The Railway Systems of Two Progressive Countries

RAILWAYS OF EUROPE - 4

MODERN EXPRESS LOCOMOTIVE built by the Borsig Locomotive Werke, Hennigsdorf-Osthavelland, near Berlin. The streamlining plates cover both the locomotive and the tender. This locomotive has the 4-6-4 wheel arrangement and there are three cylinders. The engine is designed to attain a speed of over 108 miles an hour.

THE great railway system of Germany deserves special attention as an example of up-to-date and efficient management. The Dutch railways may be considered at the same time, since not only are they closely associated with the German railways, but they also provide the chief direct communication between England and the cities of northern Germany.

Until 1932 the German railway authorities were not particularly concerned with speed, and few really fast trains were scheduled in their timetables. Since then there have been some remarkable accelerations. The high-speed mileage is largely due to the “Flying Hamburger” and other Diesel rail-cars; but there are now some very fast steam-hauled trains as well.

The first public steam railway in Germany was opened between Nuremberg and Fürth, in Bavaria, on December 7, 1835. It was a small line, serving what would be the purpose of a tramway or bus route nowadays. Its terminus at Nuremberg, though small, was quite an ambitious building with an all-over roof, and its solitary locomotive, built by R. Stephenson in England, was a small edition of the Stephenson passenger engine “Patentee” on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The engine was brightly painted green and Indian red, with much polished brass-work, and the carriages were yellow and red. The little train created an enormous impression on its first journey. Tall hats were thrown into the air, crinoline skirts swept about, and horsemen swore at their frightened, plunging steeds. That was the beginning of railways in Germany.

The German railways expanded to meet one another from widely isolated beginnings, just as the railways did in Britain. By 1890 there were approximately 27,000 miles of railway in Germany, as against 20,073 in the whole of the British Isles. In 1934 the German railway mileage was about 36,430, while that of Great Britain alone (but including the Irish lines of the LMS) was 20,251. The densest parts of the German railway system are round Berlin, with its four million inhabitants, and in the thickly populated districts of the Rhineland, the Ruhr, Saxony, and Silesia. Before the War the majority of the German main lines were owned and operated by various State administrations; thus there were the Royal and Imperial Prussian State Railways, the Royal Bavarian State Railways, the Royal Württemberg State Railways, and the Royal Saxon State Railways - Prussia, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Saxony all being constituent kingdoms of the German Empire. Then there were the Baden State Railways, the Alsace-Lorraine State Railways (now ceded to France), the Oldenburg State Railways, and several others. After the War a vast new railway administration, the German State Railway Company, was formed for the whole country. At the present time the German State Railway, or the Reichsbahn, as it is generally and officially known, works all the main lines of the country except that of the Lübeck-Büchen Railway Company, and nearly all the secondary lines in addition.

As in Great Britain, the railway system depends on certain very important centres, from which lines radiate in every direction. Naturally Berlin is the chief of these. Situated in what might be called the “Middle North” of Germany, it throws out steel tentacles north-east to Stettin; north to Rostock (for Denmark and Sweden); north-west to Hamburg, Bremen, and Kiel (for Denmark); west to Hanover and the Rhineland; south to Leipzig, Munich and Dresden; south-east to Breslau; and east to East Prussia (across the Polish Corridor), Poland, and Russia.

The Reichsbahn is a colossal concern. It operates nearly 33,400 miles of route, and is worked by approximately 23,500 locomotives and 741,500 carriages and wagons, not including the newly introduced passenger and goods rail-car stock. By the end of 1933 no less than 1,181 route miles of the Reichsbahn were operated by electric traction. By far the widest extensions of electric working have been made in Bavaria and on the through Bavarian-Württemberg main line from Munich to Stuttgart. Of the six main lines radiating from Munich, four are now electrically operated, and electric working on them extends to Salzburg, Mittenwald (and via the Austrian Federal Railways to Innsbruck), Stuttgart, and Regensburg. The remaining two main lines, to Nuremberg via Ingolstadt and to Kempten and Lindau, carry a lighter traffic than the others, and they alone are worked solely by steam.

Electric Trains

After the extensive Bavarian electric system, which derives its energy from the vast reserves of water power in the Bavarian Alps, comes the electrified area in Silesia, serving Görlitz, Hirschberg, and Breslau. The Magdeburg-Halle-Leipzig line also is electrically worked, and it was here, in central Germany, that the experimental electric main line between Bitterfeld and Dessau was inaugurated in 1911. The pioneer electric express locomotives of that line were of the 4-4-2 type, with coupled axles, like a steam locomotive. A modern electric express locomotive of the Reichsbahn, with three driving axles - not a very big type as they go - develops as much as 2,950 hp. The power output of the larger mixed traffic, heavy passenger, and freight locomotives is, of course, greatly in excess of this. In the more modern locomotives the side-rods have disappeared, and nose-suspended motors are coming into popularity. It might be said that the “locomotive” is becoming less and less like an “engine”.

The Lübeck-Büchen Railway is the only company of first-class importance apart from the Reichsbahn. It owns only about a hundred miles of line; but, with its main line from Hamburg to Lübeck, it provides a vital link between western and northern Europe, as it is used by the through sleeping-car expresses from Hamburg to Sweden and Norway via the Sassnitz-Trälleborg train ferry. The hedged meadow-land and pasture country of the route, which is very like the country between London and Rugby, was the home of the Angles who came to Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries. The Lübeck-Büchen Railway has seventy locomotives, 286 carriages, and 1,194 wagons, generally similar to those belonging to the old Prussian State administration in the pre-war days. Quite recently, however, it has introduced a service of high-speed steam rail-cars between Hamburg and Lübeck. Small as it is, Germany’s only privately-owned main line railway is excellently organized.

AN EARLY GERMAN ENGINE. This locomotive, designed by August Borsig, was one of the first to be built in Germany.

Berlin is well served in the matter of railway stations. The City Railway provides a “Belt” line similar to the “Ceinture” of Paris; but Berlin possesses something not yet found in either London or in Paris. This is a main line running right through the middle of the city, with a big through central station. This is the famous Friedrichstrasse Station, well known to all international travellers. To visualize such a station in London it would be necessary, for example, to imagine the LNER at Liverpool Street connected with the Southern at Victoria, with a great through station somewhere along the Strand. Our only parallel in Great Britain, perhaps, is the LNER line running through the middle of Edinburgh, with the Waverley Station set at its most important point. There are, of course, various terminal stations in Berlin as well. These include the Potsdamer Station, the Anhalter Station (for Munich and the south), the Stettiner Station, and the Lehrter Station. The last named serves the Hamburg line, with its excellent service of express trains, including the Diesel-driven “Flying Hamburger”. There is also a network of underground and elevated railways.

Cologne may be said to form a nearer parallel to Edinburgh, for here again is a great through station in the middle of the city, and the conditions are more similar to those prevailing in the Scottish capital. The Central Station at Cologne is the first big German railway centre to be seen by many British travellers; for through it there pass numerous international trains from Ostend and Brussels to both north and south Germany, as well as the English boat trains from Flushing and the Hook of Holland to South Germany and Switzerland.

The first British military train to enter Cologne after the war was hauled by two old locomotives belonging to the Great Western and the Caledonian Railways respectively.

Cologne is always busy. It is thronged with people soon after five o’clock in the morning, when the Budapest-Ostend Express stops there. At midnight two important express trains may be seen standing on either side of one of the island platforms, both destined for Munich, but heading in opposite directions. The one train, heading westwards, will run down the left bank of the Rhine, past Coblence, to Mainz, whence it crosses the Rhine and passes on to Munich through Frankfurt and Würzburg.

Germany’s Largest Station

The other, which has come from Flushing, and which carries the English passengers from London, York, and the North of England via Harwich, crosses the Rhine by the fine Hohenzollern Bridge, and runs down its right bank through Nieder-lahnstein. This crosses the route of the other, in scissors fashion, and strikes down through Mannheim, finally reaching the Bavarian capital by way of the electrified main line from Stuttgart. The day traveller passing through the valley of the Rhine can watch for hours the trains passing and repassing on the other side of the river. On occasion the trains appear to be racing one another. There is a strange magnificence, too, about the wide, coffee-coloured river sweeping between its hilly, castle-crowned shores. At least one ancient robber’s tower has had its interior converted for railway purposes, and the railway is made to harmonize with its surroundings as far as possible.

Karlsruhe, in the south, is an important provincial centre. It is the exchange station for the international traffic from France via the Alsace-Lorraine Railways, and the junction for lines to Basle, and to Stuttgart and Munich.

A FAMOUS TRAIN. The “Rheingold Express” in the main station at Cologne. The express consists exclusively of first- and second-class Pullmans, and operates between the Hook of Holland, Basle, and Zurich.

Leipzig is perhaps the most important railway centre in the German midlands. It has the largest station, not only in Ger-many but also in Northern Europe. It contains twenty-six platform faces in one long series, all abutting on to a large concourse. Architecturally, the. station is magnificent, and the building rivals the Union Station at Washington and the new station at Milan as being among the finest railway terminals in the world. German stations, so far as the big cities are concerned, are one of the strongest points of the country’s railway system. Even the very old stations, such as the big Central Station at Munich, are well laid out, with plenty of space for movement, and a remarkable freedom from the bottleneck formation in the approach tracks outside.

The more modern stations in Germany have high platforms, similar to those of English stations; but at the older stations the low platforms recalling French practice are in evidence. As a result, the traveller may board a train at Munich, having to climb quite a long way up into his carriage, yet on leaving it, say, at Frankfurt-on-Main, he merely steps out on to the high platform. A queer effect of this is that the train seems to have grown much smaller during the journey.

Railway travelling in Germany is a queer mixture of the comfortable and the uncomfortable. The carriages are slightly wider than those in Britain, and they are kept very clean. On the other hand, a third-class passenger, even on, say, the Berlin-Munich express, will never sit so comfortably as he would in an ordinary stopping train between London and Brighton. The majority of the third-class carriages have plain, wooden seats, painted yellow, grained, and varnished. They are quite well shaped, and more comfortable than might be supposed even on a comparatively long journey. A start has been made, however, with the fitting of upholstered seats to all main-line third-class rolling-stock, and these represent a very marked improvement.

The most comfortable third-class carriages in Germany are often considered to be those found on the Hamburg-Copenhagen express trains; but these belong to the Danish State Railways.

There was once a fourth class in Germany, and in Bavaria the fourth-class carriages were quite as good as the thirds, except that they were much more crowded. Elsewhere, however, they were rather uncomfortable vehicles, with only a limited seating capacity; the seats themselves were both narrow and angular.

First-Class “Seconds”

German second-class carriages are very comfortable, and little, if at all, inferior to the German firsts. Each compartment of an ordinary second-class side-corridor coach seats three people a side, and has arm and head rests, and adjustable seats. The entrances are at the ends of the coach, as in the latest LMS and LNER corridor stock. Each compartment has a single large window, and is fitted with folding tables. The compartment coaches without corridors, used on stopping trains over medium distances, are usually provided with clerestory roofs, which mitigate the effect of their otherwise distinctly bare interiors. In South Germany, however, the central corridor type of coach with a plain curved roof is used on the ordinary stopping trains.

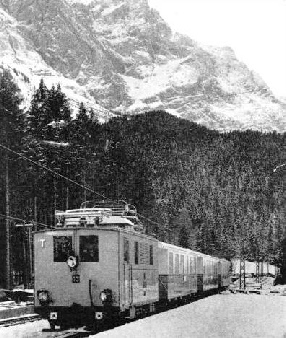

THE BAVARIAN ZUGSPITZE RAILWAY has one of its termini on the peak of the highest mountain in Germany. The railway, opened in 1931, is eleven and a half miles in length, and is divided into adhesion, rack-and-pinion, and overhead cable sections.

The dining and sleeping-car services over the Reichsbahn, apart from a few belonging to the International Sleeping Car Company, are operated by the Mitropa Company, which has its headquarters in Berlin. “Mitropa”, by the way, is a corruption of Mitteleuropa, the German for Central Europe, for the full imposing title of the concern is Mitteleuropäische Speisewagen und, Schlafwagen Aktien Gesellschaft. The Mitropa cars are similar to those of the International Sleeping Car Company; that is to say, the sleeping cars accommodate three passengers per compartment in the third-class, two in the second, and one in the first. As the three third-class berths are placed one above the other, the compartments are rather cramped. The berth itself is harder than that of a British third-class sleeper, and there is, of course, much less headroom; but spotlessly clean bedclothes are invariably provided. The second- and first-class sleepers are exceedingly comfortable. The exteriors of the cars are painted “Midland” red, with bold gilt lettering. Of the restaurant cars, little need be said, save that they provide the passengers with good and plentiful food. But the finest train of the Mitropa Company is the “Rheingold Express”, which consists entirely of first- and second-class Pullman-type coaches, running between the Hook of Holland, Basle, and Zurich. The “Rheingold” is among the handsomest and most comfortable trains on the Continent, rivalling even the day section of the “Sud Express” which runs between Paris and the Spanish frontier at Irun. The exteriors of the coaches are painted a rich violet, with cream coloured upper panels, and, as German express locomotives are painted a glistening ebony black, with scarlet wheels, the train has a really striking appearance. Nor does it lose this after it has crossed the Dutch frontier, for the Netherlands engines are painted bright apple green, and have highly polished brass domes.

Taking an average standard, German locomotives are larger than British, and rather more powerful. The heaviest steam passenger trains are entrusted to very big “Pacific” type engines, some with two, some with three, and some with four cylinders. In Bavaria, and on the “Rheingold” and certain other trains, a lighter type of 4-6-2 locomotive is employed. These are four-cylinder compounds of a class originally designed by the great Munich firm of J. A. Maffei for the Bavarian State Railways. They are considered the handsomest engines in Germany, though the ideal on the Continent is different from that popular with British locomotive men.

That they are good engines, too, is shown by the fact that their design, with various minor modifications and improve-ments, has been perpetuated during a period of nearly twenty-five years. A few years ago a 2-8-2 passenger type was inaugurated for the operation of very heavy trains running to medium schedules. This was an interesting anticipation of the LNER introduction of the “Cock o’ the North” class on its Scottish main lines. Before the war of 1914-1918, eight-coupled express engines were practically unknown. The commonest type of steam locomotive in Germany, however, is the 4-6-0. They are everywhere, and may be seen working anything from a Berlin-Paris express to a leisurely local among the meadows of Lower Franconia. The general design originated with the “P 8” class on the old Royal and Imperial Prussian State Railways before the war. These, together with a new standard 2-6-0 class, work all the longer-distance slow trains. With the coming of these new standard “Moguls”, the last German 4-4-0 locomotives have finally passed out of active service. In Germany to-day, the 4-4-0 locomotive is as out of date as the 4-2-2 in England. It must be pointed out, of course, that Germany has never built any modern four-coupled express engines, such as the “Shires” of the LNER and the “Schools” of the Southern Railway. Before the war many German locomotives bore names, usually those of places which they served, but the fine brass name-plates disappeared when metal was at a premium.

SCIENTIFIC PROGRESS on the railways exemplified by the above picture, which shows one of the experimental air-propelled types of rail-car tried out in Germany. This rail-car was built to achieve a speed of over ninety miles an hour.

The Diesel-operated rail-car which runs between Berlin and Hamburg, was, until May, 1935, the fastest train in the world. Some of the steam-hauled trains on the same route have very fast bookings, though these are naturally below the schedule of the rail-cars. Moreover, the steam-train services on many other lines, notably that between Berlin and Hanover, are excellent. Certain trains are booked, start to stop, at speeds of sixty miles an hour and over. Besides the “Flying Hamburger”, other very fast rail-car services were planned to operate in the spring of 1935. Some of these have start-to-stop schedules of over eighty miles an hour.

There is in Germany a system of train classification which is unknown in Great Britain. The fastest trains do not take third-class passengers, and a substantial supplement is charged for travelling on them. Then come the ordinary express trains, carrying first, second, and third class, for which a smaller supplement is charged.

In the next category are fast trains with second and third class only, for which there is a still smaller supplement. Finally, there are the ordinary passenger trains, carrying second and third class and stopping incessantly, on which no extra charge is made. The express rail-cars carrying second class only, are exceptional.

A NETHERLANDS RAILWAYS LOCOMOTIVE. This engine, No. 929, was built by Beyer, Peacock & Co, at Manchester, in 1874. Many of the older Dutch locomotives came from this firm. Some of these old British-built locomotives are still in use.

The present Netherlands Railways Company operates all the main lines in Holland which were formerly owned and worked by the Dutch State Railways, the Netherlands Central Railway, the North Brabant Railway, and the excellent little Holland Railway. On entering Holland from Germany the traveller finds an English atmosphere about the railway system. True, the stations resemble those of the German lines, and so do the passenger coaches, though ordinary compartment carriages predominate; but the locomotives have the neat appearance and attractive painting which is associated with British systems.

For many years the Dutch State Railways had practically all their engines built at Manchester by Beyer, Peacock and Company. Examples of this firm’s work are to be seen everywhere, varying from modern 4-6-0 express locomotives to queer old 2-4-0’s at work in some station yard. The latest Dutch locomotives are built in Holland; but they retain the neat outlines of their predecessors, and most passenger engines have beautiful brass domes, such as have not been seen in England since the War. Four-cylinder 4-6-0’s are standardized for express passenger traffic, while in the coalmining districts of Limburg there are huge 4-8-4 tank engines of recent construction.

The Netherlands Railways operate 2,105 miles of line, covering the whole of the country, and linked up by a network of road motor routes and, queer as it sounds, cross-country tramways. The last named are worked by steam or electricity, the latter motive power gaining ground steadily, though one still finds steam tramways everywhere. On the railways proper there are two important lines operated by electric traction. The first of these is the main line from Amsterdam to Rotterdam and Dordrecht via Haarlem and The Hague. This is part of the old main line of the former Holland Railway. The other is a separate line from Rotterdam to the Hague and on to the seaside resort of Scheveningen. The electric trains consist of motor and trailer corridor coaches, as on the London-Brighton line; and on the Amsterdam-Rotterdam expresses first-, second-, and third-class accommodation is provided. A half-hourly electric service is maintained between the two cities. At Amsterdam the electric trains use the Central Station, which rivals the stations of Germany. At one place along the route it is possible to see the railway, a canal, a rural tramway, an arterial road, and a track for cyclists all running parallel to one another. Moreover, they are all following the seashore.

Recently the Netherlands Railways, faced with severe road competition, have been popularizing express rail-cars for fast inter-city traffic. Unlike the German cars, they take third-class passengers. Speeds in Holland are relatively low on the whole; but very fast running is out of the question, on account of the numerous permanent way and other slacks encountered.

THE CENTRAL STATION AT AMSTERDAM. The Netherlands Railways Company, formed in 1917, has electrified lines between Dordrecht, The Hague, Rotterdam, Scheveningen, and Amsterdam. The first railway line in Holland ran between Amsterdam and Haarlem, and was opened in 1839.

You can read more on

“Electrification in Europe”,

“Some German Achievements” and

“Speed Trains of Europe”

on this website.