Industrial Railways (2)

The Operation of Two Small but Remarkable Systems

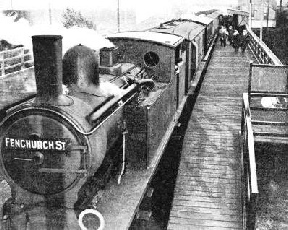

GALLIONS STATION on the Port of London Authority Railways. This system, which serves almost all the London docks, has a track mileage of nearly one hundred and forty. Apart from an immense volume of goods traffic, passenger trains are run on the railway by the LNER between Fenchurch Street and Gallions Stations.

THERE exists in England a busy railway system with nearly a hundred and forty miles of permanent way, operated almost entirely without signals, serving the needs of one of the world's greatest ports, and fulfilling an essential part in feeding the people of Great Britain. This is the little-

This system links up the main lines with the whole of the docks, except the London and St. Katharine Docks, and the Surrey Commercial Dock -

The beginnings of the Port of London are lost in the mists of antiquity, but its recorded history goes back to the days of the Roman occupation of Britain. The first dock, which still exists under the name of the Greenland Dock, was constructed in 1696, when it was known as the Howland Great Wet Dock, and now forms part of the Surrey Commercial undertaking. It was not, however, a dock in the modern sense of the term, as there were no warehouses or other accommodation for loading, unloading, or storage. Its chief purpose was to afford a safe anchorage for ships, to which end trees were planted so as to break the force of the wind. The first dock proper was the West India Dock, which was sanctioned by Parliament in 1799, and opened three years later by William Pitt, the Prime Minister at that time. Since 1909 the whole of the dock system has been vested in the Port of London Authority or PLA, a public body with a constitution resembling that of the London Passenger Transport Board. The PLA has jurisdiction over the seventy-

The largest of the docks are the “Royal” group, which are really one divided into three sections, and claimed to be the largest enclosed dock area in the world; they cover just over 1,100 acres, with a water area of 246 acres, and twelve and three-

The Authority’s railways, which are largely a heritage from the days of separate company ownership, connect the docks, sheds, and warehouses with the main railway system, thus enabling merchandise to be dispatched and received between a ship and any part of the country. Direct communication is given with the LNER and LMS Railways, while the Great Western also has access by means of running powers over the North London Section of the LMS.

The Royal Victoria Dock, although far from being the oldest, was the first to have railway facilities, and is claimed to have been the first railway-

It was built in 1855, during a period of great railway and industrial expansion throughout the country, and its owners, “with commendable prescience as to the potentialities of the new form of transport, laid down two lines over which all traffic was worked”. As happened on the Bass brewery line, horse haulage was at first employed on the dock lines. The reason was partly because the method was, in those days, considered adequate to meet traffic requirements, and partly because of a “certain timidity, or deep-

The importance of the Victoria Dock lines lay largely in the fact that they gave direct access to the Great Eastern Railway (now incorporated in the LNER) by a junction at Connaught Road. The line thence to Gallions, now known as the Royal Albert Dock Railway, which has two intermediate stations and is 1 mile 61 chains in length, is the only section of the Authority's railways on which passenger traffic is now regularly worked. LNER coaching stock is used for the purpose.

Horse Transport Displaced

When communication with the Great Eastern was first provided, the method of working was for the railway company to hand over wagons at the beginning of the dock lines, on which they were hauled by horses. This system had obvious inconveniences, and although there is no record of the exact date on which locomotives were substituted for animal traction, the Millwall Docks, which were opened in 1864, were from the outset equipped with adequate railway facilities, including locomotives for the handling of internal traffic.

The “deep-

900,000 PASSENGERS are carried annually over the lines of the Port of London Authority Railways. The system has direct communication with the LNER and LMS Railways. This illustration shows a Gallions-

900,000 PASSENGERS are carried annually over the lines of the Port of London Authority Railways. The system has direct communication with the LNER and LMS Railways. This illustration shows a Gallions-

The West India Dock Company also showed its opposition in other ways, notably when it was proposed to build the London, Blackwall and Millwall Extension Railway, which improved the position of the Millwall Dock undertaking by linking it up with the main railway system, but in the process also traversed West India Dock property. The owners of the West India Dock fought the project step by step. When the line was in 1869 opened for passenger traffic, which was at first worked by a combination of horses, endless cable, and locomotives, they “appointed a manager to look after their interests on their part of the line and to resist the steam engine”. But this attitude of obstruction could not stay progress indefinitely, and in 1880 the Board of Trade gave special sanction for the use of locomotives, which enjoyed the local nickname of “Coffee Pots”.

The Millwall line, although only a mile and a half long, was owned by three separate companies, and, before its reconstruction, had no fewer than five level crossings and three swing bridges on its short length.

The passenger service, which was worked in conjunction with one to and from Fenchurch Street, proved remunerative for many years, but the competition of motor omnibuses and other newer forms of transport subsequently caused it to be operated at a heavy loss.

After trying to bring about an increase in traffic by running steam rail motors, the Port of London Authority decided in 1926 to close the line for passenger business. But its importance for goods traffic is, of course, still considerable.

The present system, including the Royal Albert Dock Railway, which is the only section to be provided with signals, is 139 miles 61 chains in length. The Albert Dock line, although built on private property, was constructed as a statutory undertaking, and the Act of Parliament obliged the dock company to run two passenger trains a day, one in the morning to Gallions, and a second, in the evening in the reverse direction.

This modest requirement would hardly suffice to meet present-

The PLA Railway system fulfils a dual purpose. It facilitates the movement of internal traffic, and enables through traffic to be operated to and from the main lines. The Royal Albert Dock Railway exemplifies both these functions. When this dock was built, an adequate railway system was provided, together with interchange facilities with the Great Eastern Railway. Loco-

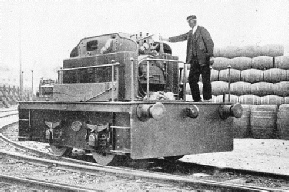

A MANUALLY-

For economic reasons this service was eventually withdrawn; the Dock Company disposed of its passenger stock, and entered into an agreement with the Great Eastern Railway under which the latter undertook to combine the running of the former separate dock railway service with its own service from Fenchurch Street and Stratford.

In addition to lessening expense, this arrangement improved the train service by obviating the necessity of changing at Custom House Station. The railway company worked the service on a train-

As already mentioned, goods traffic is worked to and from the docks by three of the four great railways. The business embraces almost every variety of foodstuffs, general merchandise, livestock, and even such exceptional consignments as railway coaches for export overseas. Over a hundred booked and special trains are dealt with daily at the Port of London, including the express goods trains from Tilbury, which carry traffic to remote destinations.

A few details of the working of these express goods trains may be of interest. Tilbury Docks have in recent years undergone considerable improvement and enlargement, and this section of the Port of London is now equipped with every facility for dealing with the largest passenger and cargo vessels.

Express goods traffic from Tilbury is, where possible, dispatched early in the day, and the trains are made up so as to serve a considerable number of destinations. A typical example of a day's work is provided by the running of three trains between 9.57 am and 3.20 pm, which between them deliver merchandise to Aberdeen, Belfast, Birmingham, Bradford, Derby, Dublin, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester, Nottingham, Sheffield, Stoke-

Although it no longer operates coaching vehicles, the Port of London Authority owns a respectable amount of working stock. The locomotive stud numbers twenty-

Wagons were introduced at an early date, at first mainly, if not entirely, for the handling of internal traffic, for which some of the present stock is still exclusively reserved. The wagon stock totals 602, of which rather less than half -

The total year’s volume of traffic varies, of course, in accordance with world trade conditions. A typical figure is that for 1934, when 1,155,685 tons of merchandise were carried over the Authority’s Railways, necessitating the use of 429,887 wagons. This works out at an average load of only about two and three-

As already stated, signalling is confined to the Royal Albert Dock Railway. When special passenger trains are worked over the other dock lines, safety of operation is secured by the observance of the Ministry of Transport regulations requiring all points to be clipped and padlocked, and flagmen to be on duty. This special passenger traffic is among the most interesting operating features of the PLA Railways. It is composed of passengers and their friends travelling to and from ocean liners and other steamers. It is worked both by the LNER between the Royal Docks and Liverpool Street and Fenchurch Street, and by the LMS between Tilbury, Fenchurch Street, and St. Pancras.

The “Boat Specials” often handle a heavy volume of traffic, and this business is also of a much more extensive nature than is usually realized, as many as 1,100 “specials” having been run in a single year. The shipping lines concerned include the Cunard-

From three to four special trains are often run in connexion with the arrival or departure of a single liner. Four trains carrying 1,034 passengers and their baggage have been dealt with in an hour and twenty-

Exceptional facilities are provided for dealing with the Peninsular and Oriental traffic. Three trains of the normal make-

Expedition characterizes also the handling of the goods traffic at Tilbury Docks. A typical instance is the loading of 120 bales of wool, necessitating the use of five wagons. Loading began at 1 pm, train left the dock at 3.20 pm, reached Brent at 7 pm after a circuitous journey round London and its environs, and arrived at its ultimate destination at Bradford, Yorkshire, within eighteen hours of the beginning of unloading. This represented no exceptional performance. The traffic is handled in such a way that, as far as possible, merchandise leaving Tilbury one day shall be handed over to the consignee early the next morning.

At first sight, it may seem curious that the Surrey Commercial Dock, which includes the first to be built in London, should, similarly to the London and St. Katharine Docks, still be un-

The Railway Department of the Port of London Authority is worked as a separate undertaking, under the management of a Railway Superintendent, whose functions are distinct from those of the Docks Superintendent. The Superintendent at the time of writing is Mr A. Phillips, who had seen service on the Great Western Railway before taking charge of the largest and most important dock railway system in the world.

It is perhaps necessary to point out that the term “private railway” is applicable to systems of widely varying natures, and that the Port of London Railway occupies a somewhat exceptional position. Although it is an undertaking situated entirely within private property, it performs the same functions as an ordinary public railway, as it carries general merchandise for others. It thus differs from such private systems as those of the Bass Brewery and of the Gas Light and Coke Company’s works at Beckton, Essex, and also from the interesting private system at the brewery of Messrs. Arthur Guinness, Son and Company, Ltd, at St. James’s Gate, Dublin. As with the Bass undertaking, the Guinness Brewery, one of the largest in the world, had already been established for many years before it was provided with railway facilities.

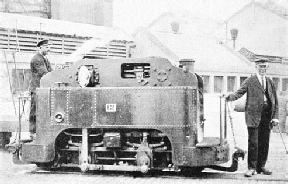

ENGINE NO. 12, one of the 0-

The system to-

The highest or “Upper Level”, on which are situated the two breweries, the fermenting rooms, and the hop and malt stores, stands some 60 ft above the quay on the banks of the Liffey. The “Middle Level” accommodates a vast malt house. The cooperage shops, cask-

Since the railway serves practically the whole of the brewery, communication between these three levels has necessitated some heavy gradients. On one section of the narrow-

NARROW-

These ten miles of line really represent two distinct systems. The narrow-

The purpose of the standard gauge lines is to interchange traffic with the main Irish railway system, the whole of which is connected with the Brewery. The broad-

Brewery Locomotives

The activities of road vehicles within the brewery limits have made it necessary to lay the narrow-

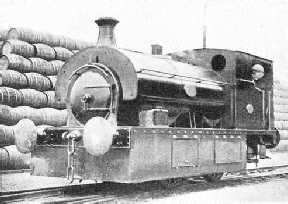

BROAD GAUGE LOCOMOTIVE No.3, built by Hudswell, Clarke & Co., Ltd., of Leeds, for the two miles of 5 ft 3 in gauge track laid within the St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. The main dimensions of this 0-

The broad-

There are nineteen locomotives, built at various dates between 1882 and 1921. The oldest was constructed by the Avonside Engine Company, Ltd, of Bristol, and the remainder at the Cork Street Foundry and Engineering Works, Dublin. It is noteworthy that local builders should have been responsible for both Guinness and Bass Brewery engines.

ON THE 1 FT 10-

The narrow-

The broad-

Although the broad-

0-

0-

You can read more on

and

and

and

on this website.