The Railroads of Japan

Steel highways in the land of the rising sun

LOVELY JAPAN. An express train drawn by a “Pacific” type engine passing through the Japanese countryside in the island of Honshu. Mount Fuji-

THE area of the Japanese Empire covers more than a quarter of a million square miles. It has a population of more than 60,000,000 people. Yet its railway system is of only comparatively recent development.

Until 1872, the palanquin -

But progress was slow. In 1887, fifteen years later, the total number of passengers carried on the Japanese railways was only 5,919,383 -

This sudden increase in 1907 was probably a result of the Government’s decision to nationalize all the railway systems in the country, except a few local lines.

Despite the rapid progress of the last twenty-

This first engine was built to the order of the Japanese Government by the Vulcan Foundry at Newton-

A Tribute to Britain

The story of the early days of the Japanese railways is a great compliment to British engineering skill. British engineers were responsible for the surveying and construction of practically all the important systems, while British officials and drivers were employed for a number of years in key positions on the railways.

Even now, when the Japanese build and control their own railways and locomotives, British influence can still be felt. Many of our own terms, such as “pointsman” and “signal-

Great Britain has therefore played an important part in the development of Japanese railways. It was an Englishman, Horatio Nelson Lay, who came forward with a proposal to furnish the required funds for the first railway. In 1869, half a million yen (approximately £50,000 at par) was needed towards financing the project of laying a trunk line to connect Tokyo with Kyoto and Kobe, together with important branches to Yokohama and to Tsuruga. This amount had been promised by the State treasury to forward the construction of the initial stage of the work between Shimbashi (Tokyo) and Yokohama, but later the treasury found that it was not in a position to make the outlay, while private capital declined to venture in this novel field of investment. Lay thereupon stepped into the breach. His terms were accepted, and a Japanese loan for one million sterling was successfully placed in London.

The Japanese have not forgotten this English influence. Their gratitude to this country can be summed up in the words of Mr. M. Shimoda, of Osaka. “To onlookers,” he said, “Japan’s progress in recent years may appear to be marvellous. But we remember we owe almost everything to England. We hope the British people will always look on us as students and younger brothers”.

Every year railway officials visit England so that they can keep in touch with railway development.

From the outset the British engineers sent out to supervise the work found themselves faced with almost insuperable difficulties. They soon discovered that Japan was not suited to railway construction -

As a result of the preliminary survey, the original plan to link the northern and southern capitals had to undergo drastic revision. For military reasons, the Japanese were anxious for the line to take a middle course -

The only alternative was to follow the Tokaido, the great highway of Eastern Japan, which skirts the coast along the narrow strip of flat country intervening between the foot of the hills and the Pacific Ocean. This route was open to the possibility of an attack from the sea side in time of war, but the less mountainous nature of the country to be traversed forced the Japanese to agree to its adoption, despite its strategic shortcomings.

The Shimbashi-

Beneath the River Bed

The river-

This method of tackling the trouble, although a good one and still adopted in present-

The gauge adopted for these sections was one of 3 ft 6 in, which has since become the standard gauge of the Japanese railways. When completed, these sections formed practically the nucleus of what now constitutes the Tokaido line, one of the main arteries of railway traffic in Japan.

In 1880 the Kyoto-

Meanwhile, a survey was made in the large northern island of Hokkaido, on the Otaru-

ALONG THE COAST of Japan at Amarube, the San-

About this time the Government was involved in financial difficulties, and the construction of state-

The nationalization of railways is frequently discussed in Great Britain, and it is interesting to see how the scheme has worked in Japan. Without entering into any controversial discussion on the merits or demerits of nationalization in general, it must be said that in Japan it is an unqualified success.

To-

In the event of a national emergency, the railways are used at once. In March, 1922, for instance, when severe and disastrous earthquakes occurred in north-

In Times of Peril

When any disaster of this nature occurs -

All this is done without delay, and is typical of the organization that controls the greatest railway system in the Far East. It is an organization that is both self-

The State Railways has its own laboratory, known as the Railway Research Offices. This is one of the leading technical laboratories in Japan, and its work is concerned mainly with the standardization of designs and measurements, but it has also made many important discoveries. Its work includes tests for prevention of rust on steel, studies of water for use in locomotive boilers, and tests on rustproof paint for steel.

On one occasion the Railway Research Office received a report that the exhaust nozzle of a triple valve on a goods wagon air brake was frequently put out of service owing to its being choked by bees’ nests. After repeated tests, a new paint which would keep bees away was invented.

This same department devised a unique means of inspecting the railway lines. This was a magnetic rail-

When the results of any discoveries apply to goods traffic -

So that this interest shall be maintained the State Railways has created facilities for cheap travel, with the result that the Japanese have become great users of the railway. They have quickly availed themselves of these cheap rates to see the beauty spots of their enchanting land, and to make pilgrimages to famous shrines and temples at great distances from their homes.

THE APPROACH TO TOKYO, the capital of the Japanese Empire and the headquarters of the railways. To the left of the picture large rolling-

The annual pilgrimage to the shrines of Ise, for example, attracts immense crowds, and many special trains are put on for the occasion. Even so, overcrowding cannot always be avoided, and this is not surprising when it is realized that the railway sometimes has to cater for pilgrims who have been granted special terms for parties of from ten to three hundred.

Another festival which is a challenge to the efficiency and organization of the State Railways is the annual Buddhist festival at the Hommonji Temple, at Tokyo.

Some of the shrines and temples are situated at places that are inaccessible to the ordinary railway. To overcome this the State Railways has built a number of funicular railways. The first to be built was up a mountain called Maya-

But excursion tickets apart, railway rates generally are extremely low. It is possible to travel first-

The dining-

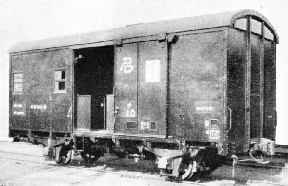

A LIVE-

Along every line various stations are noted for the excellence of their o bento, especially when some esteemed local product is procurable. In one of these boxes, costing forty sen (approximately tenpence), there is enough food to satisfy any man’s hunger. After o bento the next best value for the native passenger is o cha. Five sen (about a penny) buys tea, teapot, and cup.

In spite of the rapid advance of the railway, and of commerce in general, Japan remains “the land of the lotus and the cherry blossom”. Nothing has been allowed to spoil the natural beauties of this interesting and enchanting country.

With the ideal of promoting mutual understanding between nations, and because of the economic benefit to the country, the State Railways makes special efforts to attract foreign visitors to Japan.

The activities in this direction are world-

This aspect of railway work in Japan is considered of such importance that a special department -

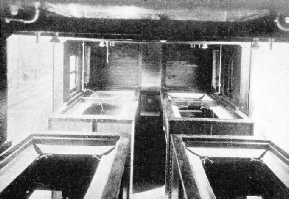

THE INTERIOR of a live-

The Japanese possess an infinite capacity for taking pains, and this characteristic has stood them in good stead when catering for visitors from other lands. Everything has been done for the comfort of tourists visiting Japan. The State Railways has opened hospitals at many of the large railway centres, while most stations have a competent medical staff, so that any passengers feeling unwell can receive immediate attention.

The State Railways also owns two hotels, which are noted for their courtesy, cleanliness and comfort. These hotels are at Shimonoseki and at Nara.

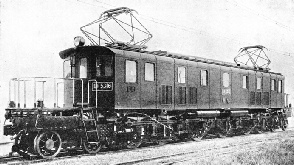

In their efforts to be up to date, and because of the different nature of the various districts, practically every type of railway transport in the world has its counterpart in Japan. Electricity has been tried with success. The district of Ochanomizu-

Japan has experimented over a number of years with Diesel locomotives. These have worked satisfactorily, and their number is likely to be increased in the near future.

Earthquake Dangers

Even the Underground system has not been neglected. There is a short system known as the Tokyo Railway. Further development is improbable, because the menace of earthquakes compels even the great cities to retain the sewerage system, of a small village, and the instability of the earth practically rules out this form of transport.

But the fact that the Japanese have, in the face of this difficulty, experimented with an underground railway is a tribute both to their courage and resourcefulness.

The same courage and resourcefulness have helped to plan ways and means of surmounting the many natural obstacles. Every one of these obstacles has been overcome, chiefly because of skilful and patient engineering work.

The line that runs between Yokokawa and Karuizawa is an outstanding example of this. It leads over a steep mountain pass called the Usui Pass, and the inclination is 1 in 15 for a length of five miles, three miles of which are in tunnels all cut through rock. The train is taken up the pass by “Abt” engines, which have a cogwheel working on a rack-

But the problems that face the railway engineers of Japan are not confined to those arising directly from the building of their railways. There is always the menace of the earthquake.

In 1923 one of the worst earthquakes in history shattered Tokyo and its port of Yokohama. The catastrophe claimed 150,000 lives, and destroyed 5,000,000 homes. The material loss of all kinds -

To-

The Japanese have taken every advantage of recent developments in locomotive design. Although some of their original locomotives are still in service, this does not mean that there are no modern engines.

Most of the modern locomotives in Japan are a combination of British and American designs. The sand boxes are on top of the boiler. Another prominent feature of many of the locomotives is the large tenders which they draw. This is to enable the long-

AN IRON “MIKADO”. One of the latest type of engines used on the Japanese main lines. These engines, of the 2-

Another interesting feature of Japanese locomotives is that some trains have double smoke-

We have seen in this chapter the attention given to every detail to ensure that all travellers shall be comfortable. The same attention is given to goods traffic, which, we know, provides the greater revenue.

The increase of goods traffic in Japan made it necessary to have a more powerful type of locomotive, and an American firm was trusted with the task of building it.

IN THE SUBURBS. The network of electrified lines is steadily increasing, and to-

This firm took the established “consolidated” type of the 2-

This is merely one example of the manner in which the Japanese exploit their chief source of revenue on the railways, and many others could be quoted. Some of these are peculiar to Japan, which, as stated, has to contend with many unusual difficulties.

A great part of the goods traffic is of an unusual character -

Dry Ice

Perishable goods, such as fish, butter, and meat arc carried in refrigerator cars, fitted with dry ice. This is ordinary ice kept at such a temperature that it has no moisture. It was believed that its use in refrigerating cars would go far to improving the existing method of the transport of perishable goods, and the State Railways decided to employ it for a trial in fifteen cars. These test cars were specially remodelled, and after repeated experiments it was found that the use of dry ice was not only a better safeguard against bacteria, but that it was also specially suited for this form of transport.

THE SWALLOW or “Tsubame”, one of the most famous expresses in Japan. The photograph shows an animated platform scene and the observation car at the back of the train.

THE SWALLOW or “Tsubame”, one of the most famous expresses in Japan. The photograph shows an animated platform scene and the observation car at the back of the train.

In this and in other ways Japanese business houses are encouraged to send their goods by train. This encouragement is not merely an appeal by way of advertisement. The State Railways has made the business man feel that it is the best way to send his produce, and that it is to his own advantage to do so.

These advantages are not limited to his own country. If he should want to send his goods to an exhibition abroad, the State Railways allows him a special reduction in rates for the transport of goods to be displayed. In 1933 many large firms in Japan took advantage of this offer to send their goods to two of the largest trade fairs ever held, at Chicago and at Leipzig. A reduction of 40 per cent off the regular rates was allowed for goods carried over the State lines.

Another great advantage to business men is that they can store their goods at the State warehouses. The first of these was opened in October, 1931, at Akihabara Station, in the city limits of Tokyo. This proved to be so successful that the warehouse could not always comply with the demands of the depositors, and it had to be considerably enlarged.

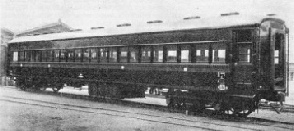

AN OBSERVATION CAR used on the Japanese main lines. This type of care has specially wide windows to afford views of the countryside, which is mostly of a mountainous nature.

A criticism frequently levelled against the nationalization of railways is that it makes for a monopoly which, in its turn, makes for autocracy and dictatorship. This criticism is inapplicable so far as Japan is concerned.

At one time, for example, the operation of a goods train, no matter whether it was in “regular” service or not, was often suspended because the volume of goods to be carried was so small that it did not justify an immediate journey. This was, of course, a considerable hardship for those unfortunate consignors who had chosen that particular day for the transport of their goods. Representations were made to the State Railways, with the result that now certain goods trains do their regular trips whether they have a small volume of goods or not.

In spite of the eagerness on the part of the Japanese to be up to date, they do not neglect to safeguard their trains, all of which are controlled by the block system explained in an earlier chapter. The latest block system is mainly adopted in single-

AN ALL-

This account of the railways of Japan proper would be incomplete without reference to her overseas systems, which she developed without foreign supervision. The first was the State line in Korea, which dates back to 1890, when a railway linking Seoul with Chemulpo was laid and opened to traffic by the Keijin Railway Company.

Japanese Rivalry

The outbreak of the Russo-

The work of construction was steadily pushed on, and in 1910 the Keijo-

The large island of Formosa, another Japanese colony, did not enjoy proper railway facilities until its cession by the Chinese Government, for, prior to that time, the only railroad was a small light railway between Keelung and Shinchiku. Soon after the cession, work was begun on a line to link Takao with Keelung at a cost of 28,800,000 yen (approximately £2,880,000); it was finished in 1908. This now forms the trunk line in the island's system of communication. Following this, the Choshu and other systems were built, so that the total length of Government lines now operated reaches 549 miles.

Manchoukuo is the latest field for Japanese railway activity. As with the South Manchuria Railway, the ownership and operation of the systems are regarded by the Japanese as of great importance in developing and colonizing the region.

This chapter is necessarily a brief survey of a railway system which is not only the largest in Asia, but which also challenges comparison with any other system in the world. This survey is, however, enough to show that in railways the Japanese are in no way inferior to Western nations.

ONE OF THE MANY ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVES serving on the Japanese lines. During recent years the number of miles covered by electric trains has more than doubled, and nearly 700 miles of track formerly served by steam trains have now been electrified.

ONE OF THE MANY ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVES serving on the Japanese lines. During recent years the number of miles covered by electric trains has more than doubled, and nearly 700 miles of track formerly served by steam trains have now been electrified.

You can read more on

and

and

“Travelling by Train in China”

on this website.