© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Grand Trunk Railway

The romantic story of this important railway system

RAILWAYS OF THE COMMONWEALTH -

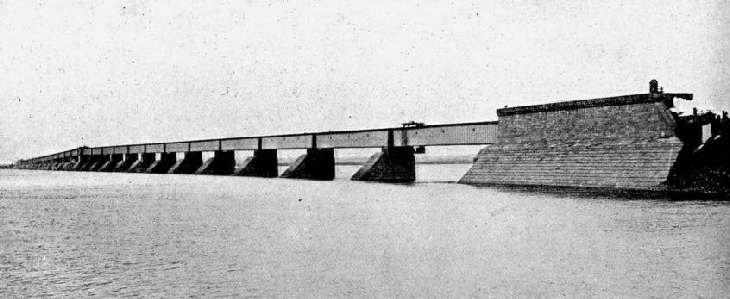

THE “EIGHTH WONDER OF THE WORLD”. The Victoria Tubular Bridge, built by Ross and Stephenson, across the St. Lawrence River, to carry the Grand Trunk Railway from bank to bank.

THE fifties of the nineteenth century constituted a busy epoch in the development of the railway. British engineers and railway builders were in urgent request the whole world over to plot and lay the highway of steel. In 1850 only fourteen countries were blessed with these transportation facilities, ranging from a handful of 15 miles in Switzerland to 6,621 miles in Great Britain and 9,021 miles in the United States. Not a mile of metal had been laid in South or Central America, south-

About this time a large firm of British contractors, Peto, Brassey, and Betts, having completed some big undertakings on the European continent, aspired for new worlds to conquer by railway. They had an immense and valuable plant lying idle with which they could start operatic anywhere without delay. Moreover, the possession of this complete equipment enabled them to tender for work at favourably competitive figure, inasmuch it was more expensive to let it lie idle than to use it.

This situation developed just when group of daring financiers had decided upon the railway invasion of British North America. The latter considered this territory to offer tempting attractions, despite the fact that at that date the population of the country was only about 3,100,000 scattered along the shores of the Atlantic, the River St. Lawrence as far as Ontario, and the narrow strip on the Pacific coast known as British Columbia. Some 66 miles of line met the whole requirements of the country, but it was considered adequate, because the population depended upon the water arteries for the movement of traffic.

The first attempt to provide Canada with railway facilities was unpretentious in the extreme. It was a wooden tramway extending a distance of 17.38 miles between La Prairie, opposite Montreal, and St. Johns, on the Richelieu River, so as to offer combined railway and water connection via the Hudson River, Lake Champlain, and Richelieu River with New York. This line was opened for traffic with much jubilation in 1832. But the first winter played such havoc that the wooden rails were torn up during the ensuing spring and replaced by metals. This humble beginning was on a parallel with the famous Stockton and Darlington Railway, the engines and rolling stock being of the most primitive description.

The British financiers evolved an ambitious undertaking, and appeared to have an open field. But conflicting interests soon arose. In 1845 a corporation secured the right to and did build a line from the port of Portland, Maine, to the international boundary, near Norton Mills, Vermont. However, directly it was completed it was taken over by the British financiers for a period of years, and continued from the frontier to Longeuil, on the south bank of the St. Lawrence, near Montreal.

The activity of the British interests prompted other enterprises in different parts of the country with an utter lack of cohesion. Odd lengths of line were built here and there. Realising the drawbacks incidental to this sporadic policy, the British financiers gathered up the isolated sections, and consolidated them into a homogeneous whole, at the same time under-

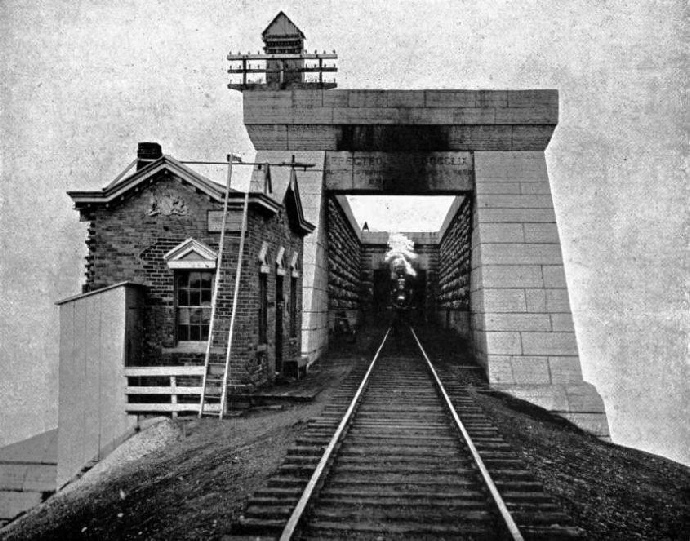

TRAIN EMERGING FROM THE OLD TUBULAR BRIDGE. It carried only a single line.

The railway builders had not been on the ground long when they found that they had under-

The severe winter, with its marrow-

Faced by such pluck-

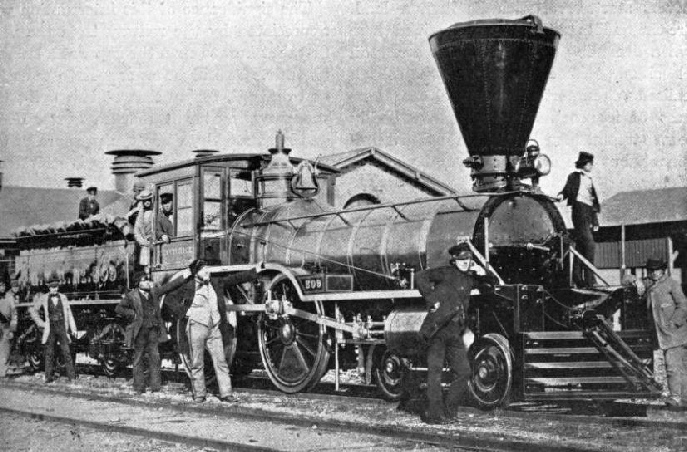

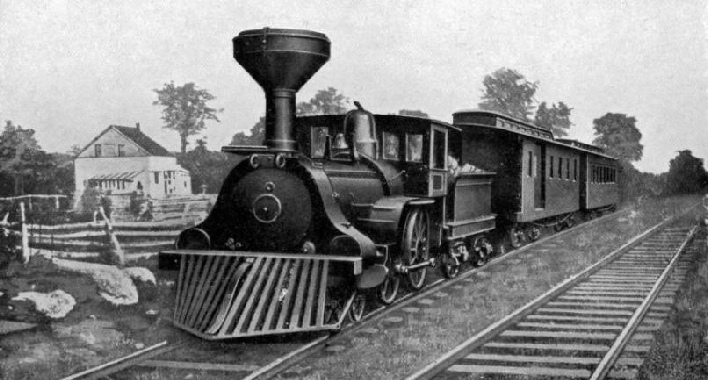

THE “TREVITHICK”, A FAMOUS FOUR WHEEL COUPLED FLYER OF ITS DAY. Wood was used as fuel, which was stacked in the tender. Note the funnel-

Yet, despite all difficulties, the pioneers prosecuted their task with commendable vigour. The labour problem was acute, but was overcome by attracting workers from the homeland, who, after they had completed their grading work, bought and settled farms with their accumulated wages, and soon attained a position of complete independence if not wealth. Thus the railway builders accomplished two ends by a single stroke. They not only opened the country; they settled it as well. Con-

When at last the railway was completed between Montreal and the Lakes, through communication with the Atlantic sea-

The greatest drawback, however, was experienced every spring and autumn. The ice-

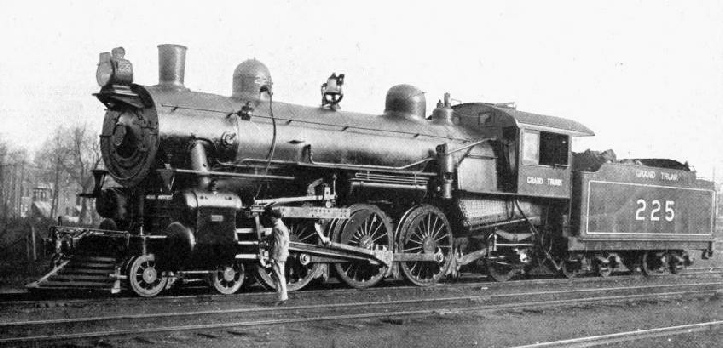

THE HUGE “PACIFIC” WHICH HAULS THE “INTERNATIONAL LIMITED” TO-

The significance of this interruption was appreciated by the railway from the very first, but how to span the gap was a baffling obstacle. A bridge was certain to be costly and difficult, seeing that at this point the waterway is over a mile in width, deep, and runs swiftly, while the pressure of the vast ice-

It was feared that no creation would be able to stand. However, Mr. Alexander Ross, an accomplished engineer, who had achieved a big reputation building railways in Europe, took up the problem. He proposed a massive bridge, built upon the tubular system, such as carries the London and North Western Railway across the Menai Straits to-

THE VICTORIA JUBILEE BRIDGE, MONTREAL, SHOWING THE NEW SUPERSTRUCTURE. It was built around the tubular bridge, so that traffic was not stopped. The present bridge carries a double track, electric tramway, roads, and pavements.

The first stone was laid on July 22nd, 1854, and Ross haunted the scene day and night until the bridge was completed on November 24th, 1859. Surprises were sprung upon him and his collaborators at every turn, but every difficulty was subjugated as it developed, and with very little delay to the work. No chances were taken. The piers were built upon ample lines, and carried well down into the river bed to withstand a current of some 7 miles per hour and the terrifying ice-

The setting of the iron-

The Victoria Tubular Bridge, as it was called, was reckoned to be the “Eighth Wonder of the World”. So soundly was it built that it defied the caprices of the St. Lawrence for nearly forty years. It was a huge metal bore carrying a single track, and as the railway business grew it became taxed anti taxed until it carried 100 trains a day. The working of the bridge was brought to its limit; not another train a day could be squeezed in. Only one train could be on the bridge at a time, and this bottle-

CANADA’S CRACK TRAIN, “THE INTERNATIONAL LIMITED”, making 60 miles an hour between Montreal and Chicago. The 842 miles are covered in 22 hours, including stops.

Accordingly, in the early ‘nineties, the question arose as to whether the time had not arrived when the Ross and Stephenson bridge should be superseded by a structure more in accordance with the times. The point was: “What is the most economical means to achieve the desired end?” The subject was discussed earnestly; finally it was decided that the easiest, simplest, and cheapest means of meeting the situation was to provide a new superstructure, making the conversion upon piecemeal lines under traffic conditions. The piers were enlarged so as to take a new and wider open bridge to accommodate two sets of metals, a road for trams as well as highways for vehicular and pedestrian traffic.

The piers were examined and found to have been built so strongly that they required no additional reinforcing; the new masonry to carry the widening merely was added to the old. Work was commenced in October, 1897. Each new span was built around the existing tube, and when completed and ready for setting in position, the old span was cut away from its supports and then withdrawn. Work went forward uninterruptedly, span by span, although for two months not a stroke could be done owing to the severity of the winter of 1897-

The new bridge is more than twice the weight of its predecessor, containing 22,000 tons of steel. It is 66 feet 8 inches in width, and varies from 40 to 60 feet in height, while it cost £400,000. The present linking communication, known as the Victoria Jubilee Bridge, with its double track, is likely to meet all requirements of the railway for many years to come, its capacity being practically unlimited in conjunction with the electric block system, permitting some three trains to be on each road of the bridge simultaneously.

PULLMAN DRAWING-

When the British builders laid the original stretch of railway, constituting the foundation of the Grand Trunk system, the broad gauge of 5 feet 6 inches was adopted. But later railways in other parts of the Eastern provinces preferred the Stephenson gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches. Canada accordingly had its “Battle the Gauges”, even as did Great Britain. Sir Henry Tyler, when he assumed the presidential chair of the undertaking, recommended in 1867 that the 5 feet 6 inch should be adopted as the standard for the Grand Trunk, and that a purchased subsidiary stretch of 60 miles, running from Detroit to Port Huron, which had be built on the narrower, should be converted to the broader, gauge. However, the Stephenson gauge triumphed on the North American continent, so that, unlike the Great Western Railway at home, the Grand Trunk bowed to the inevitable without delay. In 1874 the broad gauge was abandoned in favour of that of 4 feet 8½ inches.

While Sir Henry Tyler manifested short sightedness in respect of the gauge, he was exceptionally perspicacious in another respect. Chicago at that time was healthy growing town of 200,00 people. Tyler advocated pushing the Grand Trunk metals into the budding metropolis of the Middle West with all possible speed. The movement was opposed, but he gained the day, and the rails were carried into Chicago.

This was a smart display of enterprise, as subsequent events have proved conclusively, because the steel highway between Montreal and the “Windy City” constitutes the busiest railway artery in Canada, over which flows the commerce of two powerful nations. The growth of Montreal as a shipping point during the summer is developing this traffic in an amazing manner, as Chicago and its flourishing industrial environs arc provided with an additional outlet to Europe.

The original highway between these two points was a single track, which, comparatively speaking, was laid as cheaply as possible, making curves to avoid obstacles, and with heavy banks which, as traffic grew, hindered easy, cheap, and quick

movement severely. For some years the company tolerated these drawbacks, with the result that it was outstripped by more energetic rivals which had arisen; indeed, its very existence was threatened. The railway became a by-

COMBINED PULLMAN AND SLEEPER.

The lower berths are made up between each facing pair of seats. The upper berths are let down like shelves from the angle ceiling.

At this juncture energetic spirits secured the reins of control, and the process of rejuvenation was undertaken regardless of expense. The whole of the trunk road between Montreal and Chicago was torn up, straightened, flattened, and many superfluous miles were cut out. Moreover, it was double-

The result of this wise move was felt instantly. Traffic congestion was removed, and the commercial centres in the Middle West, obtaining quicker dispatch, embraced this route for their shipments. Passenger traffic advanced likewise by leaps and bounds, and as this became more and more imposing no effort was spared to foster it. This policy culminated in the introduction of the “International Limited”, which to-

While overhauling was in progress the railway also pursued the wise action of buying out rivals. Odd short lengths of line here and there were acquired and consolidated into the parent system. Thus some of the most relentless competition was eliminated, and a huge system, now aggregating 5,300 miles, forming a gigantic steel web over the whole of Southern Ontario has been spun.

CARILLON AND GRANVILLE RAILWAY TRAIN. The oldest train in America, with the old famous “Birkenhead” locomotive.

[From Parts 11-

You can read more on “The Conquest of Canada”, “The Doorway to Canada” and “The International Limited” on this website.