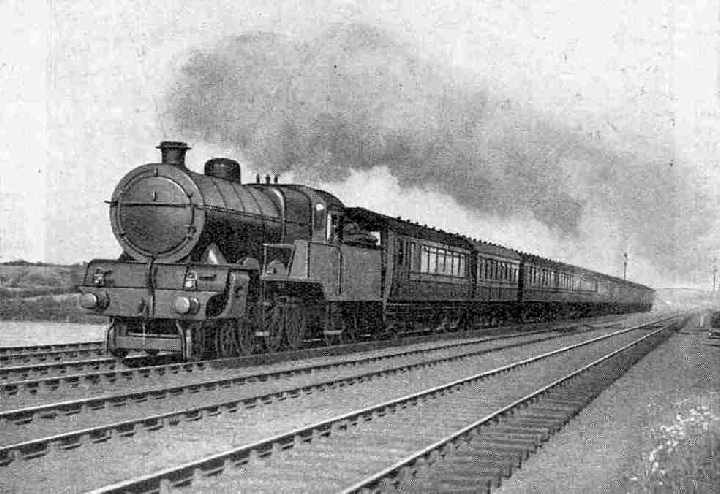

A Famous Train of the LMS

FAMOUS TRAINS - 30

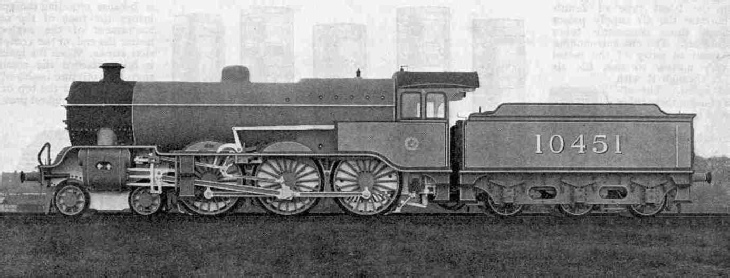

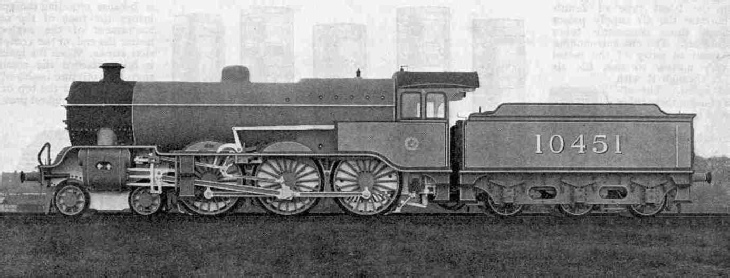

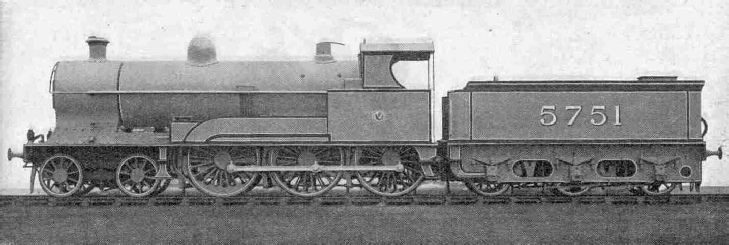

4-6-0 four-cylinder LMS Express Locomotive, Class 8.

SUCH are the modest dimensions of these islands on which we live that most of our biggest cities are within tolerably easy reach of the sea. The result is that very many commercial people take advantage of this accessibility by carrying on their business in their respective cities, but living at the seaside. This is a habit that the railway companies, not unnaturally, like to encourage, for it means a considerably longer journey, and therefore a proportionately higher season ticket rate, than if the same people were run merely to and from the city suburbs.

Thousands of London businessmen, for example, come up daily from places as far afield as Southend, Brighton, Eastbourne, Worthing, Folkestone, Margate, Ramsgate, Clacton and Walton, ranging in distance from 35 to 75 miles away, and taking in time from one to two hours on the journey in each direction. Glasgow similarly has within reach the beautiful resorts on the Firth of Clyde, and Leeds and Bradford people do not find Scarborough or Bridlington too far away. Liverpool is as nearly on the sea as makes no matter, while Birmingham, alone among the big cities, finds the sea a little too remote for residential purposes.

But it is with Manchester that we are concerned this month. The business Mancunian has a fine stretch of coast from which to choose. His favourite seaside places of residence are Blackpool, with its outlying suburbs of Lytham and St. Anne’s, and Southport. Rhyl, Colwyn Bay and Llandudno also claim their share of this daily city-coast traffic, and even Morecambe and the lakeside resort of Windermere are not too distant. The whole of this traffic is dealt with at the two adjacent stations of Victoria, once the headquarters of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway and now of the Western “B” Division of the LMS system, and Exchange, the one-time property of the late London and North Western Railway. Work is now in progress connecting the two terminals directly together, and when it is finished one of the remarkable features of the joint station will be a continuous platform of the enormous length of 2,196 ft. Woe betide the unfortunate seaside resident, in days to come, who arrives at the station at the last minute to find his coast-bound train at the opposite end of this platform from the one he expected! But we must hope that he will not do anything so foolish.

Of the two stations, Victoria is considerably the larger. Its accommodation was greatly increased early in the present century, when a new terminal portion, with 10 platforms, was added on the south side for the use of the trains to and from the Oldham, Stalybridge and Bury directions, the last-named of which are now worked electrically. There are now 17 platforms, of which 11 are terminal, and 6 are through from one end of the station to the other. A singular feature of the working is the manner in which trains to and from the east end of Exchange Station pass through the centre of Victoria, between Nos. 11 and 12 platforms, over relief tracks not provided with platforms; the same lines are used by freight trains that require to pass through Victoria.

An ingenious part of the equipment at Victoria is the overhead luggage carrier, which runs right across the station just under the roof. It is electrically worked, and the operator, who has a precarious perch below the carrier, is able, by suitable hoisting tackle, to lower his capacious luggage basket on any platform and, when it has been filled, to lift it and whisk it away to any part of the station required, without delay and with a minimum of effort.

Exchange station is on a much smaller scale and has only five platforms. It is No. 3 at Exchange, coupled with No. 11 at Victoria, that will ultimately make the 2,196 ft platform, but by means of suitable crossovers it will be able to accommodate two or three trains simultaneously. So the two stations have between them 22 platforms, and when united will make one of the largest stations in the country, though from the point of view of compactness the combination could hardly bear comparison with, say, Waterloo terminus in London.

Shortly after four o’clock in the afternoon we make our way past the Cathedral at Manchester into Exchange Station, for the departure of the first of the “club” trains. This reminds me that I have not yet explained what a “club” train is. A considerable number of years ago certain Blackpool residents formed a kind of travelling club, and requested the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway authorities to provide them with a saloon coach in which they might travel together in a comfortably “clubbable” fashion. The railway people fell in with the idea, and the “club” saloon was duly included in the formation of the chosen Manchester-bound express in the morning, and a down evening express leaving shortly after 5 p.m.

Since then on all the chief residential expresses between Manchester and Blackpool and Manchester and Southport very fine open corridor coaches have come into use, and the trains are made up thus from end to end. Thus there is not, perhaps, the same call for the club saloon as once there was, but it is still run, and the club members are assured of privacy for their journey. The same idea has been taken up since by-residents at Llandudno and at Windermere, to both of which popular resorts club saloons now run.

The actual “club” trains are the 4.30 p.m. from Exchange to Llandudno, the 5.5 p.m. from Exchange to Windermere, and the 5.10 p.m. from Victoria to Blackpool; but the 5 p.m. from Victoria to Southport and the 4.55 and 5.2 p.m. from the same station to Blackpool also have sufficient of a “club” character to be included in our survey. The collection of coast- bound expresses leaving Victoria in this 15 minutes is indeed remarkable, and still more so is the character of the passengers, as from two-thirds to four-fifths of the coaches provided on each of these trains are first-class.

The first of these expresses to be away is the 4.30 p.m. from Exchange to the North Wales coast. At one time it was timed at a rather higher speed than now, as only 48 minutes were allowed for the 40 miles between Manchester and Chester and 34 minutes for the 30 miles on to Rhyl, which, with a four-minute halt at Chester, meant 86 minutes from Manchester to Rhyl. To-day, with no stop at Chester and a one-minute-halt at Prestatyn instead, the same journey needs 90 minutes. In earlier days the departure time was 4.55 p.m, but it is now 25 minutes earlier, and an additional express leaves at 4.40 p.m. for the same direction, making calls at Warrington and Chester.

For the working of the train, which consists of 10 up-to-date bogie vehicles, amply provided with lavatory accommodation but non-corridor, the engine attached was until recently one of the handy North Western “Prince of Wales” type 4-6-0’s. Despite their moderate weight of 66 tons, apart from tender, the “Princes” have shown themselves capable of a great variety of passenger work, even up to and including fast and heavy passenger expresses, and their scope is best illustrated by the nickname “Maid-of-all-Work”. With a load of 300 tons like this, over what is throughout an easy road, our “Prince” will experience no difficulties. Lately, however, three “Claughtons” have been transferred to Llandudno Junction for the purpose of working the train.

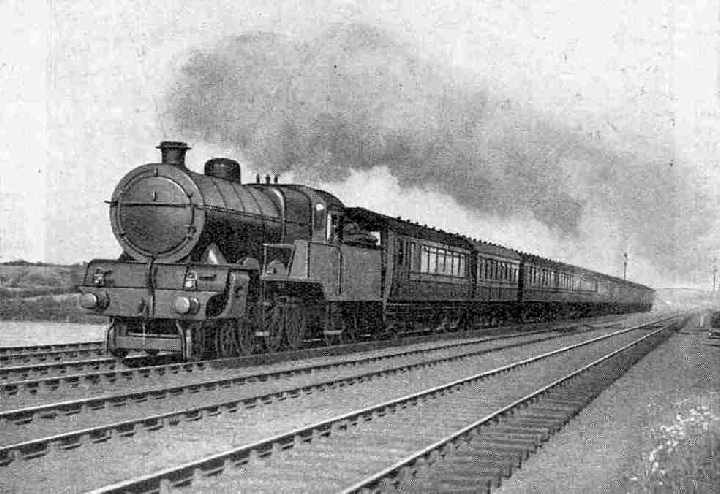

Blackpool “Club” Train.

Soon after leaving Exchange, the Llandudno “club” train passes on to the historic Liverpool and Manchester route of 1830, now all but a century old. Until we leave it, at Earlestown Junction, the line is nearly dead level, and as we are clearing the eastern suburbs of Manchester, at Patricroft, speed should be rising above the ‘‘sixty” line. For miles now we run across the bleak spaces of the famous Chat Moss, which gave George Stephenson such untold trouble in the laying of the Liverpool and Manchester line. It was only by laying great “rafts” of interwoven hurdles, brushwood and heather over the treacherous surface, and then building up his embankment on them as a foundation, that Chat Moss was conquered.

Between Kenyon junction and Newton-le-Willows we pass over the West Coast main line, here in a deep rock cutting, and brakes are immediately applied for Earlestown Junction, 16½ miles out, passed at 4.50 p.m. Here we curve off sharply to the left, in order to run down at 1 in 88 to join the main line just mentioned, at Winwick Junction. Our use of it will be brief, however, for after three miles into and through Warrington, we again diverge a mile beyond for the Chester line. In this last mile we rise sharply at 1 in 135 out of Warrington on to the fine four-track bridge that spans the Manchester Ship Canal, at a height sufficient to enable large sea-going vessels to pass underneath. One of the heavy expenses connected with the Canal was that of providing bridges the railways crossing its route, including the provision of the lengthy embankments leading up to them - one of great size at Runcorn, two at Warrington, and two for the Cheshire Lines tracks near Irlam.

From the Ship Canal bridge we diverge immediately to the left to join the old Chester route, and then begin to rise steadily. In the course of the ascent we cross over the route we have just left and continue mounting until we reach Halton Tunnel, which carries us through the crest of the ridge. Above the tunnel, which is just over a mile in length, runs the London-Liverpool main line of the LMS. From Halton the gradients are mostly falling past Frodsham. where the line is carried by a fine brick viaduct across the valley of the Weaver, and Helsby to Chester. The passage of the General Station at Chester at 5.21 p.m. is beset with sharp curves at both ends and is a slow business, but a few moments later we are gaining speed through the tunnels in “Chester Cutting”, and are doing round about 60 again as we approach Sandycroft.

Once more there is a long level stretch ahead, first by the left bank of the Dee, and then along the North Wales coast. At Shotton, by the way, there is an “exchange” station with the London and North Eastern Railway, which runs overhead. Probably few people are aware that the LNER have lines in North Wales. Originally these belonged to the Wrexham, Mold and Connah’s Quay Railway, which was absorbed by the Great Central. This little section of the LNER is completely isolated from the parent system, to which access is obtained only over the Cheshire Lines Committee’s tracks. But meanwhile we are hastening on past Flint and Holywell, and at 5.52 p.m. we reach Prestatyn, having covered the 66½ miles from Exchange in 82 minutes. Over the rest of the journey we have no time to dwell. Stops are made at Rhyl, Abergele, Colwyn Bay and Llandudno Junction, and by 6.43 p.m. the Llandudno “club” train it, at rest in Llandudno, 87¾ miles from Manchester.

Well before this time the Blackpool and Southport “club ” trains have finished their shorter journeys. Of these the 4.55 p.m. is usually the lightest, eight corridor coaches, two of which are destined for Fleetwood, sufficing for the greater part of the year. The engine we shall probably find to be one of the fine Horwich-built four-cylinder 4-6-0’s of “Class 8”, many of which work on these coast services. For an engine of such power, a train of some 215 tare tons - with passengers not more than 230 tons or so - is but a featherweight, despite the difficult character of the journey. By comparison with the journey just mentioned, this one includes a number of very heavy gradients, as well as severe speed restrictions at various points.

Over the extraordinarily sinuous section of line from Manchester through Salford to the “Windsor Bridge No. 3” Junction at Pendleton we gain speed, in preparation for the stiff climb past the station bearing the singular name of “Irlams-o’-th’-Height”, up to Pendlebury. This is for two miles at 1 in 99, and will bring down our speed to about 30 or 35 m.p.h. After this there follow some sharp undulations, notably a steeply-graded dip on to the troughs at Walkden, and 2 miles of falling grades also to Atherton, at between 1 in 232 and 106; but of these, owing to constant trouble with subsidences caused by colliery workings underneath, our driver is unable to take full advantage. Then comes a bad slack for the junction at Dobb’s Brow, where we leave the Liverpool line and turn northward. This first 12 miles has occupied 19 minutes.

We are now running over a short spur line that carries us across to the Preston line proper, from which we diverged at Pendleton. It is presumably to ease the congestion of the latter route, which has but two tracks, that the majority of the Blackpool expresses are booked to take the much harder four-track route through Atherton. The Hilton House spur, which is tremendously steep, rising for 1½ miles at between 1 in 51 and 74, and for another three-quarter mile at 1 in 204, avoids Bolton, and brings us back to the Preston line at Blackrod, whence we run on through Chorley to a junction with the West Coast main line at Euxton, After slackening severely here, to 25 m.p.h, a few more miles of downhill running prepare us for the even worse slowing through Preston, which we pass at 20 m.p.h. in 44 minutes from leaving Victoria, 29¾ miles distant.

After the steep pull out of Preston the difficulties of our engine are at an end, as there is little in the way of grades from there on to Blackpool. After eight miles of four-track line, over which a further set of track-troughs, near Salwick, enables our engine to pick up an additional supply of water, we approach Kirkham Junction at high speed.

From here three routes are available to Blackpool, and it is interesting to note that all three are used in succession by the 4.55, 5.2 and 5.10 p.m. trains. We are to curve to the right, taking the northernmost, to the Talbot Road Station, on the north side of Blackpool. The 5.2 will take the central route, direct to Waterloo Road and from there into the Central Station. This is both the shortest in distance and the most recent in construction, but as it serves Blackpool only, and none of the outlying towns, its use (with the exception of this 5.2 p.m. express) is confined to special and excursion trains. Then comes the 5.10 p.m, which follows the southernmost route into Blackpool, curving round in a great loop to reach Lytham, Ansdell and St. Anne’s on the way to Waterloo Road and Central Station.

For the 14½& miles from Preston to Poulton the 4.55 p.m. express is allowed 17 min, and we make our first stop, 44¼ miles from Manchester, 61 minutes after starting. Here the two through coaches for Fleetwood are detached from the rear, and with six coaches left we pass on to Bispham, where a brief stop is made, and Talbot Road, arriving at 6.6 p.m. We have covered a total distance of 47¼ miles, and the comparative slowness of the running must be put down to the difficulties of the route.

Platform 12, Manchester Victoria Station.

Between the 4.55 and 5.2 Blackpool expresses there comes the 5 p.m. Southport express. This is a considerably heavier train, the winter formation amounting to 11 open corridor coaches, often expanded in summer to 12 or 13. This also is usually a “Class 8” 4-6-0 turn, but I was greatly astonished to see the train go out of Victoria the other day with a Midland 4-4-0 compound in charge. Over such gradients as those between Manchester and Wigan, this 300-ton train is a tremendous load for a compound, and I should dearly have liked to see how the engine fared on Pendlebury bank, but unfortunately time did not permit.

The Southport express follows close on the heels - or, I suppose I ought to say, the wheels - of the 4.55 to Blackpool, passing Dobb’s Brow Junction five minutes later, at 5.19 p.m; but no reduction of speed is needed here, as the Southport train takes the straight line on to Hindley, where it diverges from the Liverpool line to the left to get through Wigan. The passage through Wigan, which is approached by extremely sharp curves, must not be made at more than 30 m.p.h. and, with such a load as this, 27 minutes from Manchester proves to be none too great an allowance for the distance of only 16¼ miles. Rising grades follow to Gathurst, but after that all is plain sailing, and there is a fine straight stretch across the level marches of West Lancashire slightly in favour of the engine, which enables a speed of over 60 an hour to be maintained for some miles, especially if any time has been lost on the congested and difficult earlier stages of the run. St. Luke’s, 32½ miles from Manchester, is reached in 47 minutes, and the main station at Chapel Street, ¾-mile further, at 5.51 p.m.

We now have to follow the fortunes of the 5.2 and 5.10 p.m. Blackpool trains. The former has an eight-coach formation of the very latest LMS open corridor stock, and is generally hauled by a 4-4-0 Midland compound. To save clashing with the Southport train, it is taken over the right hand, or “fast” lines from Victoria to Windsor Bridge No. 3 Junction, and from there over the old main line to Preston via Bolton. This is a mile further than the Atherton route, but the gradients are much easier, the average of the rise from Pendleton to Bolton being about 1 in 200. The chief obstacle is the long and severe slowing through Bolton, to 20 m.p.h. The timing is very easy, however, 20 minutes being allowed to clear Bolton, 10¾ miles; 47 minutes to Preston, 30¾ miles; 71 minutes to the stop at Waterloo Road and 76 minutes to Blackpool Central.

The 5.10 p.m. - the real Blackpool “club” train - is another of heavy formation, being generally made up to 10 corridor cars and the club saloon, but expanding to 13 vehicles in the summer season. This is an almost invariable “Class 8” 4-6-0 turn of duty. Following the Southport express to Dobb’s Brow Junction, which is passed at 5.30 p.m, the 5.10 carries on over the very steep Hilton House spur, pursuing the same route as the 4.55 p.m. coast bound train to Blackrod, Chorley, Preston and Kirkham. Preston is passed at 5.57 p.m, Kirkham at 6.9 p.m; and the first stop is made at Lytham, 43½ miles from Victoria, at 6.17 p.m. Like all the Blackpool and Southport trains, this express has been decelerated from its earlier running times. At one period Lytham was reached in the even hour from Manchester, but the much heavier corridor rolling stock now in use, with its more limited seating accommodation in proportion to weight, is doubtless in part responsible. After making stops at Ansdell, St. Anne’s and Waterloo Road, the “club” train rolls into Blackpool Central at 6.40 p.m, exactly 90 minutes after starting, having covered a total distance of 51 miles.

There is now but one “club” train left to mention - the Windermere express leaving Exchange at 5.5 p.m. This express completes one of four leaving Exchange and Victoria in the 10 minutes between 4.55 and 5.5 p.m, all running to or through Preston and each one getting there by a different route. The 4.55 p.m. out of Victoria goes by Atherton, as we have seen, and the 5.2 by Bolton; the 5 p.m. Glasgow express out of Exchange takes the longest route - 33 miles - through Eccles, Tyldesley and Wigan (North Western), where it is combined with the second part of the 1.30 p.m. “ Mid-day Scot" out of Euston; while our 5.5 p.m. to Windermere, in order to get in front of the Glasgow train, takes the “Lancashire Union” line from Bickershaw to Standish, over a route which it is one of the only two passenger trains in the day to patronise, through Whelley. Another most singular fact is that this last route involves the use of over half-a-mile of London and North Eastern metals, between Strangeways East and Amberswood East junctions. How many readers of the I wonder, know that it is possible to travel over the LNER on the way from Manchester to Windermere?

The Windermere train provides a very easy locomotive working. It is usually entrusted to a Midland compound, but occasionally to a 4-6-0 “Prince”. Four non-corridor coaches make up the formation, with the “club” saloon on the rear. The route followed is slack-infested and very heavily graded throughout to Preston, the worst pitch being at 1 in 67 up near Whelley. The 32½ miles to Preston require an allowance of 55 minutes, the Windermere train arriving just two minutes after the 5.10 p.m. Blackpool “club” train has passed through. At Preston, through Liverpool coaches are added, and after a halt of five minutes, a level run follows over the 21 miles to Lancaster, allowed 26 minutes. A brief sight of the sea is obtained at Hest Bank, and then the Windermere “club” train carries on through the important junctions of Carnforth and Oxenholme without stopping, making Kendal, 21¼ miles from Lancaster, half-an-hour later. It is just 2¼ hours after leaving Manchester Exchange that the train puts in an appearance at Windermere, having travelled 83 miles. In the opposite direction it makes a faster trip, cutting off the odd quarter, and completing its journey from Windermere to Manchester in two hours.

One point that cannot fail to be noted in connection with the trains whose working is described in this article is the amazing complexity of the London, Midland and Scottish system in Lancashire. We have just seen how four expresses leave two adjacent Manchester stations for Preston within 10 minutes of each other, each one following a different course. The 5 p.m. Southport express and the 5 o’clock from Exchange to Glasgow, again, often run for considerable distances in sight of one another on their journey to or through the two neighbouring stations at Wigan. It must be remembered, however, that this complexity arises partly from the fact that two systems once independent have now been amalgamated. As is the case in many other parts of the country, had the grouping of the railways taken place at an earlier date, it is probable that many such routes, built purely for competitive purposes, would never have come into being. The money thus spent could often have been put to far better use in the doubling and improvement of previously existing lines. But these unnecessarily ramified tracks, all of which have to be staffed and maintained, constitute not the least of the problems which our great railways have to face, in their struggle towards more economical working. Possibly the necessity for strict economy in railway working may eventually lead to some of the alternative routes being closed.

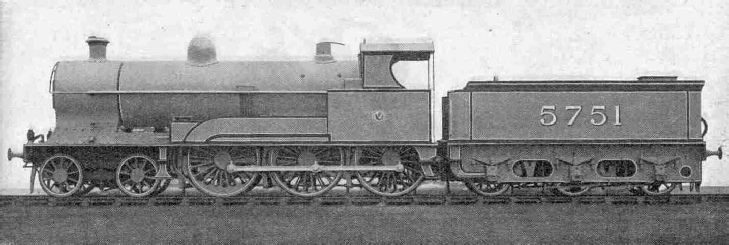

4-6-0 LMS Express Locomotive, “Prince of Wales” Class.

You can read more on “The Midland Scotsman”, “The Royal Scot” and “The Story of the LMS” on this website.