Famous Viaducts

How the Railway is Carried Across River and Valley

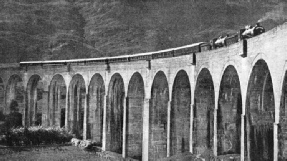

GLENFINNAN VIADUCT, in the Highlands, is a magnificent example of construction on the old North British line between Fort William and Mallaig, Inverness-

MANY people are often doubtful of the difference between a bridge and a viaduct. It is not easy to explain this; for, while all viaducts are bridges, all bridges are not viaducts. The Tay Bridge is a viaduct, while the Forth Bridge, except for its approaches, is not. A viaduct might be described as a bridge consisting of a series of relatively short spans, usually of stone or concrete, but sometimes of lattice-

The Southern Railway is notable for the several great viaducts which it possesses within reasonable distance of London. The Southern is not what one would think of as a mountainous line; the only section of it which could, by any stretch of the imagination, be described as mountainous, is the Exeter to Plymouth line, which skirts the northern side of Dartmoor. Here, as we shall see shortly, is one of the Southern’s greater viaducts. The South of England, however, is decidedly hilly, and it is in consequence of the fine wide valleys that the viaduct-

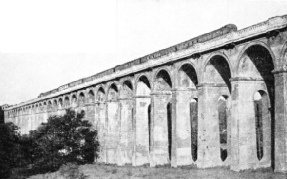

ON THE LONDON-

On the electrified main line from London to Brighton, a mile or so north of Hayward’s Heath, we find one of the finest viaducts in the British Isles. The Sussex Ouse, in this locality, is no more than a stream meandering at the foot of the broad meadows; but in the course of hundreds of thousands of years it has washed out for itself, through the Wealden clay, a valley fit to daunt the engineer of earlier days. Roughly a century ago Sir John Rennie surveyed and planned the Brighton line. It was John U. Rastrick, however, who was responsible for the design of the Ouse Valley Viaduct, and those who know it will agree that it is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful pieces of work of its kind. Built of brick and faced with grey stone, the structure contains thirty-

Another viaduct on the Brighton line worthy of notice is the Lewes Road Viaduct at Brighton, which bears away in a noble curve across the valley from the main line by Preston Park station.

Two other notable viaducts on the Southern Railway were both built by the old London and South Western Company; they differ from one another entirely, as well as from the Brighton line viaducts. One of these is the fine structure of ten arches spanning the valley on the branch between Combpyne and Lyme Regis. It is not a great viaduct, but its claim to fame lies in the fact that it was one of the very first to be built of reinforced concrete. The fact that it carries only a single track gives it a graceful and slender appearance, which it would otherwise have lost. The most unusual double arch over the deepest part of the valley consists of a masonry insertion in the main concrete span.

The other great Southern Railway viaduct is that at Meldon, between Okehampton and Bridestowe, nearly the summit level of the whole Southern system, 950 ft above the sea. This is a structure of steel similar in many ways to the American trestle bridge, and it is one of the sights of the district. The train’s passage of the viaduct reminds one of any place but the South of England; for, though the green marches of Devon and Cornwall stretch away to the north-

The heaviest locomotives on the Plymouth line, when the viaduct was built, were light 4-

But the line which stands out above all in the matter of great British viaducts is the London and North Eastern Railway. Of the companies which went to form this fine modern system, the Great Northern, the North Eastern, and the North British were all three rich in viaducts. It was the last-

The new Tay Bridge, designed by W. H. Barlow, is a much more sturdy structure, and was opened on June 13 1887. Its total length is two miles seventy-

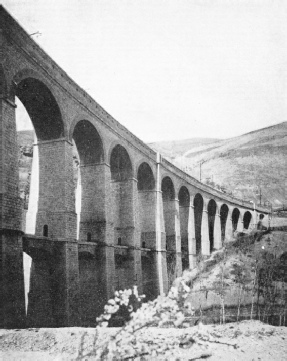

The main line of the London and North Eastern, however, meets its first viaduct long before it reaches Scotland. This is the great Digswell Viaduct near Welwyn, on the old Great Northern main line. It is built of masonry, and crosses the valley in a straight line on forty arches. On the same section is another imposing viaduct at Ilkeston; but some of the most remarkable of the LNE viaducts,after the Tay Bridge, are to be found on what used to be the North Eastern Railway. At Berwick there is the Royal Border Bridge, a grand viaduct of stone, crossing the Tweed and its valley on twenty-

SPEEDING ACROSS WELWYN VIADUCT. A London and North Eastern Railway train with a Railway Air Services aeroplane flying above. The viaduct, twenty-

There are no less than twelve fine viaducts on this relatively short line, and of these, the Belah Viaduct is undoubtedly the most noteworthy. It is an iron trestle viaduct, 1,040 ft long and 196 ft above the lowest part of the valley which it spans. The foundation stone was laid on November 25, 1857, and the whole structure was completed within the astonishing time of four months.

Before we leave the LNER we must mention, briefly, the viaducts on the West Highland Railway, which was formerly worked by the North British. The finest of these is the splendid concrete viaduct at Glenfinnan, in Inverness-

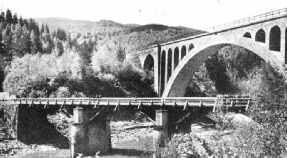

THE OLD AND THE NEW are splendidly contrasted in this picture, taken at Jaremcze, in the Polish Carpathians. In the foreground is the old viaduct, with the modern structure behind it.

Leaving the LNER in the Scottish Highlands, we can join the LMS in that locality, for the old Highland Railway, which now forms the northernmost section of the LMS, has many fine bridges and viaducts. Quite the finest is that crossing the River Nairn on the direct line from Aviemore to Inverness, which is built of Old Red Sandstone. It has twenty-

Highland Viaducts

The entire structure has a length of 1,800 ft, and the height above the river bed is 135 ft. The Highland main line abounds in fine bridges and viaducts, and another, which is well known, though relatively small, occurs in the world-

ON THE ROME-

Other notable LMS viaducts in Scotland include the Ballochmyle Viaduct in the heart of the Burns country, with its 180-

The Great Western Railway used to be especially noteworthy for the wooden viaducts designed by I. K. Brunel and built across the deep valleys of South Cornwall. After Brunel’s death in 1859, their replacement by more orthodox erections was begun, for they had their disadvantages even in those days; but the last of them -

It is in Wales that we find the best of the Great Western viaducts, and among these are the Crumlin Viaduct and the Dee Viaduct at Cefn. The Crumlin Viaduct is a trestle structure situated between Pontypool Road and Pontllanfraith. It was opened for traffic on June 1, 1857, at which time it was the largest viaduct in the world. It crosses the Ebbw Vale at a height of 200 ft, and is formed into two sections by a queer intervening hill dividing the valley. The main section, on the east side of this hill, is 1,066 ft long. The Dee Viaduct at Cefn is of stone, and contains nineteen 60-

When we reflect on the fact that Great Britain, except in the west and north, is not a mountainous country, and that even so it contains so many big viaducts, it will be realized that it is impossible to do justice to all the great viaducts of other lands, many of which are exceedingly mountainous. It will be possible, therefore, to mention only a few outstanding examples.

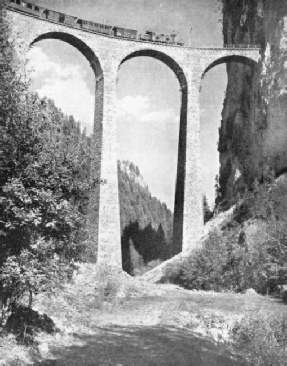

FROM THE SIDE OF A PRECIPICE the Landwasser Viaduct on the line of the Rhaetian Railways in Switzerland carries the trains 213 ft above a valley. The structure was built on a curve of 328 ft radius, and has six arches, each spanning 66 ft. The total length of the viaduct is 426 ft.

Though the Tay Bridge held pride of place among the world’s viaducts until the Lower Zambesi Bridge was built, the Stone Upper Bridge of the East Indian Railway runs it close. The frequent flooding of the rivers in India has necessitated the construction of ninety-

One of the most striking journeys in Europe for the lover of great viaducts is that provided by the narrow-

Switzerland has many notable viaducts, and here again they are remarkable for their height above the valleys they span rather than for their length. The Landwasser Viaduct, on the Rhaetian Railway, 426 ft. Long, has its central span 213 ft above the valley, while the Solis Viaduct is 292 ft above the river. Though not, strictly speaking, a viaduct, the Ponte di Melide, in the extreme south of Switzerland, should be included, since it carries trains. It is a causeway, containing a few spans to allow for the movement of the water, built across the Lake of Lugano at the foot of Monte San Salvatore. It carries the main line of the St. Gothard Railway, connecting Zurich with Milan via Chiasso. A similar causeway carries the LMS Railway’s Dornoch branch across Loch Fleet in Sutherland. This latter was built by the great Thomas Telford before the days of railways, the railway line having been added during the present century.

On the North American continent we find many splendid viaducts, one of the best known being that at Lethbridge, just under 760 miles west of Winnipeg on the Canadian Pacific Railway. It is of trestle construction, but it is built of steel instead of iron. At one point the rails are 314 ft above the river below. The trestles consist of thirty-

The United States contains two of the most extraordinary pieces of railway viaduct construction in the world. One of these is the Lucin Cut-

12,000 TONS OF STEEL went to the building of the great Lethbridge Viaduct which carries the railway across the Belly River, Alberta. The viaduct, 5,327 ft long, is supported by thirty-

You can read more on

on this website.

You can read more on

“Building the Menai Bridges” and

Wonders of World Engineering