Engineering Marvels of the Lötschberg Line

RAILWAYS OF EUROPE - 15

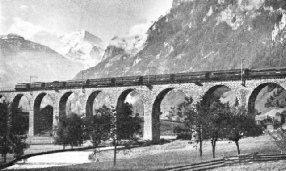

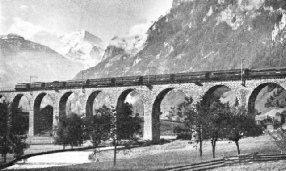

CROSSING THE KANDER. A heavy international express train leaving Frutigen for Kandersteg. In the background are the snow-mantled summits of the Balmhorn and Altels. The masonry viaduct is 90 ft above the river and 910 ft long.

AMONG Swiss main lines there are two claimants to the distinction of possessing the most spectacular route, whether judged from the engineering or from the scenic standpoint. They are the St. Gothard Railway, already described in detail in an earlier chapter, and the Lötschberg, or, to give its full title, Berne-Lötschberg-Simplon Railway.

The St. Gothard is much the longer of the two, but the Lötschberg crowds into its fifty-three miles, from Thun to Brig, an equal, if not greater, succession of sensations.

The St. Gothard Railway forms part of the Swiss Federal Railway system, but the Berne-Lötschberg-Simplon is an independent company. Early in the present century the decision was reached to construct a shorter route to Northern Italy from Berne, the capital of Switzerland, as well as from Neuchâtel, and other towns in the populous basin of the Aar. Previously a considerable detour was necessary, first to the south-west, to Lausanne, and then by the Simplon main line, which itself has to follow the deep southward bend of the Rhone Valley, to Martigny, before it can proceed north-east to Brig, at the mouth of the Simplon Tunnel. From Berne to Brig by this circuitous route was 140¾ miles - a distance which the Lötschberg project tried to halve.

There were other attractive advantages connected with the scheme. It would put the popular resort of Kandersteg on the railway. It would make the delightful holiday region of the Bernese Oberland much more accessible than before from Northern Italy. Most important of all, it would offer a new and direct through route from Paris to Northern Italy, and so stood every chance of securing a share of the lucrative international traffic as well.

Through portions of the Swiss express trains from Paris and the Channel ports were already being detached at the well-known junction of Belfort, on the main line of the Eastern Railway of France. These came direct across the Swiss frontier at Delle, and thence by way of Porrentruy, Delemont, and Bienne to Berne and Interlaken. Plans were in hand to shorten this route also by tunnelling through the main range of the Jura from Moutiers to Granges, and so still further to expedite the Paris-Berne part of the journey. This project came to fruition in 1916, when the Grenchen Tunnel, five and one-third miles long, was opened for traffic.

With these favourable prospects, therefore, the Berne-Lötschberg-Simplon Railway Company was formed by a group of French financiers, and in 1907 the work of construction began.

It was, however, only from Spiez, on the Lake of Thun, to Brig, a distance of forty-six miles, that new construction was necessary. From Thun to Spiez, Interlaken, and Bönigen (on the Lake of Brienz) there was already in existence the Bernese Alpine Railway, which was acquired by the new company, together with certain other small privately-owned lines, of which the most important was the direct line between Berne and Neuchâtel.

The plan of the promoters was to use the valley of the River Kander from Spiez up to the southern limit of the upper basin of the valley, in which lies the village of Kandersteg. Thence it was intended to tunnel for a little less than nine miles under the main ridge of the Bernese Alps, emerging into one of the deep lateral gorges which debouch from the north into the Rhone Valley. Finally the new line was to descend along the north wall of the Rhone Valley to join the Simplon main line just outside the station at Brig.

This scheme offered a remarkably direct course, in view of the mountainous country to be traversed; but great difficulties stood in the way of carrying it successfully into effect. In particular, the level of the railway on leaving Spiez would be 2,070 ft above sea level; at Kandersteg, only thirteen miles away in a direct line, it would have to be all but 4,000 ft up; and at Brig, at the farther end of the new railway, the level would be down again to 2,215 ft. Moreover, the location would be bound to strike the Rhone Valley, on entry, at an altitude far more than a thousand feet above the valley-floor, and the gradual descent to floor level would be a difficult and a costly undertaking. No such obstacles as these, however, were allowed by the promoters to deter them from their enterprise.

And now, as in the description of previous railways of similarly spectacular description, the best way in which to appreciate the engineering marvels of the route is to take an imaginary journey over it.

Powerful Electric Locomotives

The best approach is the Delle “gateway” of Switzerland, which gives so characteristic an entrance into the country, through the wooded defiles of the Jura mountains. Immediately after the Grenchen Tunnel has been threaded, the passenger may see in clear weather, sixty miles to the east across the broad plain of the Aar, the glittering ice-mantled crest of the main chain of the Bernese Alps. Through this, three hours later, the train will be making its way.

Electric locomotives of the Swiss Federal Railways haul the express from Delle to Berne, and on for another nineteen and a half miles to Thun, where the Lötschberg locomotive backs on. If this is one of the heavy international trains, one of the four enormous Sécheron locomotives will probably be attached. These remarkable machines of the 1-C-C-1 type - that is, two independent groups of three uncoupled driving axles, flanked by carrying axles at either end - are rated at 4,500 horse-power, and were designed and built at the Sécheron works in Geneva. Their 90-tons predecessors, of the 1-E-1 or 2-10-2 type, are capable, with their 2,500 horsepower rating, of handling 310-tons trains over the continuous 1 in 37 gradients between Spiez and Brig; but the newer locomotives are designed for the haulage, if necessary, of 600-tons trains without assistance. They have proved their ability, on test, by starting a 600-tons train on the 1 in 37 grade, and accelerating up the gradient to forty miles an hour with this load. The rostered daily mileage of these locomotives to and fro over the mountain section is 310.

From Thun the full glory of the Bernese Alpine chain, seen across the blue waters of the Lake of Thun, bursts on the view of the traveller. On the left are seen the Wetterhorn and the Schreckhorn, in the centre the familiar group of the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau, and on the right the shapely form of the Blümlisalp. Immediately below the Blümlisalp is the valley of the Kander, up which the railway has to pass. To the right of that, in the foreground, is the perfect cone of the Niesen, which, with its lower altitude, made accessible by a funicular railway, is the finest and most popular Alpine viewpoint in the district. On the way up to Kandersteg we shall pass the lower terminus of the Niesen line.

It is but a brief run - six and three-quarter miles - from Thun to Spiez, along the shores of the Lake of Thun, during which the train climbs about two hundred feet. The fine modern station at Spiez stands well above the lake, commanding a beautiful view of the bay, with the old castle guarding it on the left. A considerable amount of traffic is dealt with here, for Spiez is a junction of importance. The main Lötschberg line here diverges from the original line to Interlaken, and, from the south-east, coming down the narrow Simmental, there is the branch, also owned by the Lötschberg Company, from Zweisimmen. That is prolonged by the well-known narrow gauge Montreux-Oberland Bernois Railway - M.O.B. for short - which runs on through Gstaad and Chateau d’Oex to Montreux, and in summer forms the principal highway between the Bernese Oberland and the popular holiday resorts on the Lake of Geneva.

In the ordinary course many of the Lötschberg trains have their Brig and Interlaken portions combined as far as Spiez, but in the height of the summer season the traffic is so heavy that independent trains have to be run from Berne to this point. The Lötschberg train probably includes in its formation through coaches for Milan, local coaches for Brig, a Swiss restaurant car, and, if it is one of the morning trains, sleeping-cars from Calais or Boulogne to Kandersteg or Brig. Coaches of the Swiss Federal, the Lötschberg, the Italian State, and the French Northern or Eastern Railways are often included in the same train.

Coming into Spiez the train has continued beyond the end of the Hondrich-Hügel ridge, which cuts the Kander Valley off from the lake. This has first to be tunnelled under, by a bore a mile in length, before the valley can be regained. Rising steeply out of Spiez, we thread this tunnel - the first of thirty-four on the route - and find ourselves in the narrow, wooded Emdtal, as the Kander Valley is here known. On the farther side of the valley rises the Niesen, and at Mülenen-Aeschi there may be seen the Niesen funicular railway, soaring upwards at an astonishing angle. Its steepest gradient is 68 per cent, or 1 in 1½, and it takes the traveller through a difference of level of 5,390 ft in fifty minutes, in a journey 3,850 yds in length. Cable haulage is used, with a change of carriage intermediately. The summit level of the line is 7,664 ft above sea-level.

The Kander Valley now broadens out, and our train stops at the important station of Frutigen. It is well known to winter sports enthusiasts, for here they must leave the train for the road journey to Adelboden. This latter sports centre is at the head of the valley of the Engstligenbach, which has not yet been penetrated by railway. From Frutigen, as we look up the Kander Valley, a magnificent view is revealed; huge snow-clad summits hem in the valley basin, with the Doldenhorn, the Balmhorn, and Altels prominent among them.

IN THE RUGGED LÖTSCHENTAL the Lötschberg Railway emerges from the great tunnel, the southern portal of which is seen at Goppenstein. The tunnel is over nine miles long and is bored under the main chain of the Bernese Alps.

At Frutigen the train has travelled eight and a half miles from Spiez, and has climbed just under five hundred feet without the gradient exceeding 1 in 67. But the real hard work is now to begin, and the gradient steepens to 1 in 37, which will persist over most of the next eleven miles. The observant will notice here that the method of track construction has altered. Instead of the flat-bottomed rails almost universal on Continental railways, the Lötschberg has installed on its steepest and most sharply curved sections bull-head rails with cast-iron chairs and wooden keys, after the English pattern - a tribute to the esteem in which British track is regarded as offering the maximum of security and solidity.

For some distance from Frutigen the rise in the valley-floor is but gradual. At its southern extremity, however, a rock-wall has to be surmounted to reach the upper part of the valley, in which there lies the village of Kandersteg, 1,400 ft higher in altitude. Climbing steadily at 1 in 37, therefore, the railway spans the valley by a fine eleven-arches masonry viaduct, 90 ft in height above the river and 920 ft long, to gain the mountain slopes on the east side. Shortly after leaving Kandergrund the railway and the valley floor are on fairly level terms, and it becomes clear that the railway will have to take exceptional measures to reach the desired altitude without any steepening of the ruling gradient. What has been done is soon made apparent to the traveller by the sight of masonry viaducts dotted about at various points on the steep mountain-side.

The engineer’s favourite device of spiral location has been called into play. First the railway sweeps westwards through the woods, across the full width of the valley. Doubling backwards, it regains the mountain-side, but now travelling back in the direction of Spiez, rather than forwards to Kandersteg. The backward course is continued for fully two miles, steadily rising all the time and finally entering a tunnel, 1,800 yards in length, in which a complete corkscrew turn is made. The line is thus restored to its original direction but at a far higher altitude than before.

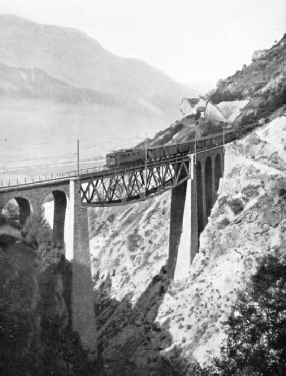

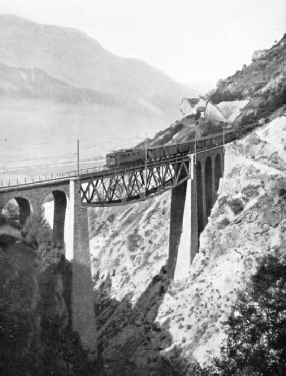

PERCHED ON A PRECIPITOUS SLOPE is Luegeikinn Viaduct. Here the line is well over 1,000 ft above the Rhone Valley, into which it descends to join the Simplon main line at Brig, about eleven miles distant.

From this upper section of the line, looking down into the woods in the middle of the valley, the traveller sees the waters of the Blausee - a little lake noted, as its name implies, tor the intense blue of its water, in whose depths may be seen petrified tree-trunks and other strange phenomena. The Blausee is reached from Blausee-Mittholz Station, on the centre section of the great double loop. Those who enter trains here must do so with caution, as, for obvious reasons, the train for Kandersteg leaves the station in the direction of Spiez, while that for Spiez has every appearance of desiring to travel to Kandersteg.

Finally we look down, from the upper level of the line, on the castle ruin of Felsenburg, alongside which we passed but a few minutes before, and which, some minutes before that, we saw from the valley-floor, high above us on the mountain-side. The Riedbach Tunnel, 1,676 yards long, carries us under the shoulder of the Birre, and incidentally serves as a protection from avalanches falling down the slopes of the mountain. We soon reach the upper basin of the Kander Valley, and the charming village of Kandersteg. As the crow flies we are but thirteen miles from Spiez, but the train has travelled nineteen and a hall miles, rising 1,800 ft on the way; yet the time allowed, including Frutigen stop, is only thirty-six minutes. Kandersteg Station is 3,870 ft above sea-level.

Justly tamed as a holiday centre, Kandersteg is attracting more holiday-makers than ever, now that the railway has made it so much more accessible than before. At the head of Öschinenbach Gorge, to the west of the main valley, there towers the magnificent shape of the Blümlisalp, with its seven snowy peaks, the highest reaching 12,040 ft. These are seen in their most impressive aspect, however, from the little Öschinen Lake, 1,400 ft above the village, into which the mountain drops precipitously, to be mirrored in its blue waters.

South of the village the mountain chain closes in as an impenetrable barrier to any further progress of the railway. These heights are scaled by the mule-track over the Gemmi Pass, which formed a highway in days gone by from the Aar Valley to the Baths of Leuk, immediately below the pass. The descent on the south side of the pass is one of the most thrilling in the Alps to the ordinary pedestrian, as it consists of a series of zigzags often resembling spiral staircase down a precipice, 1,660 ft high. The path was made jointly by the Cantons of Berne and Valais between the years 1737 and 1740. But the railway now offers the traveller to the Rhone Valley a much more comfortable and expeditious means of transit.

THE BALTSCHIEDER VIADUCT on the Lötschberg main line, illustrates the heavy cost and difficulty entailed in descending the steep mountain-side of the Rhone Valley from Hothenn to Brig; much bridging and tunnelling were necessary to make this descent. The Baltscheider Viaduct carries the rails 173 ft above a torrent, and the lattice girder span is 164 ft long.

Through a V-shaped gap in the mountain wall of the valley south of Kandersteg there pours the Kander, rushing down over a series of waterfalls, between almost perpendicular rock walls, from the Gastern Valley. The route planned for the railway took it into the mountain wall a short distance before the “Klus”, or gateway, through which comes the Kander, the intention being to bore in a straight line - which would take the tunnels under the floor of the Gastern Valley - through to the Lonza Valley, on the south side of the ridge. The railway has thus eventually to pass under the river up whose valley it has been carried from Spiez to Kandersteg. The north portal of the tunnel is a mile and a quarter from Kandersteg Station.

In railway tunnelling on such a scale as this, it is always the unexpected that happens. In this particular tunnel the unexpected and the tragic were combined in a serious accident. Boring began at either end of the tunnel, in the usual way, in October, 1906. It had proceeded about three miles from the north portal when, on July 24th, 1908, without the slightest warning, a dynamite charge burst through into a deep fissure below the floor of the Gastern Valley. The workings were immediately flooded out, and debris filled the heading for a mile back. Of the twenty-five men at work on that face only one escaped with his life; and all the valuable boring plant was irretrievably lost.

For some months the work on the tunnel was suspended. Further progress in the same direction was clearly impossible. Finally it was decided to bend the tunnel in such a way as to carry it, through hard rock for the whole distance, well to the east of the danger-point. Nearly two miles of the bore from the north portal were abandoned, and the old workings securely walled off. Both from the north and the south the boring was then curved eastwards, and the diverted centre-lines met on the last day of March, 1911. It says something for the accuracy of modern surveying and setting out that such a diversion from the straight could be made without affecting the precision with which both halves of the tunnel met in the centre, the error being only eighteen inches. A world’s record was established by driving 1,013 ft of the tunnel’s length through limestone rock in a single month. In April, 1912, the masonry lining was finished, and in mid-July, 1913, the completed tunnel, and with it the whole of the Lötschberg main line, was opened for traffic. By reason of the diversion, the length of the Lötschberg Tunnel, originally planned to be eight and five-eighths miles, was increased to nine and one-eighth miles. It is one of Switzerland’s three longest bores, the two others being the St. Gothard, nine and a quarter miles, and the Simplon, twelve and a quarter miles. Among the world’s longest tunnels, the Lötschberg takes high place.

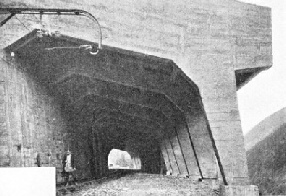

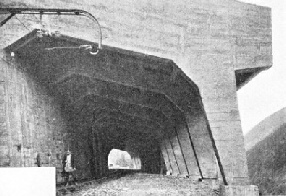

TO GUARD AGAINST AVALANCHE DANGERS in the Lonza Valley, massive galleries of reinforced concrete have been built. The sloping roofs carry the avalanches harmlessly over the railway.

The train emerges again into daylight in a wild Alpine valley at Goppenstein. Before the coming of the Lötschberg line, the Lötschental, as the valley is called, was almost inaccessible, as it could be reached only by a stiff climb up a mule track from the Rhone Valley. Now, from the railway station at Goppenstein, at which all the trains stop, it is an easy matter to penetrate one of the most primitive and unspoiled valleys in the whole of Switzerland, green with luxuriant pastures, and hemmed in by snowy mountain summits, such as those of the Bietschhorn and Petersgrat, 12,970 ft and 10,517 ft high respectively.

The highest level of the railway, 4,077 ft, has been attained in the middle of the tunnel, with the usual downward slope towards the entrances for drainage purposes. At Goppenstein the line is 4,000 ft above the sea, and now begins the steep descent of 1,765 ft to Brig, which for most of the remaining sixteen miles is inclined at 1 in 37. Crossing the valley of the Lonza, the railway takes refuge on its precipitous left flank. But so rapidly does the bottom of the valley drop away towards the Rhone Valley that the railway is soon left high up on the mountain-side. Unless suitable measures had been taken to combat the danger, the position of the line would, have exposed it to exceptional risks from avalanches.

The builders of the railway had good reason to fear the power of the avalanche. A camp for the workers on the southern half of the tunnel was established at Goppenstein, and their work was constantly impeded, in winter and spring, by great slides of ice and snow which buried the tunnel mouth.

Fighting The Avalanche

But the climax of the peril was reached on a February night, when a vast avalanche hurled itself down from the mountains above the entrance, and swept the camp completely out of existence, a number of the men losing their lives in this disaster.

For a large proportion of the three and a half miles during which the railway travels down the Lonza Valley, therefore, it has been securely roofed in. Massive galleries of masonry or concrete, with sloping roofs, have been built over the line, at every point where it crosses a recognized avalanche track, and over other stretches where snowslides are prevalent, the slope of the roofs throwing the avalanches harmlessly into the valley below. Not only so, but a great deal of work has also been done at much higher altitudes, to minimize the risk. Extending up the valley sides many hundreds of feet above the line, irregular lengths of masonry walling have been built horizontally along the precipitous slopes, after the fashion of breakwaters, to break up formation of the slides as far as possible, and so to reduce their immense force as they reach the lower levels.

The railway now passes through a curved tunnel, 1,093 yards long, and on emerging from it, the traveller in the train - who, by the way, should be careful, if he can, to get a seat on the right side of the compartment, facing the locomotive, as he leaves Spiez - is immediately confronted with one of the most wonderful sights that a Swiss railway journey can afford. He has been ushered into the Rhone Valley, spread out as a map before him, but at a level lower by more than 1,300 ft. The Rhone occupies the centre, and among the poplars which fringe its banks may be seen, with field-glasses, on the farther side, the main Simplon Railway, which the Lötschberg Railway is to join twelve miles farther up the valley. But in doing so it must descend from its airy location, high upon the mountain-side.

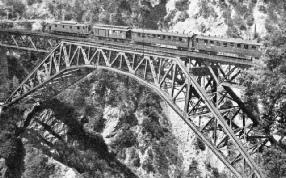

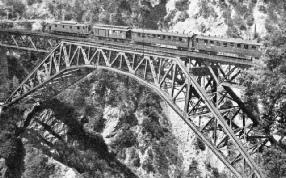

THIS MAGNIFICENT STEEL ARCH carries the Lötschberg Railway across the Bietschtal Gorge line at a height of 255 ft above the valley floor. The arch has a span of 311 ft and the 432 ft length of the bridge is flanked by tunnels on either side. Over the bridge the track has a 990 ft radius. One of the powerful Sécheron 1-C-C-1 locomotives is seen at the head of the express.

Indeed, as seen from the Simplon line, it seems almost incredible that the gash high up on the mountain flank, just to the right of the opening of the Lonza Gorge, marks the site of a main line of railway. But a Lötschberg express may suddenly appear from the tunnel at Hothenn. Few experiences can be more thrilling than to be travelling on the valley-floor in one of the Simplon expresses, while the Lötschberg train is descending from the heights, shooting over dizzy viaducts and vanishing from time to time through the tunnels which have been bored under projecting mountain spurs, until the two trains finish the contest by running neck-and-neck into Brig Station at the same moment. Both from the “high road” and from the “low road” the present writer has often witnessed this “event” in progress, and it has never failed to provide its characteristic excitement.

The Lötschberg has had much the more costly task in descending from its eyrie than has the Simplon in making its way up the wide valley. All the mountain torrents, whether from the north or from the south side of the valley, make their way into the Rhone down deep gorges. Again and again the Lötschberg line has to spring across these gorges, often on viaducts of great size. Shortly beyond Hothenn there comes Luegelkinn Viaduct, a great structure of masonry perched on what appears to be a 45-degrees mountain slope.

Impressive Viaducts

Then comes, immediately above the village of Raron, the classic bridge structure of the whole route - the mighty steel arch spanning the Bietschtal. This arch, of 311 ft span, takes a firm bearing on the rock on either side of the Bietsch gorge, and carries three lattice girder spans which have been set on a sharp curve of 990 ft radius. The level of the track above the floor of the valley is 255 ft, and the total length of the bridge is 432 ft. Another large viaduct crosses the Baltschieder Valley, partly with masonry arches and partly with one 164-ft lattice girder span, 173 ft above the torrent; this is followed by a tunnel half a mile long under one of the spurs of the Bietschhorn.

Immediately beyond this tunnel we have a magnificent view up the valley of the Visp, which here rushes down to join the Rhone. Crowning the rugged ridge which separates the two branches of the Visp - the Matter Visp, coming down from Zermatt, and the Saaser Visp, descending from the lesser-known village of Saas-Fee - we see the twin peaks of Switzerland’s highest mountain, the Dom and Taschhorn of the Mischabel group, 14,050 and 14,750 ft high. Immediately below us is the village of Visp, well known to visitors to Zermatt as the station where they change from the main-line train for the metre-gauge rack-and-pinion train of the Visp-Zermatt Railway. This line is described in the chapter on “The Glacier Express”.

And so, after having threaded twenty tunnels - four and a quarter miles of them in all - since leaving Goppenstein, and having passed over seven lofty viaducts, we reach at length the big girder span across the River Rhone. This brings us into the station at Brig, where the Italian portion of our train is marshalled on to an express that has come up the Rhone Valley from Lausanne and Montreux. From Thun the fifty-three miles journey has taken only an hour and three-quarters. But no journey of corresponding length, in any part of the world, could be packed with more of scenic thrill and variety.

A SPLENDID VIEW is provided for the traveller on emerging from a curved tunnel into the Rhone Valley at Hothenn. Here the Lötschberg Railway is 1,300 ft above the valley floor, and in twelve miles must descend to join the Simplon main line, which is travelling up the valley on the far side of the Rhone, seen as a white streak at the bottom of the valley.

You can read more on

“The Glacier Express”,

“The Great St Gothard” and

“The Simplon Tunnel”

on this website.

You can read more on

“Alpine Tunnels”

in Wonders of World Engineering