© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

On the Footplate of a “Night Goods”

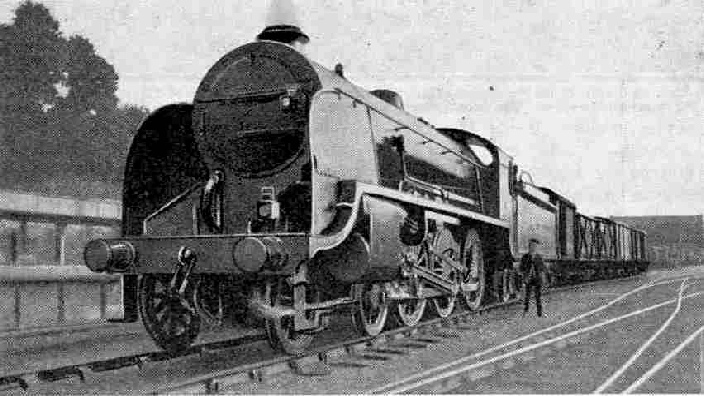

At the start of the run. The SR Locomotive “No. 826” is a mixed traffic 4-

DURING the last few years some notable speeding-

A good example of these high-

From Exeter our load was not very heavy, 16 four-

We got away in fine style, in fact the engine accelerated so rapidly down the falling gradient from Exeter that at Broad Clyst, less than five miles from the start, we were doing 65 mph with a goods train! The engine was working on 20 per cent cut off and the regulator was only two-

From the summit to our first stop at Templecombe very easy running was needed to keep time. On this stretch I was astonished at the freedom with which the engine steamed. We were maintaining an average of 40 mph over a very hilly road, and yet often we would travel for 8 or 10 miles without the fire being touched, and then only two or three shovelfuls were put on. The riding of the engine was very smooth, and even at 50 or 60 mph I was able to walk about on the footplate in comfort. So we reached Templecombe 59½ miles from Exeter in 102 minutes -

Here the load was increased to 43 vans which, with the bogie brake van, weighed about 500 tons. After a stop of 18 minutes we got away in tremendous style. On 35 per cent, cut off and the regulator nearly three-

A freight train takes a good deal more pulling than a passenger train because the friction is much greater. For an equal weight a goods train has nearly twice as many axles; the wagons do not travel so easily, they sway about, and all this increases the drag on the engine.

Once over Semley summit, the driver brought the cut off back to 20 per cent, again and the regulator was moved to about a quarter open. We kept up a steady 45 to 50 mph all the way down to Salisbury. It was now after 10 o’clock and nearly dark. In the twilight of a perfect summer evening it was most difficult to pick out the green signal lights, for they harmonised strangely with the blue-

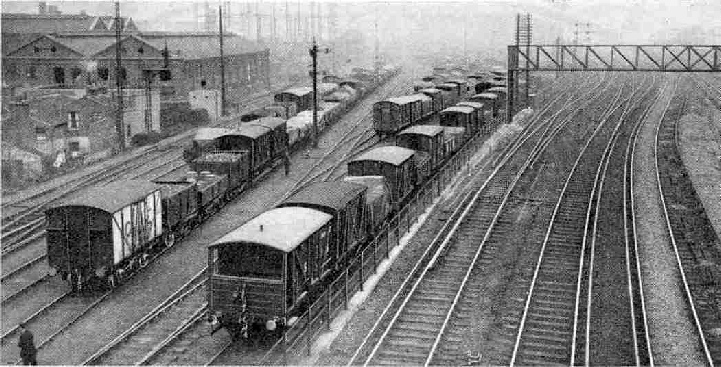

A view of part of Nine Elms Yard, where the journey described in this article terminated. This is the chief SR depot in London for freight traffic to and from the West Country.

Here “No. 826” came off and was replaced by “No. 778”, “Sir Pelleas” of the “King Arthur” class, in charge of Driver G. Gray and Fireman Barton of Nine Elms shed. The driver greeted me with: “Have you got springs in your boots?” We had not travelled far before I knew what he meant! This engine was due for the shops and was riding very roughly. Nevertheless a splendid run was made. Up the steep rise over the eastern ridge of Salisbury plain, on 30 per cent, cut off, “Sir Pelleas” gradually accelerated until we passed Grateley summit at 35 mph, 11 miles from Salisbury in 27½ minutes.

This engine, like “No. 826”, was steaming very freely. The fire-

Down the steep descent to Andover speed rose rapidly and the racket now became terrific. It was not a case of rolling or swaying, but a high-

At Worting Junction the speed was 50 mph, and three minutes later we flew through Basingstoke. To roar across the maze of points and crossings, with shunting going on on both sides of the line, and then to sweep through the big station at 55 mph, in the dead of night, was a truly thrilling experience. We were doing 60 just afterwards, and kept up an average of 46 for the next 30 miles. I had become thoroughly used to the racket by now, and the speed was most exhilarating. It was a brilliantly clear moonlight night; one could see great distances across the country, and the wooded hills around Farnborough and Pirbright looked especially lovely. After passing Woking the fire was being very gradually let down, we were nearing home.

Approaching Wimbledon, for the first time in the whole journey, we got signals badly on, in fact we were nearly stopped; but the signal cleared just in time. The fire was quite low now, and it was interesting to study the inside of the fire-

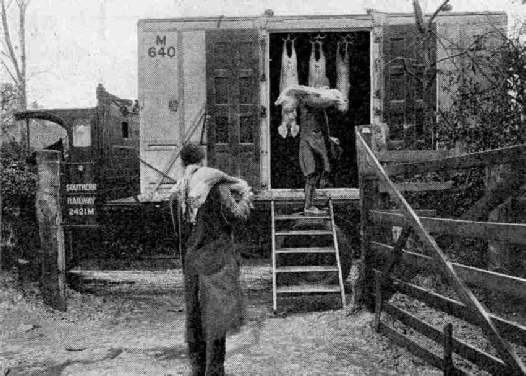

Loading meat into an SK insulated container at a West Country farm. Despatched in the afternoon, it is delivered In London early next morning.

Soon we were running through Clapham Junction, and then we were switched off the main line into Nine Elms yard. The finish was one of the strangest features of the journey. To draw up in the dark loneliness of a goods yard, with only one or two shunters with hand lamps to welcome us, seemed a curious end to a fast run compared with the animated scene on the arrival of an express at a big terminus.

In about 10 minutes a path was clear for us to back out on to the main line again. There was a short wait for the signal, and then we steamed cautiously round into Nine Elms shed and the night’s work was done. “Sir Pelleas” had run the 82 miles from Salisbury to Nine Elms in 147½ minutes, but the net time allowing for delays was only 130 minutes, an average of 38 mph.

So much for the locomotive side of the journey. In the meantime what has become of the train that we brought up from the West? This has been seized upon by the yard staff and rapidly unloaded in order to rush the meat fruit, vegetables and foodstuffs generally that composed our freight to the early morning markets. If we had had the opportunity, an exam-

Special measures are employed to ensure the swift conveyance of these miscellaneous foodstuffs to Smithfield, Covent Garden and elsewhere. Suitable containers are used in increasing numbers for perishable traffic of this nature, and fast motor vehicles await the arrival of trains at Nine Elms.

If we could follow the West Country farm produce in the final stages of this cycle of efficient transport we should find ourselves at one or other of the great London markets. Of these none is more interesting than Smithfield, the famous meat market. In addition to specially rapid transport arrangements from centres of production that are afforded by all the four group railways by way of their London goods depots, there is actually a railway station situated underground below the market.

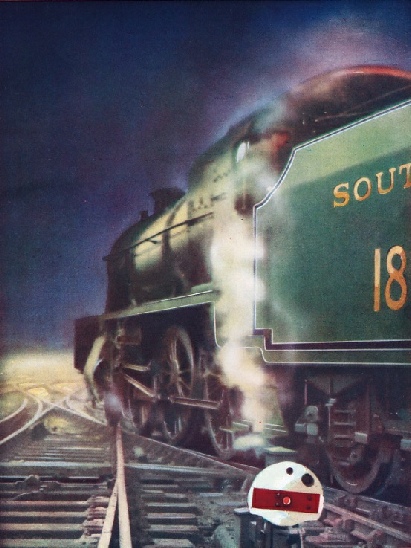

THE NIGHT JOURNEY. A mixed-

You can read more on