading. It was like a big table, straddling the full width of the tunnel, with its legs mounted on two-

As the time-

On May 3rd, 1888, eighteen days before the expiration of the contract time, the last piece of rock was broken down, permitting the opposing drilling forces to shake hands with one another. Eleven days later the excavation was completed. Two days after the metals were laid from end to end, and on May 21st, the contracted date, Bennett handed over the work to the railway, the first regular train running through the bore on May 22nd. As a tunnel-

When the completed line settled down an era of prosperity appeared to be assured. Settlers were pouring into the country, and were developing the land contiguous to the main line and its spurs. The rolling stock had grown in 1883-

The Northern Pacific Railroad enjoyed seven years of indisputable plenty, and appeared to be established upon a firm footing. By 1899 the gross revenue had increased to £5,000,000 per annum, and the operating expenses had been reduced to 47 per cent, of the gross earnings. Unfortunately, however, owing to the exceptionally heavy cost of construction, the fixed charges became a mill-

Then came a heavy fall in the traffic; the United States, with its characteristic capriciousness, was hit by another financial stampede, and the Northern Pacific Railroad was dragged down in the disaster of 1893. It was a sorry trick of fortune, but this enterprise appeared to be dogged with ill-

Villard was so stupefied by the magnitude of the financial catastrophe that he would have gone under had it not been for Edison. The inventor was asked to cheer up the broken railway magnate, and only succeeded in achieving the desired end by discussing with him the electric light, which just then was coming into its own. Villard had backed Edison against all antagonistic argument concerning the electric railway, and the inventor now had an opportunity to reciprocate. He urged Villard to throw his energies into the exploitation of the electric light. The ruined financier took his friend’s advice, regained his feet, and amassed a new fortune.

The receivers continued the overhauling and improving policy which had been taken in hand before the crash. On September 1st, 1896, the Northern Pacific Railroad, valued at £65,000,000, was sold under foreclosure proceedings to the Northern Pacific Railway Company, and as such it is known to-

The third attempt to render this transcontinental highway a railway power in the land has met with conspicuous success. Now it is one of the greatest roads on the continent. The new blood, not satisfied with the condition of the property, went over it from end to end, eliminating all adverse grades and curves, strengthening bridges, re-

As in the case of the Canadian Pacific, the sheet anchor of this American transcontinental railway throughout its varying fortunes has been the grant of land, which averaged so much per mile. The construction of the railway brought some 45,000,000 miles into its hands for sale, and the peopling of this vast territory not only has swelled the receipts, but virtually has ensured a traffic income, since the line handles practically the whole of the necessities and produce of this adjacent population.

Subsequent events have served to substantiate the contentions of the fathers of this transcontinental, and also the statements that were issued by the banking firm of Jay Cooke and Company respecting the possibilities of the country traversed. The land which at that time could not find purchasers at 6d. per acre now commands from £15 to £120 per acre. The tributaries of the Northern Pacific Railway ramify in all directions through the west in the interests of holiday-

THE NORTH COAST “LIMITED” REAR VIEW, showing the observation car.

You can read more on

and

and

on this website.