Special Trains

Planning Emergency Railway Journeys

THE DUKE OF GLOUCESTER’S TRAIN, headed by two “AB” class locomotives at Panmure Station in New Zealand. The photograph was taken during the Duke of Gloucester’s 1934-

THE development of the motor-

Directly the application is received for the running of a special train, the divisional superintendents and any other railway companies concerned are advised by letter, telephone, or telegram, according to the time available.

The responsibility for all the arrangements falls upon the divisional superintendent in whose division the train is to begin its journey. His train section arranges, in conjunction with the train sections of the other divisions of that railway or with the other companies over the lines of which the train is to proceed, the schedule to which the special train must run, leaving and arriving at times as near as possible to the times desired. The rolling-

The station-

The staff at stations and signal boxes along the line of route are advised by printed or typewritten notice, by telegram or telephone, and the district inspectors are also notified, in the event of any signal boxes having to be opened specially for the passage of the train.

If time permits, each divisional superintendent concerned issues a notice showing the times of the special train through his division, but the divisional superintendent at the starting-

As far as possible every effort is made to avoid any disturbance of the ordinary services, and, when due notice is given, a definite path can invariably be arranged which will reduce any dislocation to a minimum. When, however, there is no time to lay down a proper path, special instructions are issued to ensure that the train obtains a good run. The special train ranks as an express passenger train, taking precedence over trains of less important nature, such as local passenger trains and goods trains.

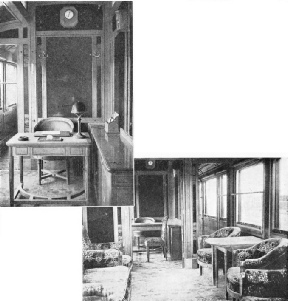

THE FRENCH PRESIDENT’S COACH. Here is the comfortable study where the President is able to continue his work during a long railway journey. Below is another view of the Presidential car. The particularly large windows are an outstanding feature of this special coach. The photograph shows the lounge, which opens into the private study.

Locomotives and coaching stock are not kept prepared in the event of emergency, but it can be safely said that at the principal termini and important junctions these can be obtained at very short notice. At the principal stations a special train can be hired and be ready within a few hours of the application for it.

As well as the ordinary fares and the charges for special vehicles, such as saloons, the following special charges are made: ten shillings a mile tor a single journey; fifteen shillings a mile on the single mileage for a double journey, provided the return journey is made on the same or the following day. The minimum special charge is £6.

A special train that was engaged for the Duke of Cambridge and a large party in the ‘eighties can be taken as a typical example of the manner in which a special train can be worked without dislocating other traffic. This special left Euston at 10.5 am, in between the 10 o’clock Scottish express (predecessor of the “Royal Scot”) and the 10.10 Liverpool express, and ran to Crewe without being once stopped by signals. This achievement meant that the signalmen were working promptly and that the drivers of the three trains were keeping time to the minute along 158 miles of road. Such close working is, however, a commonplace of ordinary express traffic. Four express trains leave Euston daily between 5.50 and 6.10 pm.

In recent years one of the most notable special trains was that provided for the Duke and Duchess of Kent for their journey from Paddington to Birmingham on November 29, 1934, on the first stage their honeymoon. This specially-

Hirers of special trains are generally in a hurry, although this is not always so. For example, recently a special train was hired to take an invalid fro Exeter to Dover, via Guildford, as this method of transport ensured more comfort and safety than any other means of travel. Nurses and medical attendants accompanied the train, and every care was taken to eliminate jolting. At Dover the invalid was taken across the Channel to France, and he travelled in a special saloon to the Riviera.

Special trains have been hired to convey dying persons who have wished to spend their last hours in their homes, and the railways have enabled that wish to be fulfilled.

Sick persons generally travel, however, in specially equipped coaches, which are attached to ordinary trains The patients are brought by motor-

The hospital trains of war time were, of course, special trains, as were the troop trains, but they were operated under abnormal conditions, and are referred to in the chapter “Special Passenger Traffic”.

Even now the railways are sometimes called upon to run special trains to enable doctors, nurses, and medical and surgical supplies to be taken speedily to the scene of an industrial disaster, when the hospitals and medical services of the area in which the disaster has occurred are unable to cope immediately with the number of injured.

Special trains have played an important part in the development of the railways. The chapter on the Santa Fe “Chief” tells the story of how this famous American train developed out of a special train ordered by Walter Scott, a wealthy miner.

In Great Britain special trains exploited the possibilities of high speed travel in the early days. One of the most famous of these trains ran on January 7, 1862, conveying a Queen’s Messenger with important dispatches. The dispatches concerned what is known as the “Trent Affair”. During the American Civil War a US warship stopped the British ship Trent and removed some passengers. There was no Atlantic cable, and therefore every effort was made to expedite the journey of the Queen’s Messenger. The Cunard Liner Europa landed him at Cork at 11.15 pm on January 6, and a special train took him to Dublin, which was reached at 3.30 am the next morning. Reaching Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire) at 4.5 am, the Queen’s Messenger embarked in a steamer and crossed to Holyhead, where a special train had been ready for two days. It consisted of three four-

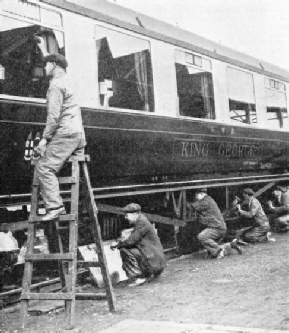

FOR THE HONEYMOON of the Duke and Duchess of Kent. Men at the Great Western Railway’s works at Swindon are here seen preparing the train in which the Duke and Duchess travelled on the first stage of their honeymoon after their wedding in 1934. The train was drawn by a “King” locomotive.

At Stafford the engine was replaced in a minute and a half by No. 372, one of McConnell’s “Bloomer” class. The run of 133½ miles to Euston was made without a stop in two hours nineteen and a half minutes, at an average speed of 57.4 miles an hour. At Tring the driver found he had thirty-

As early as November, 1830, George Stephenson’s engine, the “Planet” worked a special train to carry voters from Manchester to Liverpool for an election. The journey was performed in an hour, including a stop of two minutes for water. A delay in starting rendered it necessary for the train to use “extraordinary dispatch” to get the voters to Liverpool in time.

In the ‘forties special trains were already showing the public what the railways could do. In 1842, a special train conveying Queen Adelaide covered the seventy-

At this period, chartering a special train was very common. Frequently a business man who had missed a train on his way to an important engagement would order a special to overtake it.

It appears to have been possible for a man who had missed the train from London to Brighton to charter a special which would catch up with the ordinary train before the latter had reached halfway, provided that the special started not later than half an hour after the ordinary train. It is said that the Secretary of the London and Greenwich Railway, having missed a train, started in pursuit on an engine, which ran into the train with such violence that the legs of one or two passengers were broken.

In connexion with special trains, and the speeding up of travel, Sir James Allport was the outstanding figure. Sir James, who was knighted in 1884 for his work, joined the Birmingham and Derby Railway Company in 1839. The line, which was forty-

The occasion was when George Hudson, the “Railway King”, was elected MP for Sunderland in 1845, and was at the height of his powers. The returns of the voting were collected from the polling booths and handed to Allport, who rushed his manuscript to a London newspaper. The election result and a leading article were printed in the newspaper, and Allport was back in Sunderland with the newspaper before the announcement of the poll.

On February 26, 1848, Sir James, at the request of Messrs W. H. Smith & Son, sent a special train, with newspapers containing a report of the Budget speech, from London to Newcastle in nine hours and seven minutes, the train attaining a speed of fifty miles an hour over the circuitous route of those days.

An Unusual Lawsuit

Sir James was justly proud of the part he had played in increasing speed and comfort. When he was knighted he said he was particularly satisfied with the boon the Midland Railway Company, of which he was General Manager for many years, had conferred on third-

“When the poor man travels” he said, “he has not only to pay his fare, but to sink his capital, for his time is his capital; and if he now consumes only five hours instead of ten in making a journey, he has saved five hours of time for useful labour -

The Midland permitted the third-

One special train was the cause of a lawsuit. The trouble occurred at a period when the Great Western trains stopped for ten minutes at Swindon to allow passengers to visit the refreshment room, which was not then owned by the railway. Those passengers who did not require refreshments used to protest at the delay, and sometimes, when these passengers made a fuss, the train was started before the ten minutes were up, and other passengers were left behind.

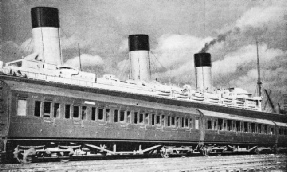

AN OCEAN LINER EXPRESS. The Southern Railway operates special expresses to its docks at Southampton, the premier port in Great Britain for long-

In August, 1891, a man travelled first-

He went to Bristol, and at Bristol took a special train, which arrived at Teignmouth at 8.20 pm. He gave the station-

The case was heard at the Brompton County Court. The judge decided that the sending on of the train three minutes before time at Swindon was an act of wilful misconduct on the part of the station-

The judge then pointed out that it had been laid down in another case that it would be unreasonable to allow a passenger, delayed in his journey, to put the company to an expense to which he would not put himself if he had no company to look to. If the passenger’s journey had been the performance of some public or private business or duty which would not admit of delay, the judge considered that the expense of a special train could be incurred. On the other hand, he was not prepared to say that joining one’s family and friends some three hours sooner -

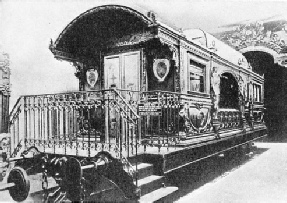

RlCHLY ORNAMENTED. The Pope’s private railway coach, which was specially appointed for His Holiness. In the days of the Papal States the Pope gave audiences at wayside stations.

The passenger was also entitled to damages for discomfort, annoyance and inconvenience. The judge cited a previous ruling when a judge had held that detention for two hours in winter, on a cold platform, with a refreshment stall containing nothing but jam tarts and bottles of soda-

Stealing a March

Archibald Forbes, a famous journalist in his day, used a special train to pull off a “scoop”. In 1874, the emigrant ship Cospatrick, with more than 400 passengers, was burnt at sea. Two boats got clear, but one foundered. The other, containing thirty passengers, drifted; but, when it was picked up by the British Sceptre, homeward bound from Calcutta, only five persons remained alive, and two of these soon died. The other three were put ashore at St. Helena, and afterwards embarked for England in the steamship Nyanza. Forbes chartered a boat, boarded the steamer at the mouth of the Channel, and persuaded the second mate of the Cospatrick to go with him to Plymouth, whence a special train rushed him up to London with the account of the disaster.

The very speedy special train run in June, 1927, by the Pennsylvania Railroad from Washington to New York after the return of Colonel Lindbergh from his transatlantic flight is referred to in the chapter “Locomotive Speed Records”, which begins on page 529. Other noteworthy special trains receive attention in the chapter “Special Passenger Traffic”, to which reference has already been made.

Many years ago, when the motor car was still in its infancy, the “regular special” train was not unknown. This apparent contradiction needs a word of explanation. A wealthy business man living in the Home Counties would place a standing order with a railway company for a special train to take him daily to and from the City.

Such a train could have been seen at the beginning of this century travelling on the Aylesbury Extension of the Metropolitan Railway -

The efficiency of the railways has reduced the demand for special trains. His Majesty the King normally travels by special train, as explained in the chapter “Royal Trains”; but other members of the Royal family often travel as ordinary first-

You can read more on

and

on this website.