The Union Pacific Railway

The Early Years of the First of the Transcontinentals

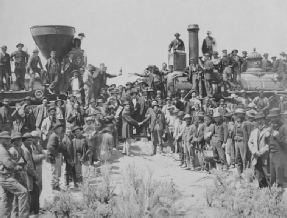

THE CELEBRATION following the driving of the “Last Spike” at Promontory Summit, May 10, 1869

MUCH as life in the British Islands is bound up with the railways that cross them in all directions like the meshes of a huge net, the influence of the iron way has been even more felt on the other side of the Atlantic. For whereas in Britain the country has made the railway, in the States the railway may be said to have made the country, being the precursor of civilisation in waste and barren places, and not merely the most beneficial means of communication in districts already opened by roads.

Any literary work that deals with the expansion of the United States can no more avoid references to the rise of the great railway tracks than the traveller in the land of the Stars and Stripes can get from point to point without calling in the aid of the locomotive. In fact, so mightily has the invention of Trevethick grown and prospered under western skies, that the stories of the railroad and the American people are intertwined in a manner that is without parallel in any other country of the world. And the same enterprising spirit that has raised the United States in a comparatively short time to a foremost place, both industrially and politically, among the nations, has also signalised them as in many ways the scene of the most marvellous advances in the science and practice of mechanical locomotion.

The writer of a series of interesting articles in the Times -

“In Great Britain the era of railways followed the era of highways. The towns were settled, vested interests in real property were respected by the law, and land for railways in a country of such circumscribed dimensions could, in most cases, be obtained only at a very considerable cost, and, it might be, after a heavy outlay for Parliamentary and other expenses. At the outset, too, the promoters had to meet not only active opposition, but the full force of popular prejudices of the bitterest kind; while, quite apart from this, it has always been regarded as a matter of course in Great Britain that a railway company was an organisation out of which every individual who had the chance might squeeze the uttermost farthing. Then, again, the British companies have been forced, either by law, by the requirements of the Board of Trade, or by the powers possessed by the various district authorities, to construct their lines in the most substantial manner. . . . In the United States, on the other hand, excepting only the case of New England, the railways preceded the settlement of districts and the building up of the towns. They generally made the roads along which population was to follow. They were, in fact, the pioneers of national development.” (1)

Though money was not so plentiful in the States as in England, the promoters of railroads had great advantages in the huge supply of timber available for conversion into sleepers and trestle bridges, and in the readiness that Government showed to give them land all along a projected route, and even to help them financially, by guaranteeing a part of the constructional expenses. The avenues created for the movement of population proving, in most instances, what the country wanted, the free lands of a Company soon increased in value, and their sale enabled the vendors to set their system in better order than was possible in the first instance, when economy demanded the laying of a track such as, in England, would horrify a Board of Trade Inspector.

Competition and speculation in railways were by no means unknown in the United States, and their results were sometimes as disastrous as in the British Isles. “Many (systems) got into a deplorable condition. Where little or nothing had been spent on them since their construction, they practically required to be rebuilt at the end of eight or ten years. In one instance an engineer who was inspecting a line that was being taken over by another Company kicked down with his foot a thoroughly rotten piece of timber forming one of the supports of a trestle bridge over which a train had passed only a few days previously.” (2)

After a period of speculation there naturally followed one of panic; and about the time of the Civil War railways in America experienced a good “shaking up”, out of which they emerged in a more stable condition, and better organised for a policy of expansion. That they should expand rapidly was felt to be a political necessity, as the war had proved that the States were really not one or two countries, but a number of countries, distinct in their populations, ambitions, and resources. For welding them together into anything like an harmonious and mutually supporting whole, one thing was particularly needful -

It is impossible in the scope of a few pages to even refer to the hundreds of eastern systems of the States. Not that they are without their romance, for here, as in other countries, their creation has been accompanied by many a thrilling adventure, and by constant fights with Nature. We must confine ourselves to a consideration of the mighty tentacles that spread from their western centres to the Rockies and the lands beyond.

A glance at the railway map of the United States will be profitable and instructive to one whose knowledge of the geography of the country is derived mainly from the dry details painfully accumulated in the school classroom. From St. Paul, on the Mississippi, the Great Northern reaches across to Seattle, on Paget Sound, Washington. One hundred and fifty miles south, on the average, runs the Northern Pacific, from the same eastern terminus, to Portland, Oregon -

To-

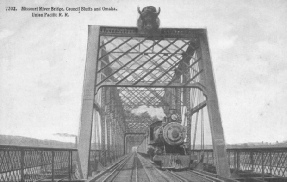

MISSOURI RIVER BRIDGE, Union Pacific Railway

The first line built right across the States from the Missouri to the Pacific resulted from the private enterprise of a few small merchants of Sacramento, California. They, in 1861, organised the Central Pacific Railroad Company (now merged into the Southern Pacific) to carry the metals eastwards to the limits of California, where they should meet the platelayers working westwards from the Missouri, over the track now known as that of the Union Pacific Company. The project was formidable enough, including as it did the crossing of the Sierras at an elevation of 7000 feet or more, and a plunge into the great territory, 1400 miles long and 1300 miles wide, which as late as 1850 was still marked as “unexplored desert”; a tract so unknown to the Yankee, that in one stretch of 665 miles there lived but one white man. The cross-

The Sacramento merchants found support in the public opinion of the Eastern States, where bright dreams were being dreamed of the great possibilities for trade with China and Eastern Asia that would be opened by transcontinental rails. A strong feeling was also forming itself on a political basis, since the unsatisfactoriness of the isolation of the Pacific States became more and more apparent in the unsettled times preceding and continuing throughout the Civil War.

A Bill was passed through Congress in July 1862, assuring both the Central Pacific and Union Pacific of Government support, and a commencement was made in the same year at the Pacific end. Eastwards matters hung fire. Money was “tight”, and the desert did not seem very attractive either to capital or labour. Consequently the charter, with its subsidy and land grants, fell somewhat flat, none of the railroads which, as President Lincoln imagined, would be benefited by the scheme coming forward to take a hand. They declared that they saw no prospects in a railroad across the desert. Individuals made desperate efforts to collect sufficient capital for a beginning, in the hope that when once things had been set in motion, money would come in. But to little purpose; and not till after the passing of a second Bill in 1864, which doubled the land grant and offered a subsidy of 16,000 to 48,000 dollars a mile of track, could a start be made at the Missouri end.

DALE CREEK BRIDGE, Union Pacific Railway. Completed in April, 1868, it presented engineers with one of their most difficult challenges.

Among the engineers of the line was one Grenville Dodge, (4) who, as early as 1853, had been over the Iowa and Nebraska country, surveying and looking about for the best route for a railway. On more occasions than one he found himself in danger of annihilation, by the Indians, who then were mighty in the land. He pushed up the Platte River and across the plains as far as the Rockies, and took a liking for “South Pass” as the proper gate to a terminus on the Pacific, which he fixed at Portland, Oregon. In an interview with President Lincoln in 1863, he gave it as his opinion that the Union Pacific should at least start from Omaha, on the left bank of the Missouri opposite Council Bluffs.

Here, accordingly, in 1864 the first ground was broken for the Union Pacific Railway. At the commencement operations were much hampered by lack of transportation, as no railroad as yet reached the Missouri near Omaha, and all material had to be brought, at enormous cost, up the river from St Louis. And even when considerable progress had been made, and people began to talk of the great future of the road, the granted lands did not sell well enough to cover current expenses, though the subsidy was paid as soon as a section had been completed. The Company was also seriously annoyed by the hostility of the Indians. These were ever with the surveyors going in advance of the construction trains. Many a promising young engineer found a grave in the prairie. Nor did the Sioux hesitate to attack the plate-

Yet the “rail-

IN THE EARLY DAYS of the Union Pacific Railroad. This photograph is of a replica of a Union Pacific train in the middle ‘sixties. The wooden coaches had especially narrow windows so as to offer as small as possible a target to Indian arrows and bullets. Each train carried a community stove, where cooking was done. Bedding, if any, was owned by the passengers.

(1) The Times, January 5, 1903

(2) The Times

(3) The Times, April 10, 1903

(4) Afterwards General Dodge, and a prominent railway man.

You can read more on

“The Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway”,

“The Pennsylvania Railroad” and

“The Union Pacific Streamlined Express”

on this website.