Railroads of Norway

Bold engineering in the land of the midnight sun

ALONGSIDE A FJORD on the journey from Bergen to Oslo. The first sixty-

IT is by way of Bergen that the most dramatic approach is made to Norway. To the tourist travelling across the North Sea from Newcastle-

Bergen might be termed the “Clapham Junction” of the coastal shipping routes of Norway. Owing to the extraordinary configuration of this country -

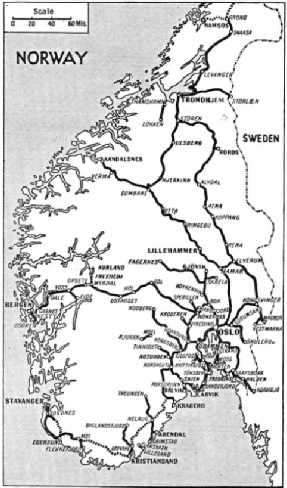

Apart from the capital city of Oslo, in Eastern Norway, the country possesses three towns sufficiently large to be called cities. From north to south they are Trondhjem, Bergen, and Stavanger. Trondhjem was the first to be connected with Oslo by rail, and this route gave the least difficulty, from the engineering point of view. Bergen came next, though in this instance the difficulties were so great that railway communication was not completed until 1909. Stavanger has not yet been linked up. South-

Work is in progress, at the time of writing, on the Sörland Railway, which will first link up the Kragero line with the large town of Kristiansand, in the extreme south of Norway, and will then be extended further westwards to join the Stavanger-

Until the Sörland Railway is open, however, the line connecting Bergen with Oslo easily holds the supremacy in Norway, both for scenic attraction and for its engineering achievements. As far back as 1874 the first section of the line was opened, penetrating inwards from the coast as far as Vossevangen, or Voss, as it is known for short, sixty-

As far as Voss the railway is carried for the most part along the shores of Sorfjord and a branch of this lengthy waterway known as Bolstadfjord. On a ledge blasted out from the precipitous fjord-

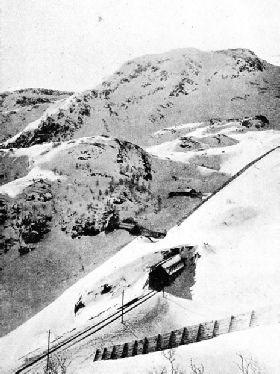

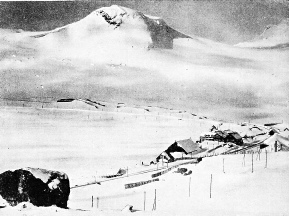

PROTECTION FROM SNOW on the Bergen-

At Voss the railway lies midway between two of the best known fjords in Norway -

On leaving Voss by the main line, we find that steep climbing begins at once. Eight-

Herein lay one of the two principal engineering difficulties. In Switzerland the average snow-

A very short time after leaving Voss the railway is well above the tree-

As the line mounts higher and higher, snowsheds begin to appear. The traveller who desires to take in every detail of this wonderful journey grows progressively more resentful as snow-

A SNOW CUTTING is being threaded by an express on the Oslo-

Toiling upwards, we find the long rampart of the Urhovde Mountains athwart the track, and just beyond Upsete Station there is seen the entrance to the great Gravehals Tunnel. Longest of all the tunnels in Norway, it is 17,413 ft -

Furthermore, this was but one of 183 tunnels on the route. In carrying out the work, another formidable difficulty was the fact that no roads existed through this wild country.

Owing to the climate, there were only three months in each year during which work could proceed in the open, and in some years, such as 1899, when Taugevatn Lake, at the summit of the line, was still solidly frozen by the middle of August, even shorter periods. In the tunnels work continued day and night throughout the winter, and the tunnel workers had to live a life of isolation for seven or eight months at a stretch. Their greatest difficulty in midwinter was that of evacuating the broken rock from the tunnels as it was blasted away. The tunnel mouths were completely closed by great drifts, there were small holes through which the men had to crawl in and out.

At the height of the season as many as two thousand men were at work at once, sometimes for as long as fifteen hours at a stretch in the nightless days of the Norwegian summer, of which the best possible advantage had to be taken.

From Voss, in the west, across the mountains to Haugastol, to the east, the paymaster, accompanied by a mountain guide, made the journey monthly on skis to pay the workers in their remote encampments. It was a hazardous journey in the winter. Early in 1905 a blizzard overtook the two men, and it was not until six months later, in July, that the bodies were recovered from the crevasse into which they had fallen. During the 1902-

FROM COAST TO COAST the railway network penetrates the mountain barriers. The broken lines indicate routes still under construction.

In the summer of 1906 the formation of the line was in a sufficiently forward state for track-

Immediately the train leaves Gravehals Tunnel, and emerges at Myrdal, the traveller faces one of those dramatic scenic sensations which are not revealed to those who merely content themselves with a coastal cruise of Norway. Looking to the south he sees a valley, of no exceptional characteristics, sloping down amid bare mountains to the line.

Through the opposite window of his coach, to the north, he sees the same valley dropping sheer for some 1,600 ft into the chasm of the Flaamsdalskleiva.

Up from its depths there comes the famous zigzag road, with its twenty-

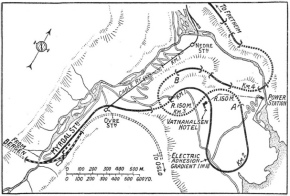

A marvel of railway location work is now being carried out down the Flaamsdal. For Myrdal and Fretheim, despite their difference in level of nearly 3,000 ft, are being connected by railway. The first stage of the descent is illustrated in the reproduced plan, and must be one of the most extraordinary railway spirals. Tunnelling is freely employed, with a gradient of 1 in 18, as there are only sixteen miles available to complete the descent. Electric power will be used for working.

A MARVEL OF RAILWAY ENGINEERING. The extraordinary spiralling necessary to overcome the gradient between Myrdal and Fretheim -

Directly after leaving Myrdal, the main railway line to Oslo, for a short distance passing between a succession of tunnels, almost overhangs the profound depth of the Flaamsdal. Then it turns inland, and presently, as it skirts Taugevatn Lake, the summit level of 4,270 ft is reached. Along this stretch it is only in the late summer that the immediate surroundings of the line are free from snow. Snow-

The highest station of importance on the line, which is next reached, is Finse, 4,007 ft above sea-

Falling gradients now lie ahead for a long distance. At Haugastol, 3,240 ft above the sea and seventeen miles farther on, we find ourselves in the middle of the great Hardangervidda, or, more literally, Hardanger “void” or “desert” -

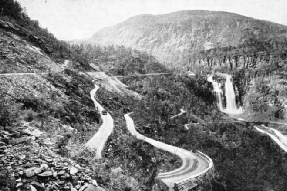

THE WAY TO THE STATION. An astonishing zigzag road carries the traveller out of the Flaam Valley to the railway station at Myrdall, on the Bergen-

Still descending, the railway reaches the first signs of cultivation at Gjeilo, and presently the train arrives at Aal, in the fertile valley known as Hallingdal. Here the line is 164 miles from Bergen, and the level has dropped to 1,432 ft. Aal is an important locomotive depot, being roughly at the midway point on the line, and engines are changed there. Beyond Aal the engineer-

The remainder of the route lies through the forest lands of Norway, which cover one-

There is another Norwegian railway which has a good deal to commend it from the standpoint of engineering interest, known as the Rauma Railway, lying considerably to the north of the capital. It branches at Dombaas from the main line from Oslo to Trondhjem, and was not opened until 1923. Even the section of the main line from Dombaas on to Trondhjem dates back only to comparatively recent years. Prior to its opening, the route to Trondhjem was farther to the east, by a metre-

THE NEW LINE from Voss to Eide is shown on the extreme left in this photograph. The track runs beside the road, which is sharply zigzagged, and affords magnificent views of the lovely Skjervet Waterfall, seen to the right on the middle distance.

Before the war the decision had been reached to lay a branch from this line, leaving it at Dombaas, down the Rauma Valley to the sea at Aandalsnes. Apart from its value in opening up a district of exceptional scenic attraction to the tourist, an important idea behind its construction was that of affording better access to the capital from the fishing grounds round the large coastal town of Aalesund.

Gradients of 1 in 50

The distance from Dombaas to Aandalsnes is only seventy-

IN WINTER DRESS. The highest station of importance on the main east-

Soon, from the carriage window, across the valley and at a level lower by some 450 ft, the traveller sees what appears to be another line. Before very long his own train will be passing over it. The engineers have here followed their customary expedient, when considerable differences in altitude have to be negotiated in a short distance, without any steepening of the ruling grade; they have doubled the railway back on itself in a gigantic S-

The train turns to the left into Stavem Tunnel, which has been bored in semi-

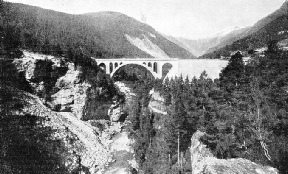

This is made by means of the magnificent Kylling Bridge, built in masonry with a span of 146 ft, and carrying the rails 194 ft above the torrent of the Rauma. This great structure alone cost the equivalent of £40,000. So the railway is carried across to the south side of the Rauma, now resuming its original direction of running, but 450 ft lower in altitude.

IN MOUNTAINOUS COUNTRY. Snow-

Towering above the line on the south side of the valley are the weird shapes of the Trolltinderne, or “witches’ peaks”, and guarding the entrance to the valley is the fine pyramid of the Romsdalshorn, the nearest approach in shape that Norway can produce to the more famous Matterhorn in Switzerland. So the train reaches Aandalsnes, on the Eisfjord, a holiday centre and halting-

Apart from the Sorland Railway and the railway from Myrdal to Fretheim, to which reference has already been made, the Norwegian Government is also carrying out railway construction on an extensive scale beyond Trondhjem. North of Trondhjem there is a small junction known as Hell -

Work is proceeding at the time of writing on a further extension which will carry the Nordland Railway, as it is called, still farther northwards to Bodo, a town within the Arctic Circle. Here, again, the fisheries of the Lofoten Islands -

In the Arctic Circle

Still farther to the north, and here, well within the Arctic Circle, lies the port of Narvik, with its great stone quays from which enormous quantities of iron ore are shipped to various parts of Europe. Only a small part of the railway which comes down to the coast at Narvik is within Norwegian territory; the bulk of it is in Sweden. The frontier, at Vassijaure, is 281½ miles away, and is connected with the main Swedish system. It is curious to reflect that on a line like this signal lights and engine headlamps never need to be lighted for a considerable period in the summer, and can never be extinguished for an equal period in the winter. The land of the midnight sun is also the land of the midday night, which is not quite so pleasant.

There is one other railway in Norway which deserves a passing mention. The capital of Oslo possesses its own tube railway, which begins in the heart of the city at the National Theatre station, entered by staircases from the busy Karl Johan’s Gade, the main shopping street of Oslo. From here the line tunnels under the Royal Palace and, after passing a station at Valkyrie Place, comes out into the open at Majorsteuen, which was the original terminus.

At first the Holmenkol-

In winter the whole of this ridge is deeply covered with snow, and the favourite pastime of the Oslo residents is to take their toboggans with them on the electric cars, to travel up by train to the summit, and then enjoy a glorious coast back down a specially made road into the capital again. Few, if any other, cities can boast the possession of a line which starts as a city tube and finishes as a mountain railway.

This quality of uniqueness is not confined to the Oslo tube. The railway in Norway has, as we have seen in this chapter, had to fight for existence against extraordinary odds.

KYLLING BRIDGE, on the Rauma Railway, is a beautiful masonry arch of 146 ft span. It carries the rails at a height of nearly 200 ft above the rushing waters of the Rauma River.

You can read more on

,

And

on this website.

You can read more on

in Wonders of World Engineering