© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

Three Joint Railways

Combined Enterprises in the East, North-

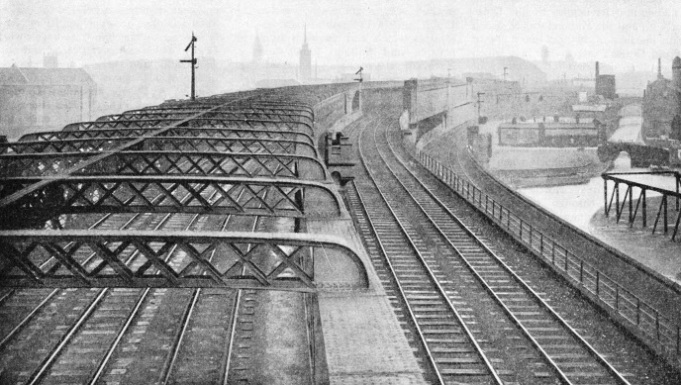

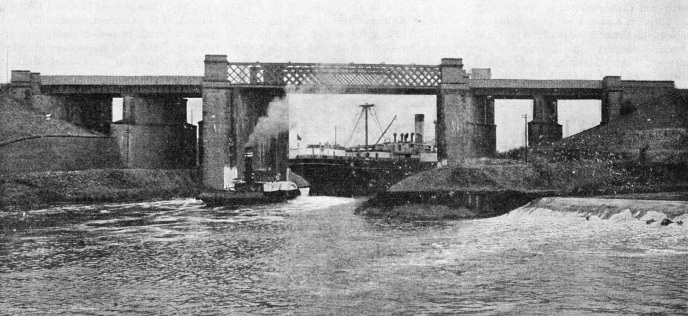

THE CHESHIRE LINES are a system jointly owned by the LMS and the LNER. The joint railway was originally incorporated in 1885. This photograph shows the high viaduct by which the Cheshire Lines tracks enter Manchester Central Station. The joint railway has 143 miles of standard gauge track open, and handles some important main-

.

CAREFUL study of a railway map of England will reveal the fact that, in addition to the four great companies, there are three other main-

These are the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway, the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway, and the Cheshire Lines. The first and last named are jointly owned by the LMS and the LNER, the Somerset and Dorset is jointly owned by the LMS and the Southern. Each railway is under the administration of a Managing Committee formed from the chief officers of the owning companies.

The Midland and Great Northern owes its name to the two older companies which owned it before they became merged into the LMS and the LNER respectively; but it was not always a joint railway. More than one company owned and worked the lines which have since come under its joint Managing Committee, and the system as a whole has had a decidedly chequered history. Of the old lines, the Eastern and Midlands was the most important. This company had its headquarters at King’s Lynn, or, as it is more commonly called, Lynn, in Norfolk, and was in its turn an amalgamation of two still older companies, the Yarmouth and North Norfolk and the Lynn and Fakenham. The amalgamation took place in 1883, ten years before the present Joint Committee took over control. The other constituent companies were the Bourne and Lynn Railway and the Peterborough, Lynn, and Sutton Bridge Railway.

The oldest section of the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway is the Spalding-

This Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway is in a peculiar position. The Midland and Great Northern is already joint between the LNER and LMS, but the Norfolk and Suffolk is in its turn owned by the LNER and the bigger joint company. It has two lines, the one already mentioned running from Yarmouth to Lowestoft Central along the coast by Gorleston and Hopton, and another connecting North Walsham with Cromer (Beach) via Mundesley-

This extraordinary example of “joint-

Cromer Beach Station is served by the lines of the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway. This Railway, the oldest section of which dates back to 1858, is now owned by the LMS and LNER and comprises some 183 miles of track.

The Great Eastern’s rival had to travel a longer way round by Peterborough, but the route had various advantages. Not the least of these was the standard of comfort, for the Great Northern provided the rolling stock on the through trains, and this was superior as a rule to the standard Great Eastern coaches of the period. Although checkmated in the matter of a Norfolk monopoly, the Great Eastern still managed to gather a few crumbs by the construction of the Norfolk and Suffolk Joint lines, which it owned jointly with the Midland and Great Northern. Thus did the Great Eastern make a little out of the Midland and Great Northern Joint traffic to and from Lowestoft and Mundesley. Now that the Great Eastern and the Great Northern are both merged in the LNER, the position is that the LNER has the lion’s share of any receipts which may come in from the Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway. Naturally the grouping of the railways caused competitive working from King’s Cross and Liverpool Street respectively to lose its object, and the service via Peterborough is now treated simply as an alternative.

Across the Fens

The main line of the Midland and Great Northern may be taken as that beginning at a point near Little Bytham (Lincs), where it is connected with the LMS branch from Saxby. It crosses the LNER and runs via Bourne, Sutton Bridge, South Lynn, Fakenham, and Melton Constable, to Cromer. This line carries the express trains from the Midlands to the East Coast. A triangular junction provides access to Spalding. At Sutton Bridge the main line is joined by the line from Peterborough and Wisbech. on which run the through trains from King’s Cross to Cromer. From South Lynn a short branch, two miles long, runs north to King’s Lynn.

The country traversed by these initial sections is flat in the extreme, for they pass through the heart of the almost weirdly desolate Fens. Naturally engineering features are not spectacular, for the Fen Country is the last place to require imposing viaducts or long tunnels. There is only one tunnel, a short one near Bourne. A little to the east of Sutton Bridge, however, the River Nene is crossed by the fine Crosskeys Swing Bridge, which carries both road and railway traffic, and there is another swing bridge over Breydon Water, near Yarmouth. At Bourne, too, there is a most unusual feature. The Old Red House, an Elizabethan mansion, was once the residence of Sir Everard Digby, involved in the Gunpowder Plot. It is incorporated in Bourne Station. No other Elizabethan railway station can be traced.

At King’s Lynn, as on the old Eastern and Midlands Railway, are situated the head offices of the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway. These are in the town, instead of being at King’s Lynn or South Lynn stations, as might be expected. The M & GN trains use the same station at King’s Lynn as those of the LNER, but the South Lynn Station is independent, and has extensive sidings and a locomotive running shed adjoining.

It is a rather remarkable fact also, apart from the unusual situation of the offices, that these are not even situated in a town on the main line of the railway which they control, since King’s Lynn, as already stated, is two miles from the main line of the M & GN.

After Lynn the Fen Country is left behind, and the scenery becomes gently hilly, increasing in contour as the line bears eastwards through Massingham and Fakenham to Melton Constable. Melton Constable is an important junction, and here also are the Mechanical and Civil Engineering Departments’ workshops and offices, where all engineering repair work and much constructional work is carried out. The village of Melton Constable is some way from the works.

From Melton two branches bear away from the main line, one running north-

The old railways which went to make up the M & GN had an extraordinary collection of locomotives, and some which were bought second-

Midland Influence

As evidence of the success of these Eastern and Midland engines, during this century the M & GN built several 4-

After the present Joint Committee had taken over, many new locomotives were built. From first to last, with two important exceptions, the designs of the true M & GN locomotive classes have originated at the old Midland works at Derby. During the 1890’s, numerous handsome 4-

Although the rebuilding process has changed their outlines, their Midland origin is still unmistakable to anyone who knows the present Midland Division of the LMS. Contemporaneously with these, a batch of 0-

The first of the important exceptions to the Midland rule originated at Doncaster, and consists of a series of heavy 0-

The locomotives of the Midland and Great Northern, about fifty in number, are painted a dark chocolate colour, lined out with bright yellow. Until quite recently, however, a striking livery was in use, namely, deep gamboge yellow, somewhat resembling that used by the Brighton line in days gone by. The coaching stock on the Midland and Great Northern is of the same type as that used by the LNER for secondary and country branch passenger traffic, together with some of the older North Western bogie carriages. They include several early corridor coaches which were formerly used on the East Coast Anglo-

For a cross-

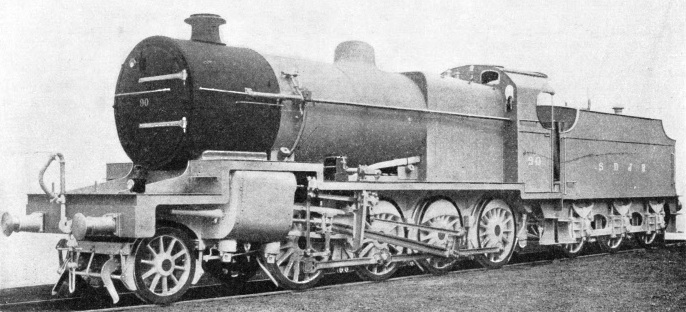

2-

We will now turn from the Fens and the hill pastures of East Anglia to the richer and more luxuriant localities of the West Country, where we find the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway linking Bath with Bournemouth.

Link With the Broad Gauge

In some ways, the Somerset and Dorset bears a strong resemblance to the M & GN, and it, too, was not always a joint railway. Though the Somerset and Dorset has had a chequered past, it has been notable for its steady improvement under the joint administration of the Midland and the London and South Western and their successors, the LMS and the Southern Railways. For some years it had the most comfortable third-

The Somerset and Dorset’s history began with the incorporation of two separate railways, the Somerset Central, a broad-

The two railways were gradually extended to link up with each other. The Somerset Central laid down a third rail to accommodate through trains from the Dorset Central. When finally, in 1862, they amalgamated, the gauge was made uniform throughout. In 1874 the Somerset and Dorset was connected with the Midland by a line from Evercreech Junction to Bath. In 1876 the Midland and the London and South Western took a joint lease of the line, and its hard times were over.

The old company continued to exist until the grouping in 1923, when it was dissolved, and the Somerset and Dorset became a joint undertaking of the LMS and the Southern, as successors to the Midland and the London and South Western. The Somerset and Dorset must not be confused with another railway which was absorbed by the Great Western in 1923 -

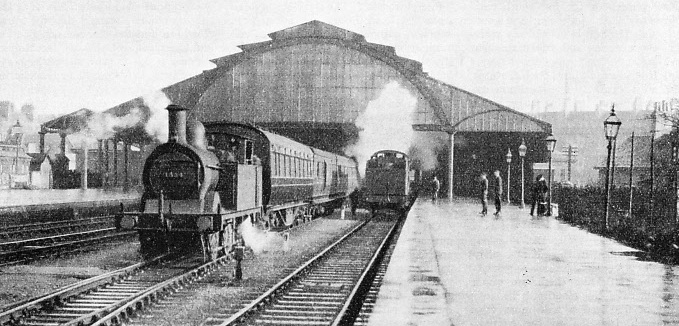

QUEEN SQUARE BATH. From this station the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway operates trains to Bournemouth West, a distance of 71½ miles, via Evercreech Junction and Templecombe. Queen Square, which is the terminus of the LMS line to Mangotsfield Junction, for Gloucester and Birmingham, is about one mile from the Great Western Railway’s station at Bath.

To return to the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway, the LMS influence is, perhaps, stronger than on the Midland and Great Northern Joint. The locomotives are provided by the LMS, though until the end of 1929 the Locomotive Department was in much the same position as that of the Midland and Great Northern Joint.

The plan of the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway is simple in the extreme, the lines appearing on a railway map in the form of the letter Y. The main line runs north-

These main and branch lines comprise the whole system, which consists of 105½ miles of route, all but a little over forty-

The original locomotives of the Somerset and Dorset, before it became a joint railway, were, as with those of the M & GN, somewhat heterogeneous. The ordinary passenger trains -

Powerful 2-

These engines were painted dark green, but on the Wells branch there was an exception. This was a 2-

With the coming of the Joint Committee in the 1870’s, greatly improved locomotives and rolling stock made their appear-

With certain exceptions, the 4-

On January 1, 1930, the LMS took over all the Somerset and Dorset Joint locomotives, while the carriages and wagons were divided between the LMS and the Southern Railway. To-

Few railways besides the Somerset and Dorset can boast of traversing such charming country throughout practically the whole of their systems. Sylvan and pastoral beauty follows the line-

On the Bath line there are severe gradients over the Mendip Hills. An ascent of five and a half miles from Evercreech Junction to the summit-

Throughout its length from Bath to Bournemouth, the Somerset and Dorset line is traversed by the well-

The Night Express

On Friday nights and Saturday mornings in the summer there is also an excellent night express, which arrives at Bourne-

IRLAM VIADUCT, 8½ miles from Manchester, carries the track of the Cheshire lines over the Manchester Ship Canal.

The busiest of the three joint mainline railways is the system known as the Cheshire Lines, worked by a Managing Committee with headquarters at Liverpool, and jointly owned by the LMS and the LNER, the latter company’s share being the larger. This railway was originally incorporated in 1865 as a concern jointly owned by the Great Northern and the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railways, the Midland coming in as a third partner shortly afterwards, in 1866. The Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway later became the Great Central, which, with the Great Northern, became a constituent company of the London and North Eastern. This is the reason why LNER interests predominate in the Cheshire Lines of 1935.

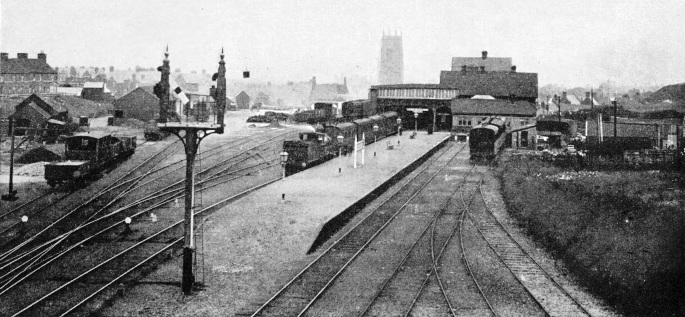

MANCHESTER CENTRAL STATION, a terminus of the Cheshire Lines. This important station, with nine platforms, has to accommodate a large volume of passenger traffic from Liverpool and Cheshire, London and the Midlands. A goods yard and station adjoin the passenger station.

A closely associated neighbour of the Cheshire Lines is the Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway, which was incorporated as far back as 1845. It is similarly jointly owned by the LMS and the LNER and, though only a little over nine miles in length, carries a heavy passenger traffic. It was electrified in 1931, being the first passenger-

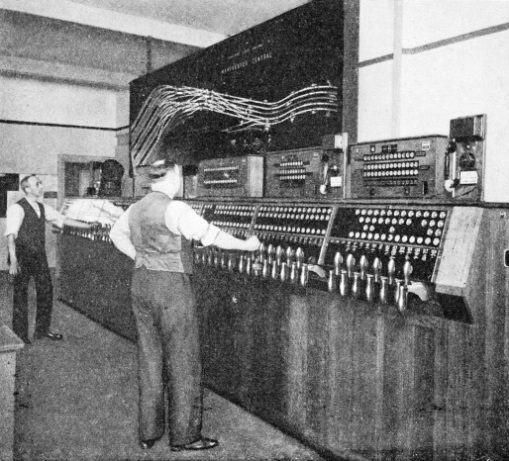

POWER SIGNALLING was introduced in June 1935 at the Manchester terminus of the Cheshire Lines Committee. The electrically operated signal box, seen on the right of this photograph, replaced four mechanical signal boxes. All the signals controlled by the new cabin are of the colour-

The total length of the Cheshire Lines, roughly 143 miles, is less than that of the Midland and Great Northern, but the system and traffic are much more concentrated. It connects Manchester Central with Liverpool Central Stations by means of a main line running through Glazebrook and Warrington, to the south of the historic line of the LMS. From Halewood, on the main line, a branch runs north to Southport (Lord Street Station); from Glazebrook another runs east to Stockport and Godley Junction on the Sheffield-

Manchester Central Station, with its great arched roof reminiscent of St. Pancras in London, is the largest station on the Cheshire Lines; it covers ten acres of land practically in the heart of the city, and contains nine platforms with a total length of 6,000 ft. Trains from the Great Central section of the LNER run into London Road Station as well as the Central, but nearly all the Midland Division traffic from the LMS is handled by the Cheshire Lines. At Liverpool Central Station, the Cheshire Lines deal with all the LNER traffic into Liverpool as well as with their own. This terminus adjoins that of the underground electric Mersey Railway, giving rapid access to the Docks and to Birkenhead.

THE INTERIOR OF THE POWER SIGNAL BOX which controls Manchester Central Station, its approaches, and entrances to goods yard. The operating room of the signal cabin contains an electric interlocking frame of 128 levers. A white indication light is provided for each lever, and this is illuminated when the lever may be pulled and extinguished when the lever is locked.

You can read more on “Britain's Inland System”, “Cross Country Routes”, “The Pines Express”, “The Romance of the LNER”, and “The Story of the Southern” on this website.