The “North Country Continental”

A Famous Train of the LNER

ONE OF THE NEW 4-

IN more respects than one the train whose running we are going to follow in this chapter is among the most interesting in the country. First of all, its working now calls for one of the longest continuous locomotive journeys performed throughout the course of the year anywhere in the British Isles. The engine attached at Ipswich, on the northbound journey, at 8.2 in the morning, runs right through to Manchester (Central) 220 miles away and reached at 2.7 p.m, and then returns the next day to Ipswich again, the one crew being responsible throughout. On this trip the enginemen encounter a combination of grading and scenery which, for one unbroken journey, is probably unique. First from the engine-

Other parts of the same train travel in various directions. A substantial section is worked northward from Lincoln to Doncaster and York, and achieves the distinction of making a return journey over a distance exceeding 400 miles daily -

After the war the main train was diverted to Liverpool, and after various rearrangements of service, too complicated to enter into here, York was once again provided with a through section over the direct route through Gainsborough and Doncaster. To this portion there is now added a through coach right up into Scotland, continuing along the East Coast route to Edinburgh and Glasgow, making a through journey of 471 miles from Harwich. The only section of the train now remaining to be mentioned is that which is detached at March on the forward journey, running from there eastward to Peterborough, and on over LMS metals to Rugby and Birmingham, 171 miles from Harwich. Between them, the various portions of this one train cover no less than 676 route miles of Great Britain daily.

As we have done on our previous journeys by boat trains we will travel towards the sea, rather than away from it, and this will mean following the various sections of the “North Country Continental” from the beginning of their journeys to Harwich. The first of these through vehicles involves us in an early start. By half-

We are in mixed company. Next to us are a couple of corridor coaches with passengers for another port -

Starting out of Queen Street terminus is no easy business The line vanishes into the black recesses of a tunnel, so that its inclination is not visible from the platform. It is actually at 1 in 42 for 1¼ miles, and for many years outward-

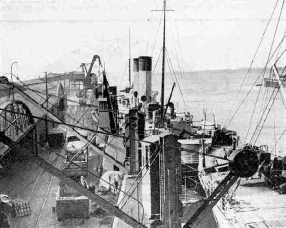

A VIEW OF PARKESTON QUAY, HARWICH. The quay is altogether 2,809 ft in length. The passenger gangway leads direct from the Station Platform to the Quay, facilitating the boarding of passengers on the Hook of Holland steamers of the LNER.

Now, by way of contrast, we have before us the most singularly level stretch of line in the whole of Scotland -

Very prominent after Linlithgow are the great tips of shale that have been left as refuse after the extraction of the valuable oil found in this neighbourhood. We are due at Haymarket at 9.42 a.m, and if we are a minute or two early, or the North train is late, quite probably we shall sweep up the four-

At 9.46 a.m. we are due in the great Waverley Station at Edinburgh. Here some busy moments await the station staff, as much marshalling has to be done round about ten o’clock in the morning. We are pushed about hither and thither, the first consideration being to get the East Coast coaches in front of us attached to the rear of the “Flying Scotsman”, due to leave at 10 a.m. In the summer months the Southampton and Harwich coaches leave Glasgow later, at 8.55 a.m, with the “Junior Scotsman”, which forms the second part of the “Flying Scotsman” proper, starting from Edinburgh at 10.15 a.m, and they run on to Newcastle in the same distinguished company.

From the middle of October, however, one “Scotsman” only suffices for the London traffic, and a special train is therefore run behind the “Scotsman”, at 10.15 a.m, to bring these vehicles down to York. One cannot help thinking that the tremendous tractive power of the LNER “Pacifies” ought to permit, at least as far as Newcastle, and except, possibly, at week-

By now it is 12.48 a.m, and as there has been no restaurant car attached as yet to our train, we shall probably be feeling the pangs of hunger. But one is waiting for us at Newcastle, and we may well rub our eyes in astonishment to see it attired in the chocolate and cream livery of the Great Western Railway! With a couple more Great Western coaches, it is provided by that company to run through to Oxford with the Southampton portion of our train; we enjoy the use of it as far as York.

Our engine from Newcastle to York is probably a 4-

At York, where we are detached from the Southampton train, there is a tedious wait of 47 minutes ere we are due to leave for Lincoln -

But now we must put the clock back for three hours in order to cross the country to Liverpool, where we find the main restaurant car portion of the “North Country Continental” waiting for us at the Central Station of the Cheshire Lines Committee. This, the largest of all the British “joint” lines, was before the grouping a combination of the Great Northern, Great Central and Midland Railways; now, of course, the companies interested are the LNE and LMS Railways. The CLC have their own coaches and wagons, but locomotive power throughout has been provided by the Great Central, and it is one of the smaller Great Central 4-

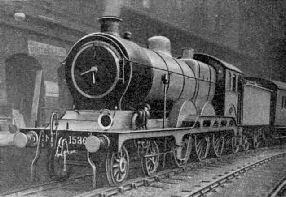

LNER (GE SECTION) 4-

The Cheshire Lines Committee have long maintained a reputation for the punctual running of the 45-

Warrington we reach at 2.28 and leave at only remaining obstacle is the ascent from Glazebrook to cross the Manchester Ship Canal at Irlam, where the line had to be raised, at the expense of the Ship Canal Company, on a gradient of 1 in 135 for two miles, sufficiently high to clear the masts of the liners passing underneath. The Partington Steel Company’s works are a very prominent object here to the right of the train, on the banks of the canal. From the viaduct down to Flixton, where the original main line of the CLC is clearly seen well below the left of the train, we probably exceed 60 miles an hour, and when finally we breast the sharp rise from Throstle Nest Junction, up over the great steel viaduct into Central Station it is to come to rest at precisely 2.50 p.m.

Here the first operation is to detach the LMS coach from the rear, or what is now to become the front, of the train, ere we see backing on what is indeed a “stranger” so far to the west of the country as this. Very spick-

Punctually to time at 3.5 p.m. we are away. The run immediately ahead of us, despite the fact that our gross load, with passengers and luggage, does not exceed 260 tons, is one of the hardest of the journey. After a swift start down to Throstle Nest, where we must slacken for the Chorlton direction, and a further slack at Chorlton Junction where we leave the Cheshire Lines for LNE metals, we have a steady ascent before us for 25 miles until we have breasted the Pennines at Dunford Bridge. You doubtless remember travelling over the same route in the opposite direction, when we tried the “3.20 down Manchester” out of Marylebone.

There are slight easings of the grade past Guide Bridge and across the viaducts at Mottram and Dinting, but after the latter, for 74 miles up through the high hills, past the picturesque chain of reservoirs which fringe the left side of the line, the line is inclined at 1 in 117 to 1 in 100. Guide Bridge must be passed at 3.22 p.m, and then only 22 min. are allowed for the 14¼ miles up to Woodhead, where we enter the famous three-

Then a swift descent past Penistone to Sheffield, with an allowance of 22 min. for the 19 miles in order to discourage excessive speed over the many sharp intermediate curves, brings us into Sheffield Victoria Station at 4.11 p.m. Here we get rid of the Cleethorpes coaches, which follow us to Retford on a subsequent train. A minute later we may see arriving on the opposite side of the station the Southampton train that convoyed our Glasgow coach as far as York. The coach in question was worked from York to Sheffield by this route for a time, joining the main train here, until the direct train from York to Lincoln was reinstated.

From Sheffield, left at 4.18 p.m. to Lincoln the 4-

MANCHESTER CENTRAL STATION, CHESHIRE LINES RAILWAY. This imposing Station covers 10 acres of ground and contains nine platforms and no less than 13 roads.

The only other engineering work of note, is the bridge crossing the River Trent at Torksey, and at 5.20 p.m. we run across a busy road level crossing -

At Lincoln we attach the North portion, which arrive five minutes earlier, and our load is thus brought up to a minimum of nine corridor coaches. We leave again at 5.32 p.m. and for many miles ahead there are no difficulties of any kind confronting the engine. The old “Great Eastern and Great Northern Joint Line” as it was before the days of grouping, cuts in a straight line across the flat Fen Country of Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire, and once we have mounted a gentle rise from Lincoln to Potterhanworth, and attained 65 miles an hour or so on the subsequent descent to Branston, speed should keep just nicely round about the “sixty” level until the next stop at Spalding.

The “North Country Continental” in the reverse direction makes a diversion from the main line to call also at Sleaford, adding thereby a couple of miles to its journey, but we take the straight line between the North and South Junctions at Sleaford and are allowed 46 minutes in which to cover the 38¼ miles from Lincoln to Spalding. A couple of minutes standing and we are away again, to make the brief run of 19 level mites from Spalding to March in 26 minutes. Just before running into March, which is reached at 6.46p.m, we pass the extensive sidings at Whitemoor, to which considerable additions, laid out on the “gravity” principle and equipped with all the latest devices for speeding up the work of marshalling, are just being made. March requires a six-

At Ely the final addition is made to our load. Just before 4 o’clock in the afternoon (at 3.55 to be precise), our two Birmingham coaches left New Street Station in that city, attached to a train of the LMS bound for Peterborough. Their initial run -

So we have now our full load. This is at the least, 11 cars, weighing probably about 340 tons, but when last I saw this train, in the height of last summer, it had 14 coaches on, mostly of the latest East Coast type stock, weighing empty 437 tons and with passengers and luggage fully 460 tons. At Ely important connections are given to Norwich, Cambridge, and the Eastern Counties generally.

We are due out of Ely at 7.22 p.m, and then follows immediately what is -

We do not pass through Newmarket, but skirt the margin of the famous “Heath” and join the Cambridge and Bury line at Snailwell Junction. On account of the slow running just mentioned it is necessary to schedule as much as 42 min. for the 28 miles from Ely to Bury St. Edmunds. Leaving the latter town at 8.6 p.m. we run eastward to Haughley, where another severe slowing is required as we join the main line from Norwich to Liverpool Street. From Haughley to Ipswich the line is downhill throughout, and with a final “burst” at 60 miles an hour, or slightly over, we thread East Suffolk Junction and run into Ipswich Station at 8.43 p.m. having covered the 26½ miles from Bury in 37 minutes. Here the locomotive that has done us such excellent service all the way from Manchester is uncoupled, and runs quietly away through the tunnel ahead of us to the engine-

AT ST MICHAEL’S we come out into the open, the loudness of the engine exhaust indicating that hard work is being put in to keep time.

For our last stage of just over 20 miles we have the services of one of the 4-

At 8.48 p.m. we enter the tunnel, take water, very likely from the track-

We are not allowed to stand at the long platform any longer than is necessary to unload passengers and luggage, as the “Esbjerg Continental” is due from Liverpool Street at 9.31 p.m, the “Hook Continental” 11 min. after that, and the “Antwerp Continental” 10 min. later still. This is one of the reasons why our timings have been on the leisurely side, as punctuality of arrival at Parkeston is of vital importance, and there is ample margin for recovery of lost time should one of our many connections put in a late appearance en route. After leaving Parkeston Quay we have but another two miles to run, calling on the way at Dovercourt Bay, ere we “make the port of Harwich” at 9.31 p.m. We have had, as I am sure you will agree, a most interesting day.

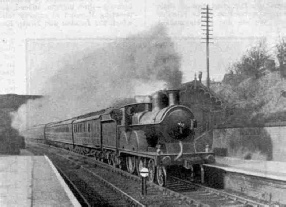

Down “North Country Continental” passing St. Michael's Station, hauled by LNER (Great Central Section) “Pollitt” 4-

You can read more on

“The Hook of Holland Boat Express” and

on this website.